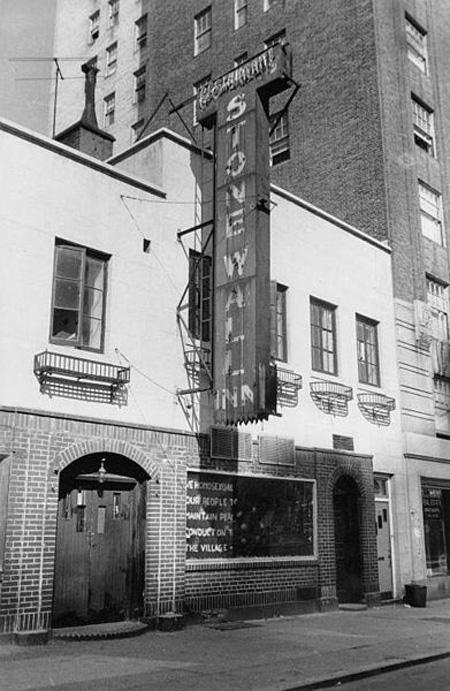

It was a just another hot, sticky night toward the end of June. The streets of Greenwich Village were filled with cruising men, displaced street youth, drug dealers and random musicians trying to make a few bucks from small audiences. But when New York City’s finest raided the Stonewall Inn in the early hours of June 28, something extraordinary happened.

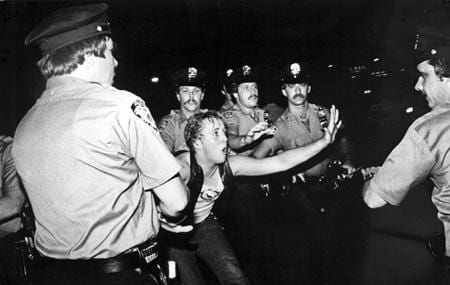

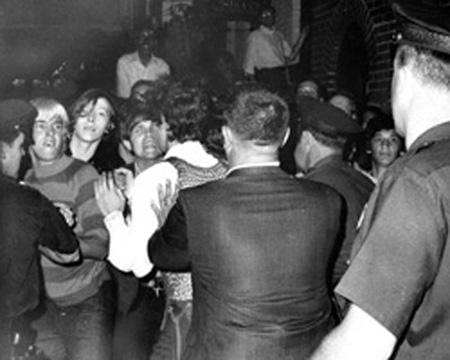

Police raids on the city’s gay bars took place all the time, but that night was different. That night people fought back. They were angry. Maybe it was because gay icon Judy Garland had died two days earlier, or because the heat got to everyone. Or it just might have been that gays couldn’t take it any longer. But that evening, and for the next two evenings, Christopher St was filled with gays, as well as the neighbourhood’s more motley denizens, heckling, taunting and at times engaging in physical exchanges with the police. It was the birth of a new era of queer life. But exactly what that new era was is up for debate.

Stonewall, or rather the myth of Stonewall, has become an intrinsic part of our history. It is a milestone and a touchstone of gay freedom and revolution, but it has also become a millstone weighing us down with its historical burden. Have we, as a community, given such incredible weight to Stonewall, turning it into a sentimental story of singular self-assertion, that we have distorted what it actually means, or might mean?

Maybe if we really understood the complexity of Stonewall – rethink it in the tangled web of late-1960s history from which it has too often been removed – we could see it for exactly what it was and better understand our relationship to it.

My own connection to Stonewall is complicated. At the time I was a 20-year-old college student across the river in Newark, New Jersey. On the big night I was probably in New York for a hamburger and a double feature of art films. The following day I heard about the first riot but figured that it was a one-shot deal and never thought that the energy would be sustained – albeit greatly abated – over two more nights. But even then the event didn’t seem like front-page news, and nobody called it a riot; it was slightly more than a minor skirmish with the police, the sort of thing that happened all the time on the hot city streets.

Although within weeks of the event I would become very involved in the new gay liberation movement, Stonewall did not mean much to me at the time. Nor, I must say, does it mean a whole lot to me now. At Dartmouth College in March of 2009 – where I teach courses that include Introduction to Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies – I found myself spending an entire class trying to get students to attach less importance to the Stonewall riots and to see them in perspective.

It’s not so easy. Some students think Stonewall was simply the first gay pride parade, with floats and an afterparty. (I’m not sure why they think the word “riot” is included.) Others imagine full-scale street fighting, and once a student asked me how many gay people died at the Stonewall Inn. Their more informed classmates understand the relatively small scale of the event but presume that its reverberations were felt immediately – the high-pitched scream heard around the world.

To understand Stonewall we need to place those valiant acts of street power and street theatre into a larger historical perspective. The first fact I impress upon my students is that for almost 20 years before Stonewall the country saw the growth of a vibrant homophile movement. The Mattachine Society, founded by Harry Hay in 1950, was the first gay rights organization in the US. It was followed five years later by the lesbian Daughters of Bilitis, founded by Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon. The Society of Individual Rights was founded in San Francisco in 1964, and the North American Conference of Homophile Organizations came into being in 1966.

These groups completely changed the public discourse about homosexuality across the entire country. Without these homophile groups, nothing that happened in 1969 and the years afterward would have been possible. In praising Stonewall, as we do now, we all too often completely erase the profoundly important work that these groups did for nearly two decades. Stonewall was, in a very real sense, both a continuation of this work as well as a radical break from it, as it brought the very idea of homosexuality from the realm of the private into the public world of the street and used anger, not reason, as its impetus.

The second thing I try to impress on my students is that without the prevalence of the Vietnam War protests, without the women’s liberation movement, without the example of the Black Panthers, the Young Lords and the counterculture’s mantra of “sex, drugs and rock and roll,” there would have been no Stonewall riots. There would have been no gay liberation movement (at least not as it happened in 1969.) The queens – and let’s remember that they were aided by the street people in the Village, men and women we would now call homeless – rioted at Stonewall because everybody was rioting; they protested because everyone was protesting. The Stonewall riots were completely in sync with the crazy, frantic, angry and yes, sometimes heedless political activities – including the bombings by anti-war groups like the Weather Underground, as we were reminded of so frequently during this past election – of the late 1960s.

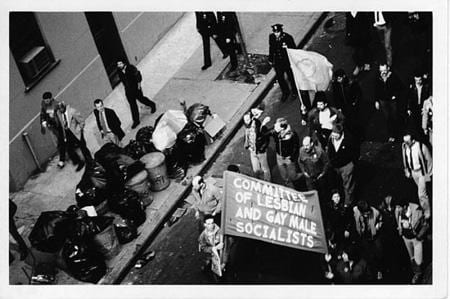

The gay liberation movement was not made up of non-profit groups raising funds and lobbying to enact laws. It was a grassroots movement, a groundswell of women and men who had reached the breaking point. The first major gay activist group to form after Stonewall was the Gay Liberation Front – a name borrowed from the Woman’s Liberation Front, which in turn borrowed it from the Vietnamese National Liberation Front, which claimed the spirit and moniker of the Algerian National Liberation Front, which fought French domination in Northern Africa. The phrase “Gay is good” was derived from “Black is beautiful.” Gay power emerged naturally from black power.

It wasn’t that we were copying other movements but that we saw ourselves as part of a broader struggle. Gay liberation was possible because the whole culture was being transformed and transfigured. Considering the enormous changes that took place as a result of these movements, it truly was the second American Revolution. There was a decisive break, and afterward things were different for gays, women, people of colour and young people. It may not look like that now – or at least not all the time – but America changed in those years, and all for the better.

But even as I write this I feel that there are details missing. While all of these connections are true – even as they are forgotten in most remembrances of Stonewall – they lack concrete details and feel like radical rhetoric. So let’s look at exactly what was going on during the five years before Stonewall that, along with the important work the homophile movement had done, set the stage for this remarkable event. As Bob Dylan sang in 1964, “The times they are a-changin’,’ and when we look back at the massive cultural and political changes that were occurring, it is impossible to imagine that Stonewall wasn’t inevitable.

In March of 1964, César Chávez and the grape pickers’ union called for the first nationwide boycott of California grapes, while at the same time the University of California Berkeley closed its campus in response to students demanding their right to speak out against the war in Vietnam. Later that month, the Supreme Court granted married couples the right to birth control. In response to an increasingly angry civil rights movement, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act in June. Even with this minor commitment to justice, the next year ushered in a wave of violence.

In February of 1965, Malcolm X was assassinated, and while Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, guaranteeing federal protection for voter registration, August saw the first truly serious race riots in Los Angeles, in which almost 1,000 buildings in the Watts neighbourhood were looted, burned or destroyed. As if the world wasn’t mad enough, Harvard professor Timothy Leary urged Americans to “turn on, tune in, drop out” – the drug revolution hit the streets.

In 1966, race riots destroyed large sections of Chicago and three African-American teenagers were killed by National Guard troops. Things got only worse in 1967 as full-scale riots in Detroit and Newark, as well as serious conflicts in 33 other cities, left 66 people dead and 10,000 more homeless. Antiwar protests escalated as the US sent nearly half a million soldiers to Vietnam, many of them African-American men from the inner cities. On the domestic front, CBS ran a groundbreaking news show called The Homosexuals, which was the first time self-identified gays talked about their lives on television. In November, the Oscar Wilde Bookshop opened on Mercer St in Greenwich Village – the first gay bookstore in the world.

In April of 1968, the assassination of Martin Luther King led to riots across the country that left 39 people dead and thousands of others hurt. Robert Kennedy was assassinated two months later. In the midst of this, gays became more visible when Mart Crowley’s groundbreaking play The Boys in the Band opened on Broadway. Women’s liberation became increasingly visible when feminists staged a mass demonstration at the Miss America pageant in September. In the midst of this upheaval it made perfect sense that a frightened America would elect Republican Richard Nixon to the presidency that November.

It was really only a matter of time before gays got angry enough to start fighting back. Beginning in March of 1969, the New York Police Department stepped up its periodic raids on gay bars; the June 28 raid on the Stonewall Inn was simply business as usual. After three nights of unrest women and men began to organize, and weeks later the formation of the Gay Liberation Front was announced. The group was a direct, and important, result of the Stonewall riots.

But Stonewall was not the end of this national narrative, just a small moment in time. Two months after the birth of the Gay Liberation Front, Students for a Democratic Society staged its largest national demonstrations. National protests against the war in Vietnam increased, and in November an unprecedented quarter-million people marched on the Pentagon. Although inconceivable a decade earlier, American society was in full-throttle revolt against racism, oppression of women, sexual repression and the deadly foreign policies that were destroying lives in the US and abroad. Is it any surprise that by the middle of 1970 there were already more than 300 independent chapters of the Gay Liberation Front across the country? It wasn’t just that gay liberation was an idea whose time was ripe, but rather that in this context of multiple fights for massive social change, it was an idea that was inevitable.

What was incredible about the Gay Liberation Front, and what is so sorely missing from our gay rights movements now, is that it saw itself as a multi-issue radical movement.

It was as concerned with ending wars abroad, fighting racism, and securing reproductive freedom for women as it was with fighting homophobia. Members of the Gay Liberation Front also understood that they needed, pragmatically and philosophically, to work in coalition with other movements.

For me, as a young queer who had already been working with Students for a Democratic Society and had been involved in civil rights and women’s rights issues, gay liberation was a revelation that brought together all my political and emotional concerns.

The vision of the Gay Liberation Front linked freedom for gays to the freedom of all other oppressed groups. It is a vision that neither the homophile groups that preceded it nor the gay rights groups that followed understood or embraced. It is a lesson the gay rights movement just might be learning now.

The importance of Stonewall resides not in a sentimental vision of it as a sort of community coming-out story but in its unique place in the panoply of movements, events, riots, demonstrations, political actions, social revolts, bad behaviours and bursts of anger that defined the second half of the 1960s. By all means, let’s celebrate the 40th anniversary of Stonewall this month, but let’s also remember that it is not just about gay equality; it is about the broadest vision of social change and social justice the US has experienced in our lifetimes.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra