When we first meet Adrian, one of two protagonists in New York writer Davey Davis’s third novel, Casanova 20: Or, Hot World, he is a young boy growing up in northern California, whose undeniable beauty arouses obsession in strangers, and fear and resentment in his family members. His parents, aunt and grandmother treat him as if it’s his fault that strangers follow and grab at him in public. They do not attempt to talk to him about these disquieting encounters, and though they seek to protect him, they do so ultimately only to protect the family from unwanted attention: “Like death, his beauty was dreadful, inevitable, and never to be spoken of in front of the boy unless it couldn’t be avoided.”

Adrian grows up to be beautiful, constantly sought after and provided for, and happily promiscuous (he favours women but has an inclusive appetite), but also passive and carrying a strange emptiness inside of him. His close friendship with Mark, an older, famous gay painter, who is contending with his own mortality, is the central relationship of this dreamlike book, and just as elusive. Davis traces the two men’s stories, which intertwine closely even as they avoid telling each other their deepest fears, against the backdrop of 2021 New York, during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Through Mark and Adrian, Casanova 20 evokes the overwhelming feelings of loss and alienation that have accompanied the pandemic, and connects the pandemic’s deaths and disappearances to those of the AIDS epidemic, as well as the toll of other autoimmune diseases, while asking big questions about beauty and ugliness, desire and intimacy. At the start of the novel, Mark has just buried his mother and sister, who have both died from an unknown autoimmune disease. The necessary isolation of the pandemic renders these losses even more lonely than they would otherwise have been. He has recently discovered that he is dying from the same disease, but he can’t bring himself to talk to anyone about it. Having already lost his romantic partner, Arturo, to AIDS years ago, he avoids telling Adrian, his closest living companion—other than his cat George—about his own imminent death. Meanwhile, Adrian, accustomed to gliding by on his youth and beauty, is suddenly contending with the loss of his powers. It’s summer 2021, and as vaccines become available and people start unmasking in public, Adrian discovers that his beauty and the intuition with which he wields it, which he refers to as it, has faded, leaving him unmoored. He is a Dorian Gray-like figure, although instead of a secret ugly painting, he hides an inner emptiness, a passivity and lack of agency that threaten to overtake him once it begins to desert him. Twink death, but for a mostly straight man.

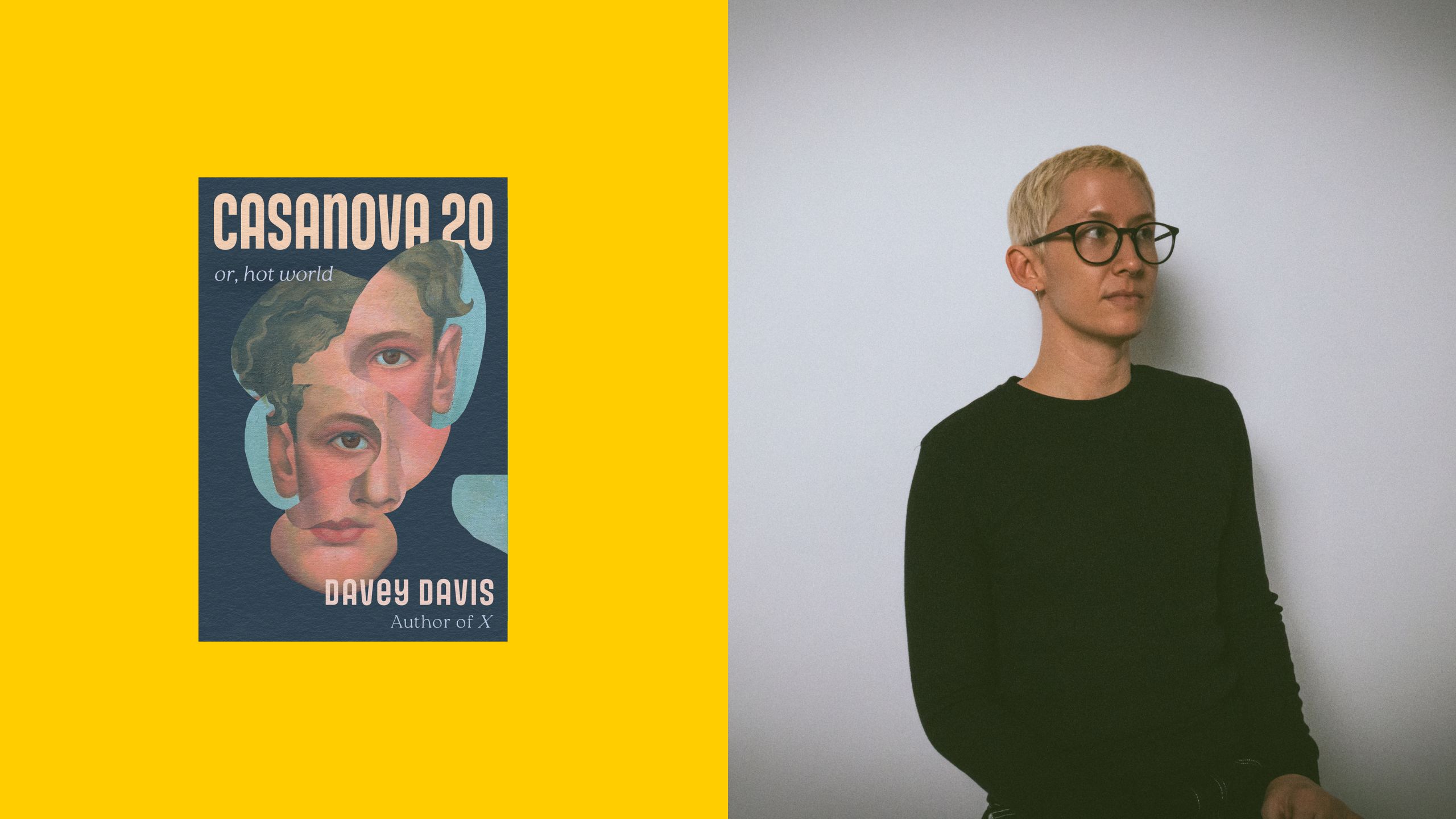

Davis is the author of two previous novels, the earthquake room, and X. The latter of these is a queer noir set in a near-future authoritarian New York, taut and urgent, driven by its protagonist’s search for X, a mysterious top, amidst the city’s queer clubs and play parties, which are slowly emptying out due to mass deportations. Davis is also the author of DAVID, their incisive and wide-ranging newsletter, which focuses on the politics of illness, trans bodies, pain and pleasure, as well as queer and trans history and cultural artifacts. Casanova 20 features many of these preoccupations—the strange particularities of intimacy, the violence of desire, how illness reshapes bodies and communities, how governments are driven to abandon or kill marginalized people; however, this novel is much more stripped down than X, with a more subtle narrative drive.

Casanova 20 is the first novel I’ve read that really contends with both the material concerns and the emotional effects of the pandemic. Davis describes the practice of masking, including the social aspects of it—how wearing a mask can be inhibiting, but also socially protective. Adrian, accustomed to being a public spectacle wherever he goes, experiences the delight of being unseen: “Was this what normal people felt like? Masked, he can watch without being watched back, and he has been pleased to discover how much he enjoys it.” At the same time, once people are able to take their masks off in public, thanks to vaccines, he notices that something about New Yorkers has changed since the pandemic began. Their brusqueness, their “terribly alert unselfconsciousness,” which he had liked, has been replaced with a new expression: “The people around him have removed their masks after a long, brutal year to find that something is missing.” The question of what exactly is missing permeates Casanova 20; there is no answer, or there are countless answers. Its characters are both panicked and aimless, bemused by the changed world, and their new powerlessness within it.

Adrian and Mark’s friendship ties the novel’s parts together, and yet it is a somewhat inscrutable relationship, in ways that both serve and hamper the text. Theirs is neither a gay partnership, nor an easily defined friendship based on common interests; they are extremely comfortable in each other’s company, though they talk very little; they often share a bed, yet never have sex. Mark is one of the few people who is, for whatever reason, immune to it, which is perhaps what draws Adrian to him. Mark takes care of Adrian financially, and Adrian, now that Mark is ill, takes care of Mark physically: cooking and cleaning for him, wiping his face after he vomits in the bathroom, again and again. There is tenderness here, but it is almost entirely unspoken, transmitted to the reader only in brief scenes of wordless cohabitation.

Their relationship recalls that of celebrated filmmaker Derek Jarman and his long-term, non-sexual partnership with Keith Collins, or Hinney Beast, as Jarman affectionately called the younger man. Collins, who had a boyfriend of his own, was Jarman’s frequent companion during the artist’s later years, as he became sick from AIDS-related illnesses. Twenty-four years Jarman’s junior, Collins was young and beautiful, like Adrian. Collins was not often recognized as an artist in his own right, even though he acted in Jarman’s films and collaborated with him on various other creative projects—he was Jarman’s closest relationship, his caregiver, his friend, his muse and his great love, despite this love not being typically romantic/sexual. Adrian, for his part, is not interested in art, not even Mark’s art—he’s supportive but not appreciative. Mark pretends to be miffed by this, but in fact, “Adrian’s distaste made him feel cool. Like he was so secure that he could keep someone around who was real with him.” Mark’s art-world fame means nothing to him once he becomes ill; Adrian is the one who remains by his side, who doesn’t ask anything of him, once he can no longer safely leave his apartment.

Though we can glean some understanding of their relationship from the text, the fact that Mark and Adrian spend little time together in the novel leaves a lot of blanks to fill in. We are told that they are very close, but the intimacies of the friendship are rarely present in the text. Their conversations are often stunted: “Do you want me to move this?” “No. It’s fine there.” “Okay.” Granted, Davis’s decision to write these mundane exchanges between them serves to highlight everything that is going unsaid; however, sometimes it feels as though Davis pulls back too much, avoiding the risks of over-sentimentalizing the relationship, but also leaving a frustrating vacancy at its centre. A line in the text provides some explanation for this sense of hollowness: “Losing Arturo was an inversion of Mark’s natural life. Now everything is outside, and nothing within.”

Mark spends increasing amounts of time in his bathroom, hunched over the toilet in pain, sweating and expelling, amidst photos of his old life, pictures of his younger self hanging out with famous friends, like Scott Walker and Jimmy Somerville and John Lurie. Pain moves through his body, slow and thick, as if he were “one of those plastic bears that are pumped with honey.” Meanwhile, Adrian is lost without it, purposeless and unaccustomed to being unseen or ignored in public, once the novelty of this has worn off. In between bouts of time spent at Mark’s apartment, he cruises in Prospect Park, desperate to regain his power. It is still there but only sometimes. He finds himself trying to stack encounters, which he rarely does—he’s never normally insatiable, because he used to know that there was always more. Now, he wants more, and is alarmed and deflated each time he expects a stranger’s desire and doesn’t receive it. His friend Cora notices that something about him has changed—“He looks like a garden statue in the winter: there’s no one to observe him.”

Perhaps it’s helpful to read Casanova 20 as Davis’s contribution to something I want to call a queer literature of aftermath, alongside Gary Indiana’s Do Everything in the Dark, a grimly funny novel about middle-aged queer artists in the early 2000s, whose lives have caught up with them in various disastrous ways; or Nate Lippens’s recent Ripchord, which covers similar ground; or Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s So Many Ways to Sleep Badly, which documents its protagonist’s chronic pain and anxiety in the ruins of San Francisco circa 2008. Davis’s book is lacking some of the crackling humour of these other entries, but fits comfortably among them.

Toward the end of the book, Mark battles insomnia as his illness worsens. For entertainment or at least for company, he has a stack of mysterious VHS tapes left behind by his sister, who was archiving them for another artist. Each tape contains a film—anything from a romance, to a Western, to a slapstick comedy, to a Quixotic adventure story, but though they bear the features of real movies, there are no recognizable actors in any of them, and never any ending credits.

The films seem to encompass every kind of narrative or desire that might exist—playing on as Mark drifts in and out of fitful sleep, like fragments of dreams. His own desires have left him—he can’t even go on the “world’s biggest, most beautiful bender,” something he’d imagined doing if he ever got so sick that he had to stop painting. Instead, he wakes up every morning, anticipating that old compulsion, but it never comes. Desire has left him, just as Adrian finds himself unable to ignite it in others the way he used to.

The videotapes are like surreal remnants of the world that used to be—before the pandemic, before the deaths of lovers and family members, before the loss of desire. “I just need you here sometimes,” Mark says to Adrian, in a rare show of need and emotion, as Adrian is flitting in and out of the apartment, trying to regain his own sense of control. And so, Adrian stays with him, a simple gesture and yet perhaps the most important mode of love that they share. “It’s not what I expected,” Mark’s sister had said to him, when she was dying. The world as it is now isn’t what any of us expected, Davis reminds us: the implications of each new disaster are hard to absorb, our inner and outer worlds may seem impossible to reconcile, the things that are disappearing become difficult to name, and yet many of us remain, sitting side by side with our friends in the ongoing aftermath of loss.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra