Authorities in Vancouver and Toronto are clamping down on vendors of the party pill PureRush following the Jun 30 death of a 55-year-old man. The man, who has not been identified by police, consumed PureRush and later collapsed during a Toronto Pride wrap-up party at the Guvernment nightclub. Police have confirmed that the man had a preexisting heart condition.

Adam Wookey, manager of the Toronto head shop Purepillz, says he’s had visits from police in connection with the shop’s sale of the PureRush pills, which contain benzylpiperazine (BZP).

“We’ve also had visits from Health Canada regulators, asking questions and telling us to shut down,” says Wookey.

On Jul 10 the federal health authority released a statement warning the public that Purepillz is selling “unauthorized” substances that pose “serious health risks” and announced it was reviewing whether BZP and a derivative, 3-trifluoromethylphenyl- piperazine (3-TMFPP), should be listed under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.

“Both BZP and 3-TMFPP are unauthorized drugs and there is no approved medical use for these drugs or known industrial use for BZP in Canada,” states Health Canada spokesperson Paul Duchesne via email. No one from the Toronto Police Service responded to requests for comment by press time.

Wookey says that, while the drug can be dangerous if used improperly, by offering an alternative to the black market the shop is providing a harm-reduction service similar to safe injection sites and methadone clinics.

“We produce drugs that fill the same needs as things like methamphetamine and MDMA [ecstasy] — a high to get you through the night,” says Wookey. “Except with us you know what you’re getting and you’re told how to use it properly.”

Matt Bowden, president of the New Zealand-based company Stargate International which makes PureRush, agrees, arguing that BZP-containing party pills should be regulated as a recreational substance in Canada.

“There are legal drugs available that can be dangerous so [governments] provide risk- management strategies around their use,” says Bowden. “We want to do the same thing around party pills as with alcohol.”

Bowden points to New Zealand’s policy of regulating BZP rather than prohibiting it as a way to control potential risks.

BZP, synthetically derived from black pepper, was developed by a British company in the 1940s as an antiparasitic for livestock. Bowden says he became aware of the substance after reading circa-1970 drug trials examining BZP’s potential as an antidepressant.

“[Researchers] found it had a similar effect to amphetamines at about one-tenth the potency,” says Bowden, who subsequently used BZP’s ambiguous legal status in New Zealand to market it as a legal substitute for ecstasy and crystal meth.

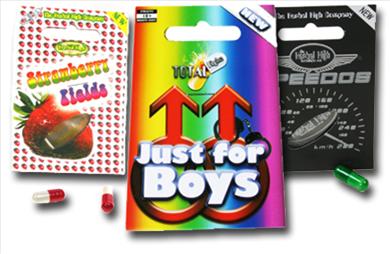

Bowden says that in New Zealand ravers have flocked to BZP since it mimicks the euphoric feelings of their favourite party drugs and until recently could be bought hassle-free just about anywhere. Manufacturers and vendors liked that BZP could be produced cheaply and began flooding the market with brands like Charge, Kandi and Red Hearts.

By 2005 one in five New Zealanders between the ages of 13 and 49 and almost half of 18- to 29-year-olds had tried BZP at least once, according to a national survey conducted by Massey University. In 2004 New Zealand’s drug-monitoring body, the Expert Advisory Committee of Drugs (EACD), estimated that the country of four million consumed up to two million blister packs of the drug — market value $25 million — annually.

EACD stopped short of calling for a BZP ban, concluding the drug’s side effects were mostly mild and that buying party pills in-store undercut the black market.

“Substitution of illicits with piperazines is occurring, mostly among users who are afraid of the damage to their lives that a conviction would bring and who also wish to normalize the transaction required to purchase their choice of recreational substance,” the committee noted in its 2004 report.

In 2005 New Zealand’s government created a new category of restricted drugs to accommodate BZP, allowing the ministry of health control over age-of-sale restrictions, quality control standards and labelling requirements.

Wookey says he follows similar standards at his Toronto store, checking for ID and warning users not to mix BZP with other drugs or alcohol or take it if they have a preexisting health condition.

“Not everyone’s going to follow the directions,” he says, “but if you’re here and we’re telling you ‘don’t mix this with alcohol and don’t mix this with drugs,’ it’s a better education than you’ll get buying drugs off the street corner.”

Purepillz customer Jase, who asked that his last name not be published, says he and his friends feel more comfortable buying from Purepillz — which at least attempts to offer safe usage guidelines — than “taking their chances” on street drugs. The gay Torontonian says he takes BZP to relieve his migraines and for its ecstasy-like “calming effect.”

“I take it now for the migraines but I also like the buzz,” says the 27-year-old. “If you take it in a social setting it gives you more of a euphoric feeling but if you’re just sitting at home it can be very relaxing.”

He adds that he has an addictive personality and would therefore have second thoughts about taking it if he found it dangerous or habit-forming.

***

Data out of New Zealand suggests that, as far as party drugs go, BZP might be the lesser evil: 45 percent of illicit drug users in the Massey survey claimed they prefer BZP “so they do not have to use illegal drugs” and only 2.2 percent of users met the criteria for dependency, based on amphetamine addiction standards. Despite an estimated national consumption of 200,000 party pills per month a 2007 study by Auckland City Hospital, home to the country’s largest emergency clinic, found only 26 of 4,122 overdose patients were admitted in connection to BZP use over the preceding two years, and that of those most suffered from anxiety, palpitations, nausea and vomiting. In 21 of those cases BZP had been mixed with another drug. There were 2,349 reported alcohol overdoses at the hospital during the same period.

However Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) psychopharmacology specialist and University of Toronto pharmacy professor Wende Wood says that until BZP is clinically tested Purepillz customers are taking a risk.

“Unclassified means just that: We don’t know enough,” says Wood. “To have something approved for consumption you have to prove it’s safe for the majority of users.”

Wood points out that BZP has never been tested for adverse reactions in humans under controlled conditions nor have long-term effects of taking the drug been established. She says that other stimulants in the same class of drugs put stress on the heart and have been known to cause fatality long after an individual has stopped taking them.

“Anything that is in the stimulant class can kill someone,” Wood says. “People can and do overdose on caffeine pills. These aren’t the kinds of drugs you want to be taking lightly.”

Despite Wookey’s emphasis on education there is evidence people misuse BZP. Three in 10 respondents in the Massey survey said they’d used BZP to enhance the effects of illicit drugs rather than replace them, which Wookey says can be dangerous. No surprise then that as of 2007 the two recorded overdose deaths worldwide (US and Switzerland) where BZP was a factor involved individuals who had also consumed alcohol or drugs such as ecstasy.

A five-month study at New Zealand’s Christchurch Hospital in 2005 also reported more than a dozen patients suffered toxic seizures after taking bootleg BZP several times more potent than the government-regulated variety. The incident, along with an election year full of war-on-drugs rhetoric, led New Zealand to institute a ban on BZP possession in April of this year.

Bowden argues that regulators should have cracked down on rogue manufacturers instead and predicts the BZP market in New Zealand will now go underground — just like the illicit drugs it was originally meant to keep people away from.

“Politicians can pass a law telling apples to go jump back up into trees but they won’t be able to change gravity,” he says. “In the same way you can’t legislate an end to the supply of drugs because the demand is there. Currently that demand is entirely satisfied by the black market.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra