“Any honest description of survival isn’t inspirational, it’s frightening,” writes Nate Lippens in Ripcord, his second novel. This line, spoken by the book’s unnamed narrator, refers to the character’s taste in poetry, to his distaste for pieces of writing that are supposedly universal. The narrator prefers poetry that others claim is not poetry, narratives that are the opposite of uplifting. A more optimistic friend takes him to see a “strenuously life-affirming movie” and he is quick to pick it apart afterward, gesturing at its emptiness. Ripcord is a novel that lovers of the life-affirming narrative or the tidy trauma plot might shy away from; it is often frightening in its directness, its refusal to lean into empty optimism, its insistence on keeping death in view. It is also, for these same reasons, a galvanizing read that records a fragmented intention to continue existing, at least for now, despite the many reasons not to.

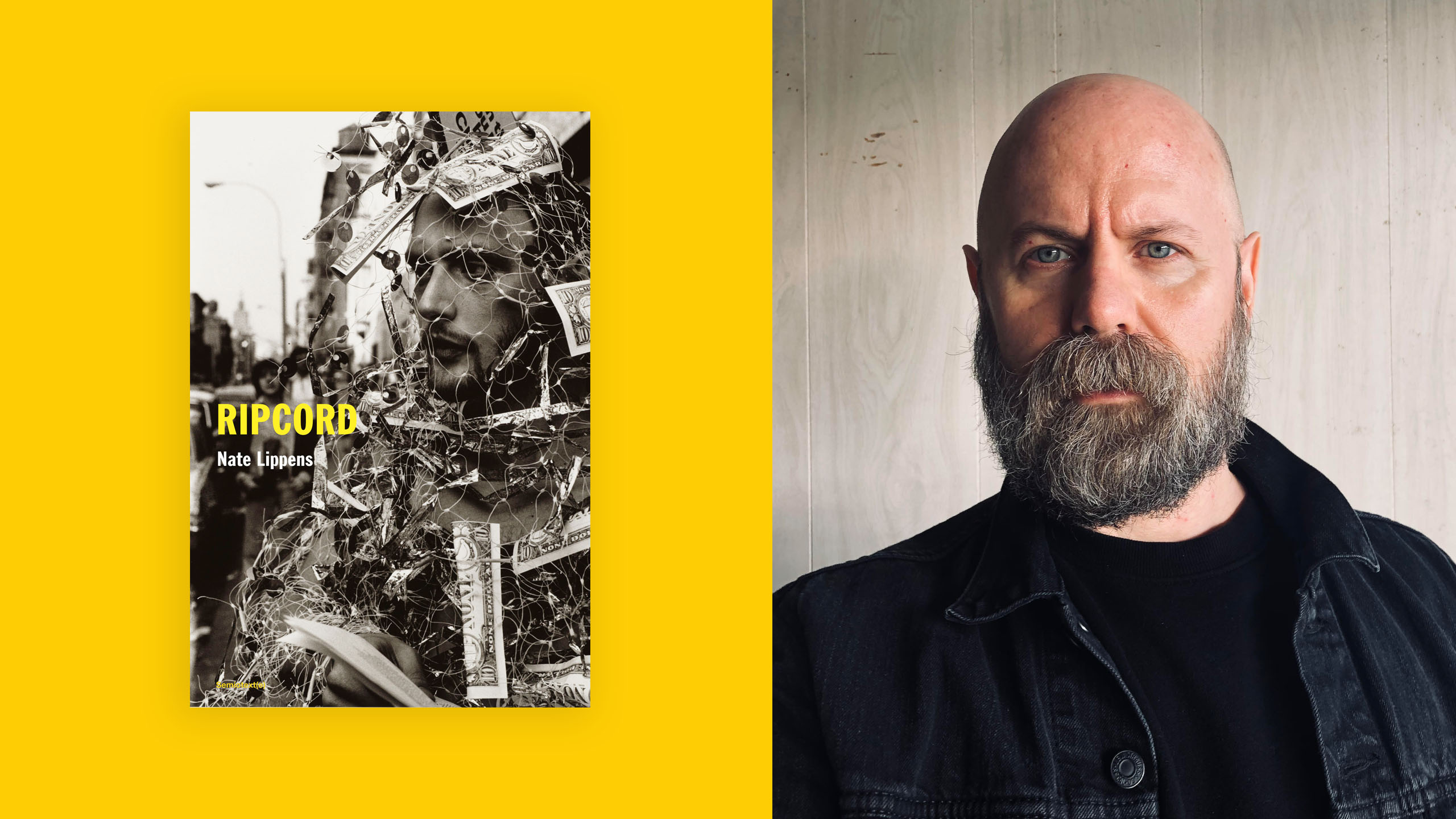

Lippens’s debut was My Dead Book, published in 2021 and a finalist for the Republic of Consciousness Prize. My Dead Book’s narrator, haunted by insomnia and the past, flips through memories of dozens of friends who aren’t around anymore, and reflects on his own history as a teenage runaway. Ripcord’s narrator returns to this ruminative space. He’s a middle-aged white working-class gay man living in Milwaukee, working bar shifts and catering gigs, engaging in a sort-of affair with a younger married man and living somewhere between the past and the present. Often stuck in bed or on his couch with the “black dog” of depression, other times navigating the icy streets of his city, he tallies the many losses of his life, with a growing sense that love, at least romantically, may be over for him.

Lippens joins the ranks of working-class queer writers like Eileen Myles, Michelle Tea, Brontez Purnell, the late Dorothy Allison and others who write class intentionally into their work—the blunt details of day-to-day living on low wages and bad jobs, the indignities of capitalist demands, the rejection of upward-mobility fantasies, the aversion to easy outs or comforting pronouncements—and the biting humour of all of this too. Ripcord is a novel about middle age that does not fit the typical arc of “mid-life crisis makes protagonist reconsider their life”—because, as the narrator points out, those stories assume a certain level of financial stability and a certain type of normative life up until the point of crisis. What about middle-aged queer people who have never had “normal” life trajectories, who have no established place of comfort from which to fall apart? Lippens is specifically interested in the lives of working-class queer artists who “want love and freedom” like everyone else but have been thwarted over and over by capitalism and heteronormative structures. “I am an institutionally illegitimate person and I conduct myself accordingly,” the narrator says. A friend’s preteen child asks him why he isn’t married, and he replies that this simply wasn’t an option when he was younger. Now that it is, he doesn’t consider it. Part of being a working-class gay man who came up in the 1990s was rejecting victimization by raucously embracing everything that was said to be wrong and disgusting about him. As he puts it, “Some people get the glory. Some people get the glory hole.” His friend Charlie, an aging queer punk, writer, collagist and collector of printed matter which he refers to as “My Heap,” agrees: “Why not age disgracefully?”

Charlie’s heap of printed materials and his penchant for collage provide a structural guideline for novel itself: it’s composed in fragments, which at a glance might seem to be arranged at random, moving between distant past, recent past and present; between various lovers and exes and friends and jobs and ruptures and cities. A recent ex of the narrator complains that collage is a tired art form, calling it “cobbled together garbage.” “Yet here I am,” says the narrator, “pretending to be a whole person.” Who isn’t?

In fact, this fragmentary approach mimics the eddies of living more accurately than a linear narrative does, or at least it mimics the way an agitated mind attempts to make a story out of all of the life that has come before this moment. Lippens’s prose has a startling, immediate quality to it, so that past recollections and regrets share a plane with the narrator’s current state, whether that’s listening to regulars’ complaints at his bar shifts, or considering a graffiti invective to “Kill the rich (no exceptions—sorry),” or lying in bed for days, letting time run together.

“This question of what makes a whole person or a life worth consideration permeates Ripcord.”

In an interview with Lippens about My Dead Book, Lindsay Lerman calls that novel “a living book (a living dead book),” which applies to Ripcord as well. Living, in that it does not feel like a fixed object that has been edited into a finished statement, but rather like an ongoing conversation between the narrator and his memories, as well as with his friends, who appear frequently in the text, both alive and dead. A life cobbled together is a life, even if it’s less marketable than a life that attains expected goalposts, or that vaunts its own legitimacy via the accrual of possessions and pithy nuggets of wisdom.

This question of what makes a whole person or a life worth consideration permeates Ripcord. Lippens’s narrator is a curmudgeon, a self-avowed pessimist, which he is quick to differentiate from the cynic: “If I were cynical, I’d be making money. Cynics get rich. Pessimists stay poor.” Lippens’s pessimistic narrator isn’t screwing anyone else over; snapshots of lost friendships and relationships punctuate Ripcord, but we get the sense that these breakages are the result of old wounds and harsh material circumstances, rather than of denying the worth of other people. A memory of the narrator’s first devastating rejection resurfaces several times throughout the novel: at 15, his mother kicked him out of the house—her home, never his home, as the text is careful to specify. Devastatingly, she uses the language of breakup with him—her son, a teenager: “This isn’t working,” she tells him, during a tense car ride, as if she’s a lover working up to dumping him. Later on, she lies and tells everyone he ran away, and he doesn’t dispute this, instead adopting her version of events as a method of self-protection: in this revised history, he can take on the role of the rejector.

Of course, the wound remains. In his adult life, he is deeply suspicious of lovers’ promises. Their optimistic proclamations alienate him. He remembers his recent ex telling him he’ll “give [him] a beautiful life,” how though he wanted to believe this, he was also immediately dismissive of this language, the arrogance he read into it. How can anyone presume to make such a promise? he wonders. He can’t believe in the comfort of romantic love. Even the relief of drugs is in the rear-view mirror—he’s a recovering heroin addict, and speaks of those past highs like long-departed exes. “A horrible thought: Nothing will ever hold me as well as heroin did … for a brief time the high was the best sensation I had ever had. And I can never have it again.”

When another breakup occurs in the narrator’s life, he struggles more and more to get out of bed, to go to his work shifts. The accumulation of lost friends, lovers and relationships is overwhelming, and he is frequently assailed by the terrible fear that every decision he makes is the wrong one—or, as he puts it, “every choice an invitation to regret.” He imagines doing what he used to do frequently when he was younger: cut his losses and leave town, get out and go somewhere else, try to forget the painful breakages, start again. But he’s not so young now. Death winks from the sidelines, in the form of Sam, a dear friend who died from AIDS complications years ago, and in the form of high bridges to jump from. Lippens does not grant the reader the feeling of safety that comes from books that make wise pronouncements about the past, as if the past is now over—we are not offered the false comfort of the author having come to a helpful conclusion, or at least one that distances us from the painful events of life. Instead, painful things continue to happen. Ripcord knows this; as a living novel, it is a record of keeping on.

Losses accumulate, and yet, sometimes lost things are retrieved. Some time ago, when the narrator started working a catering gig, he made enough money to buy back the Nan Goldin monographs he’d sold off during his heroin addiction. Goldin is herself an artist who is concerned with making it possible for people to keep on living, under the weight of capitalism, unsupported addiction and the tyranny of the pharmaceutical industry. The narrator’s artist friend, Greer, who in middle age has not achieved professional recognition or financial security, nonetheless continues to make art, to be enlivened by new ideas. The narrator and his friends look to other artists for examples of ways to live, or at least to keep making art. Greer recalls a story about the painter Agnes Martin, who was hosting a young painter at her home in New Mexico, and gave the following advice: “Never have kids, never live a middle-class life, and never let anybody in your studio.” As she said this, she opened the door to her studio. Maybe the contradiction is the key to this question of how to live as an aging queer artist. Never let anybody in, but open the door anyway.

Ripcord, a novel narrated by a speaker who often rejects the company of others and doesn’t like to reveal the weight of his sadness even to his close friends, nonetheless opens his studio door by recording his fragmented reflections and memories, which are deeply emotional, even as they explain why he can’t let himself be so. Ever allergic to words like “affirmation” or “perseverance,” Lippens’s narrator commits, ultimately, to keep on going—for now. “Isn’t it enough to still be alive and more or less intact?” he asks. “I consider that astonishing.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra