“The personal is political” was a rallying call of second-wave feminism. It highlighted the crucial ways in which everyday women’s concerns—like childcare, the “second shift” and reproductive rights—reflected larger structural inequalities caused by the patriarchy. Engaging on those personal grounds was transformative work.

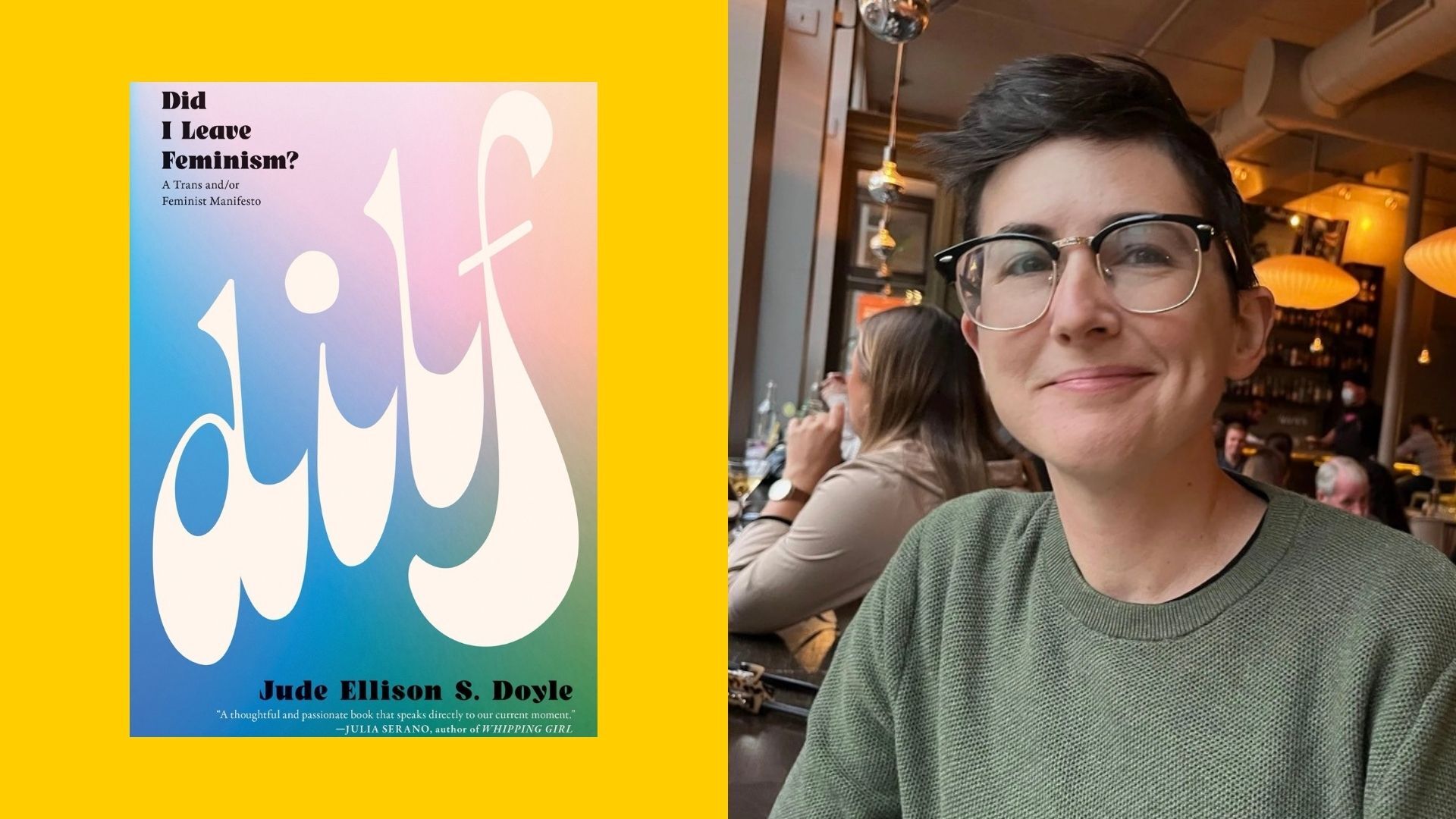

But what happens when a feminist’s own life and identity changes so radically that those everyday concerns become unintelligible? Can you still even be a feminist once those personal issues cease to pertain to your own life? Or worse, when you begin to be seen as participating in the oppression itself? This was the existential question faced by feminist writer Jude Ellison S. Doyle when he undertook his medical transition in the 2020s, leaving behind his life as a woman to join the ranks of men in our society.

These are complicated questions. As Doyle (who is a regular contributor to Xtra) makes clear in his new book Did I Leave Feminism? (DILF): A Trans and/or Feminist Manifesto, he may have experienced a new kind of gender socialization once the world began seeing him as a dude, yet he still had his life experience from the years when it thought he was a woman—which included borderline sexual assault and extreme misogynistic abuse as a phone sex operator. He still also has the vulnerability that comes with the social position of a trans man—even if he’s not always read as such. As he puts it in DILF, “How can someone be a man while also experiencing a form of oppression we almost always classify as a ‘woman’s issue?’”

In DILF, Doyle explores the complexities of what his life and transition mean for his feminist advocacy, while also waging an impassioned re-evaluation of the second wave, often fighting to bring a kind of restorative justice to the concepts and individuals who have been deemed too regressive and too transphobic to be of any value to feminism today.

Across the sweep of the book, Doyle tries to figure his way out of the condescending boxes that feminism has enjoyed putting trans men into (when it even thinks of them at all): either they are apostates to the female gender who must be forced back into the fold at all costs, or they are fraudsters who have found the cheat code to escape gendered oppression altogether. On the latter point, Doyle passionately argues that trans men’s history experiencing oppression as presumed women doesn’t somehow render them invulnerable to the toxic parts of masculinity (as a woman who has known a diversity of trans men, I would agree). Yet Doyle also refuses to give in to facile man-hating, instead making an honest effort to empathize with the violence that patriarchy does to both women and men (while also, it must be said, granting women our legitimate anger).

Doyle recruits some interesting allies in this effort, including the late Andrea Dworkin and her partner John Stoltenberg. In his interview with the latter, he reveals Stoltenberg to be a big advocate of non-binary identities, while also lauding him for being willing to “stand up, burn bridges, make a ruckus about trans people’s rightful place in feminism.”

Dworkin has become a sort of cause célèbre lately among TERFs, particularly since Stoltenberg penned an infamous 2014 essay in which he argued that she wasn’t a transphobe. This has caused trans-haters no shortage of ire—including one who blames the “transing” of Dworkin on a nefarious plot hatched by Stoltenberg himself.

Doyle largely eschews these debates (although he does address Dworkin’s rave on the cover of Janice Raymond’s The Transsexual Empire—the urtext of TERFism), and he does admit that a lot of Dworkin’s feminism just doesn’t read very well any more. But, arguing that he reads feminism like a cook reads cookbooks, he pulls out one Dworkin “recipe” that he has a fondness for.

The recipe in question turns out to be Dworkin’s infamous dictum that “intercourse is the pure, sterile, formal expression of men’s contempt for women,” or, as Doyle glosses it, intercourse is “about the ritualized affirmation of men’s social and physical dominance over women.” For the record, Doyle states that you can have penetrative sex and still be a good feminist (glad to have that clear!), and instead reads Dworkin as essentially saying that “heterosexuality, the institution, is structurally violent—set up to produce violence, not a rare tragedy, but as a regular and expected outcome.”

The inherent violence of patriarchy is a lynchpin of the feminist arguments that Doyle makes in DILF, and it’s also at the root of his own angst over where feminism leaves trans men. He inventively finds an escape route that is pretty compelling.

Tweaking Dworkin (or, one might say, queering her), Doyle makes a rhetorical move that is central to his premise: he argues that if you take patriarchy’s violence as a given, then you put sexual and gender marginalized groups on the same side. That is, cis women and trans women are both losing under patriarchy. So are gay men, and Black women, and non-binary folks and, yes, even trans men.

Aligning the interests of all sexual and gender marginalized groups under patriarchy is DILF’s big insight, letting Doyle both redeem so much of the second wave and bring trans men like himself back into feminism. If you simply note that trans people and cis women are both engaged against the right wing in a desperate struggle for bodily autonomy (one over gender-affirming care, the other over abortion), or if you simply note that trans women are actually much more likely to experience sexual violence than cis women, then suddenly the second wave’s big lie of the “biological male” aggressor coming in and stealing what rightfully belongs to the “real women” disappears.

It’s a great argument, though one thing Doyle doesn’t contend with in DILF is that a lot of women today are actually very happy to let go of their bodily autonomy and to be the dominated gender in the patriarchy. A good 45 percent of U.S. women voted for Donald Trump in 2024, and there is of course the tradwife phenomenon and even hard right trans women like Blaire White and Caitlyn Jenner. It is well known that the anti-trans playbook was widely cribbed from the anti-abortion one, and Doyle himself notes in a Medium essay that prominent TERFs actually advocate against a woman’s right to choose. One wonders what Doyle would have to say about what feminism can offer to such women, particularly given that at least some of them adopt the “feminist” label for themselves.

Doyle also argues for feminism embracing new ways of holding traditional concepts like gender and the family. He fondly quotes second wave firebrand Shulamith Firestone, who argued that since humanity has long since used technologies like vaccines and toilets to escape the confines of our biology, we should also do that when it comes to gender. And he makes the argument that when it comes to queer—and especially trans—children, it really does take a village, as oftentimes the cishet parents of such offspring will be at a loss in a way that tends not to happen with more biologically or culturally inheritable forms of marginalization. Drawing on the case of Nex Benedict, a trans teen who died by suicide after being bullied for years, with the tacit endorsement of their school, Doyle makes the case that having a loving parent isn’t enough, since the world is so dangerous to trans kids:

Whether or not we are parents, whether or not we have trans children at home, we have a responsibility to make the world safer for trans kids … Care for those children can be our most fundamental form of resistance; there can be trans people who have never hated themselves, never doubted themselves, never been alone or lonely, so long as we are there for them from the moment they show up.

To that point, it would have been interesting to see what Doyle would have done by adding a disability lens to his argument—for instance, parents of deaf children have long had to wrestle with the ways in which they are challenged to best care for their little ones, with their ability to engage a Deaf culture that they feel outsiders to, and with a world that is often unsafe for and unempathetic to their kids. In both cases, the burden often falls onto professionals—be they teachers, administrators, counsellors or medical providers—to take up much of the slack and to educate parents on how best to support their children.

Deep in the trenches of his own medical transition and feeling the sheer duration of that process, Doyle concludes DILF with a passionate argument that “our genders are not stable or fixed states of being” and thus “no one ever becomes a man or woman, because we are always in the process of becoming.” Citing Thich Nhat Hanh, the famed Buddhist monk who has prolifically written on the benefits of mindfulness, he sees this instability and uncertainty as sources of great virtue.

As someone who has changed my sex, I understand where he’s coming from. I do vividly recall my own transition days, when it seemed like everything in my life was in flux and that my gender would endlessly be a point of contention for the rest of my life. Now, having become a fairly normal woman (albeit one with a penchant for adrenaline and tattoos), that all feels quite distant from me, the day-to-day of my gender gladly mundane and predictable. Yes, I would agree with Doyle that “uncertainty is an invitation to learn”—it is something that I do court throughout my life—I just find other ways to invite that instability. I can also empathize with the many people who’d just rather not have that much uncertainty in their own lives.

Who knows, perhaps being trans and having a gender history made me open to instabilities in ways that are much more difficult for some cis people—I’m amenable to that argument, although I imagine that the same could be said for any number of challenging experiences that cis people may have navigated in their own lives. There are many, many ways of introducing novelty and rejuvenation into our lives, and only some small fraction of them have to do with exploring our gender identity. It’s a good reminder that feminism, or gender theory for that matter, can’t and don’t necessarily have to speak to everything. I’m happy to embrace them in the struggle for my equality as a woman, but also to let them be when other philosophies better connect with other facets of my existence.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra