Little Sister’s Book & Art Emporium was the first place I went to in Vancouver to buy books after I came out in 2003. I was a 24-year-old femme just barely out of the closet, searching for stories to help me understand myself, my desires and the communities I hungered to be part of.

Before coming out, I haunted the stacks of my university library, where a small collection of books about queer lives—only some of which had been written by actual queer people—were housed on tall, beige, metal shelves in a dimly lit corner. Walking into Little Sister’s was like crossing the threshold into a world where the vibrancy of queer self-expression was in view everywhere.

I had never been to a queer bookstore before. If my university library’s collection of queer books was a morsel, Little Sister’s was a feast. The store had warm brown wooden shelves filled with row after row of books on every subject I could imagine, from self-help books to biographies to sex how-to guides, and many I hadn’t even thought of, like queer horror anthologies, lesbian mystery novels and gay science fiction.

Little Sister’s didn’t just sell books. They sold a colourful mix of T-shirts, hats, greeting cards, dildos, jock straps, safer-sex supplies and enough rainbow-themed accessories to outfit a whole Pride parade. I bought a tiny rainbow enamel pin shaped like a high heel—my way of flagging femme.

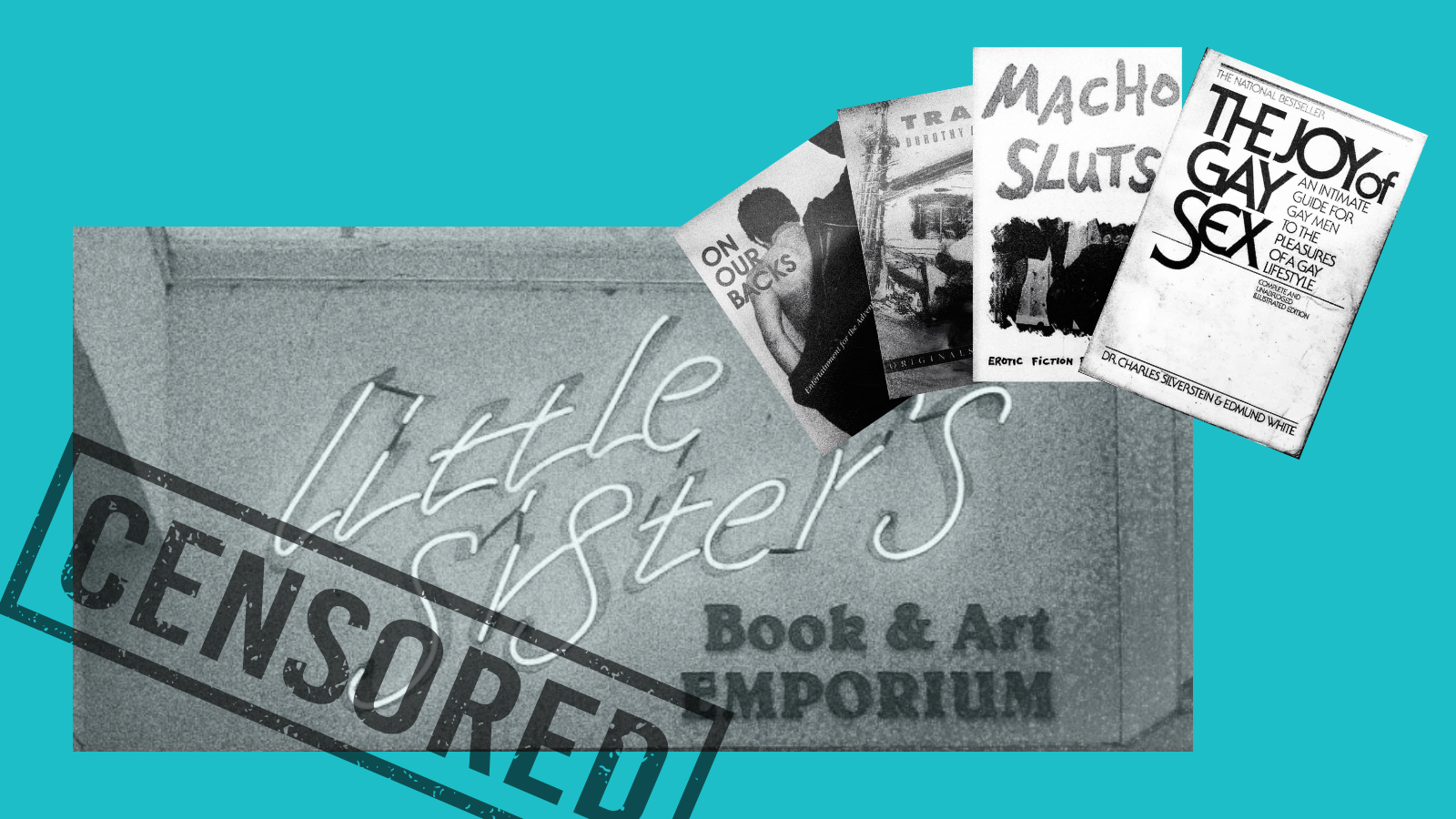

Little Sister’s also sold magazines. Some, like Curve or The Advocate, covered queer lives, culture and politics. Others, like On Our Backs and Drummer, featured explicit depictions of queer sex and BDSM. I was too shy to flip through them in the store but my eyes were drawn like magnets to their covers. It would be a few years before I felt daring enough to look at them, and longer still before I was proudly reading my copy of Patrick Califia’s Macho Sluts on the bus.

As a newcomer to Vancouver’s queer community in the early aughts, I had the vague idea that Little Sister’s had played a pivotal role in fighting for my right to read queer books. But I knew next to nothing about their lengthy battle over censorship with Canada Customs (renamed Canada Border Services Agency in 2003)—a battle the bookstore took all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada and won in 2000. This December marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of their victory. Defending queer books against censorship is as important today as it was twenty-five years ago, as the battle is far from over, even if some of the battlegrounds have changed.

I came to Little Sister’s as many people did, drawn to the Davie Street store by its welcoming atmosphere and reputation as a beloved community institution. I took for granted the presence of all those queer books on the shelves, not realizing how tenaciously the store’s co-founders, Jim Deva and Bruce Smyth, and Janine Fuller, who managed Little Sister’s from 1990 to 2015, had fought to keep them there, or what they had weathered in the process.

Their journey to the Supreme Court took 15 years, cost hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees and made targets of the store and its staff. Little Sister’s was bombed in 1987, 1988 and again in 1992. Fuller told of receiving hate mail and death threats in Little Sister’s vs. Big Brother, filmmaker Aerlyn Weissman’s 2002 documentary about the Supreme Court case.

Little Sister’s had its first clash with Customs in 1985 over a seizure of lesbian magazines, just two years after opening in its original location, a second-storey walk-up on Vancouver’s Thurlow Street. There, Smyth and Deva slept in a tiny back room behind the bookstore, where customers could browse books, drink coffee, play pinball and buy cigarettes, poppers and lube.

Customs raised the stakes in December 1986 by seizing a shipment of more than 600 books and magazines destined for Little Sister’s, claiming they violated Canada’s obscenity laws. The loss of so much stock put the cash-strapped store’s finances on the line. “That’s when we figured out they had the power to put us out of business,” Deva told Xtra in 2008.

Determined to fight back, Little Sister’s launched their first legal challenge against Canada Customs in May 1987, in partnership with the BC Civil Liberties Association. Three years later, in 1990, they launched a constitutional challenge, arguing that Customs discriminated against queer people by violating the freedom of expression guaranteed under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. At the heart of their case was the argument that queer sexual expression and imagery had real importance and value, entitling it to the highest protection in law.

Little Sister’s sought to hold Customs accountable for targeting queer bookstores and queer books. Customs had a pattern of systematically detaining shipments destined for queer bookstores while other bookstores in Canada were able to order the same titles without interference. Meanwhile, Little Sister’s and Toronto’s Glad Day Bookshop, Canada’s first queer bookstore, founded in 1970, were “subjected to delays and detentions every month, often weekly, for years,” wrote Janine Fuller and co-author Stuart Blackley in their 1995 book Restricted Entry: Censorship on Trial.

Customs/Border Services Agency has had the power to stop printed materials from entering Canada on the grounds of immorality or indecency since before Confederation, power that was enshrined into law in 1867 at the first session of the Canadian Parliament. By the early 1980s, Customs was using this power to systematically target queer bookstores and queer books.

They weaponized the label of obscenity against materials destined for queer bookstores. One of my favourite short-story collections, Dorothy Allison’s Trash, inspired by her experiences as a working-class Southern queer femme survivor, was once detained because Customs mistook it for another previously banned book of the same name. Rather than double-check for errors, they simply didn’t allow it into Canada.

Many books and magazines were seized, and in some cases their entry into Canada was prohibited for their depictions of anal sex, prompting Glad Day Bookshop to sue Customs in 1986 over its seizure of The Joy of Gay Sex, a book that had been widely available in Canada since it was first published in 1977. In his decision, an Ontario District Court judge wrote, “To write about homosexual practices without dealing with anal intercourse would be equivalent to writing a history of music and omitting Mozart.” Glad Day won their case against Customs, but that didn’t stop the agency from continuing to target queer bookstores.

The suppression of gay periodicals destined for bookstores like Little Sister’s was particularly cruel during the AIDS crisis, when these titles were a reliable source of guidance on safer-sex practices and emerging community knowledge about the virus. In Little Sister’s vs. Big Brother, Smyth recounted phoning a gay bookstore in the U.S. to have a staff member read him an article called “10 Safe Ways to Have Sex” after a 1985 issue of the gay porn magazine Blueboy was barred from entry into Canada.

“As a younger queer person coming of age soon after Little Sister’s won its Supreme Court victory against Canada Customs, effectively stemming the tide of book seizures, I took for granted my freedom to read queer books—including the BDSM erotica that still holds pride of place on my bookshelves today”

“Nothing seemed to bother Customs as much as gay and lesbian S/M,” wrote Fuller and Blackley in Restricted Entry. My beloved Macho Sluts, Patrick Califia’s 1988 collection of queer BDSM stories, was particularly controversial. Little Sister’s former buyer Mark Macdonald wrote in his preface to the 2009 reissue of the book that an entire shipment would be detained if Macho Sluts was included in an order from Little Sister’s U.S. distributor. The title was detained, prohibited, reviewed and released by Customs on multiple occasions, yet the bookstore kept ordering it, prompting author Califia to speak in Little Sister’s defence during the trial.

“Censorship is never about whether anyone should be able to read or see something. It’s about who can read or see it,” wrote author and lawyer Marcus McCann in a 2019 essay on defending queer expression. As a younger queer person coming of age soon after Little Sister’s won its Supreme Court victory against Canada Customs, effectively stemming the tide of book seizures, I took for granted my freedom to read queer books—including the BDSM erotica that still holds pride of place on my bookshelves today, as well as the dozens of other queer books lining my shelves.

In 2025, we are again facing a wave of censorship of queer books in which labels like “obscene,” “inappropriate” and “pornographic” are being weaponized against us. While Little Sister’s battleground was the border, today’s would-be censors have their sights on schools and public libraries. I’m reminded of something filmmaker Aerlyn Weissman, who is quoted in Restricted Entry, said at a 1994 fundraiser for Little Sister’s: “We are all talking about ‘when this trial is over,’ but this struggle will never be over.” Weissman’s words seem especially prescient today.

Librarian Michael Nyby has documented the persistent targeting of books with LGBTQ2S+ themes in challenges in Canadian libraries, with the Alberta government borrowing tactics directly from the far-right playbook. In the U.S., “persistent attacks conflate LGBTQ+ identities as ‘sexually explicit’ and erase LGBTQ+ representation from schools,” wrote PEN America in its October 2025 report, The Normalization of Book Banning. Incarcerated people also face censorship, with bans on “homosexual literature” in states including Louisiana, Mississippi and South Carolina preventing them from accessing queer books through prison libraries.

A book can be a mirror, reflecting back to us who we are, or a window that opens us to whole new vistas of possibility. The first time I walked into Little Sister’s, I was a young woman searching for community and learning to imagine a queer future for myself. The people I met behind the counter there had fought fiercely to defend my right to read the books that helped me understand myself as a queer femme—the histories I needed to feel part of a lineage, the stories I needed to know I wasn’t alone and the sex writing that unleashed my desires.

Today, I’m a middle-aged queer femme writer about to publish my most personal and erotic book —a collection of essays I’ve dubbed my horny grief memoir. I like to think it’s the kind of work that might have been seized by Customs had it been imported into Canada in the 1980s and 1990s.

My memoir is indebted to the queer radical and sexual outlaw lineages that make it possible for me to live, and write, more freely. I sought to honour their courage and daring by telling my story as honestly as I could, in the hope that my writing might be a mirror, or a window, for someone else. May we all keep up the fight to ensure that everyone has the right to read books that have the power to show them who they are.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra