It’s a hot night in 1977 at bj’s Show Bar in downtown Vancouver. The staff and performers are doing a “turnabout”: the waiters and bartenders are up on stage performing, and the performers are serving drinks.

A young woman named Crema gets on stage for the first time ever and wows the crowd with her performance as the Sweet Transvestite from the Rocky Horror Picture Show.

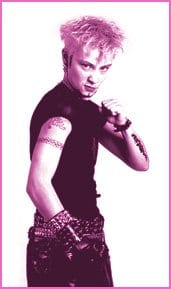

Twenty-seven years later, Rayne, “a bigendered dyke who’s on the butchy side,” paints himself silver and puts on a killer performance as Marilyn Manson.

Both Crema and Rayne are part of Vancouver’s rich drag king history, and part of the queer community’s lively ongoing discussion about what it means to do drag.

Vancouver kings have opposing views on a number of issues. The biggest differences relate to how they define drag, and how they understand the connection between their performances on stage and their own gender identity.

After her performance as the Sweet Transvestite-“a woman impersonating a man who was dressed as a woman”-Crema went on to become a popular novelty act among the drag queens at BJ’s and elsewhere around town. She still performs occasionally, particularly at fundraisers for favourite causes.

For Crema, there is a clear division between her stage persona and her everyday identity. The way she sees it, drag is most of all about performance.

“When I do Tom Jones I put on my sideburns and my suit and then I take it all off after the show. I don’t dress like that offstage.”

It’s not drag, she says, if “what you wear onstage is no different from what you wear on the street.”

When asked whether doing drag is related to her sense of her own gender, Crema confidently says no. “It’s not a question for me. For me it was a performance. I’m a woman and I don’t have a question about it.”

KC Pearcey put on monthly drag king shows at the Lotus from 1996 to 1998. She echoes Crema on the importance of performance.

“It’s just lip-synching,” Pearcey says, “so you have to put a lot into it.”

Pearcey also agrees with Crema that drag and gender identity are different, though she sees them as related.

The mid-’90s, when Pearcey was performing, were a time when a number of people were coming out as trans. Some people had expectations that the shows at the Lotus would be a platform for trans issues or that Pearcey would be a spokesperson for the trans community. “I am trans myself,” Pearcey notes, “but drag’s not about gender. It’s about performance.”

When asked whether a female-to-male trans person is doing drag when he performs onstage dressed as a man, Pearcey pauses to consider.

“When I dress up like a man it doesn’t feel like drag. But it’s the audience perception-I’ve always been perceived as a dyke, as a woman.”

So would she call herself a drag king? “Yes, why not?” But there is a line, says Pearcey, where drag and trans identity collide.

“In my opinion, if you are transitioning and you’ve gone through the process [hormones and surgery] and you’re calling yourself a man, you’re not a drag king. Drag to me is you’re dressing in a costume that’s the opposite of what you’re perceived as or how you identify. I didn’t come to the show to see you being you.”

Other drag kings say that for them, their drag personas and gender identities are more closely entwined.

Mr Bec was one of the most popular and successful performers at Pearcey’s shows. Bec says she never fit into the idea of “girl sexy.”

Drag was a place where she could explore different aspects of her gender and find acceptance and even applause.

“I’m naturally more butch-I couldn’t put on heels and a dress and feel sexy, but I felt hot doing drag,” she says.

She rarely performs now, but remembers performing as a fun and empowering experience. “Mr Bec was a character, an extension of a part of me. The swagger, the ego, the confidence-‘I got my silicone dick strapped on and I can do it right now!'”

For Devin, 2003’s drag king of the year and co-producer of the now-defunct Kings of Vancouver, drag performance and gender identity are even more closely connected.

“Drag for me is about performing my gender,” Devin says. “Performing my gender on stage creates a space for myself and other people that don’t identify with the binary gender system.”

Rayne is the reigning Drag King of Vancouver and co-hosts Club 23 West’s monthly drag contest, put on in part by Suzan Krieger (who used to do drag with Crema in the early ’80s as part of the Quadra Players).

Rayne has developed his ideas about drag and gender identity through focussed research: reading, talking to other kings and, most recently, travelling to Chicago last October for the annual International Drag King Extravaganza (IDKE).

Rayne identifies as bigendered not transgendered (“I have my girl days and my boy days”), and uses the male pronoun when speaking as Rayne, his drag king persona.

“First I was unclear about the relationship between transgender and drag,” Rayne begins. “People were not supportive of transgender or bio males doing drag. But I think transgender people are more than welcome.”

At IDKE, Rayne saw a biological man performing as Austin Powers. Rayne believes that this was definitely a drag king performance. “He’s a drag king because his performance is nothing like him. He wears a costume, puts on a performance, wows the crowd. The crowd is saying, ‘hmmm, is that really a guy?'”

Rayne is perhaps best known for his performance as Marilyn Manson. “I’m fairly butch by nature and I was painted silver head to toe and I was wearing really tight pants. I actually felt like a drag queen.”

Drag kings hold a wide range of opinions on what drag is and how it relates to their own gender, depending on who they are and when they began performing-performers didn’t even begin using the term “drag king” until the early ’90s.

But there’s one thing they all seem to agree on: “It’s a rush,” says Crema. “You want to vomit before you go on stage-then it’s a rush and then it’s over. You do it for the fun.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra