I am a little obsessed with communes. For years I’ve been constantly travelling, because job and rental markets have spread my network thin; I’m split across at least three cities, constantly struggling to be communal. I often wonder what it would be like to live in a small, intentional community, connected to others and to the earth, and loosened from alienation and from guilt. But, as Mattie Lubchansky explores in her new graphic novel Simplicity, there are limits to imagining a hopeful future as a small utopian enclave. The cops and the billionaires are here, and they need to be grappled with.

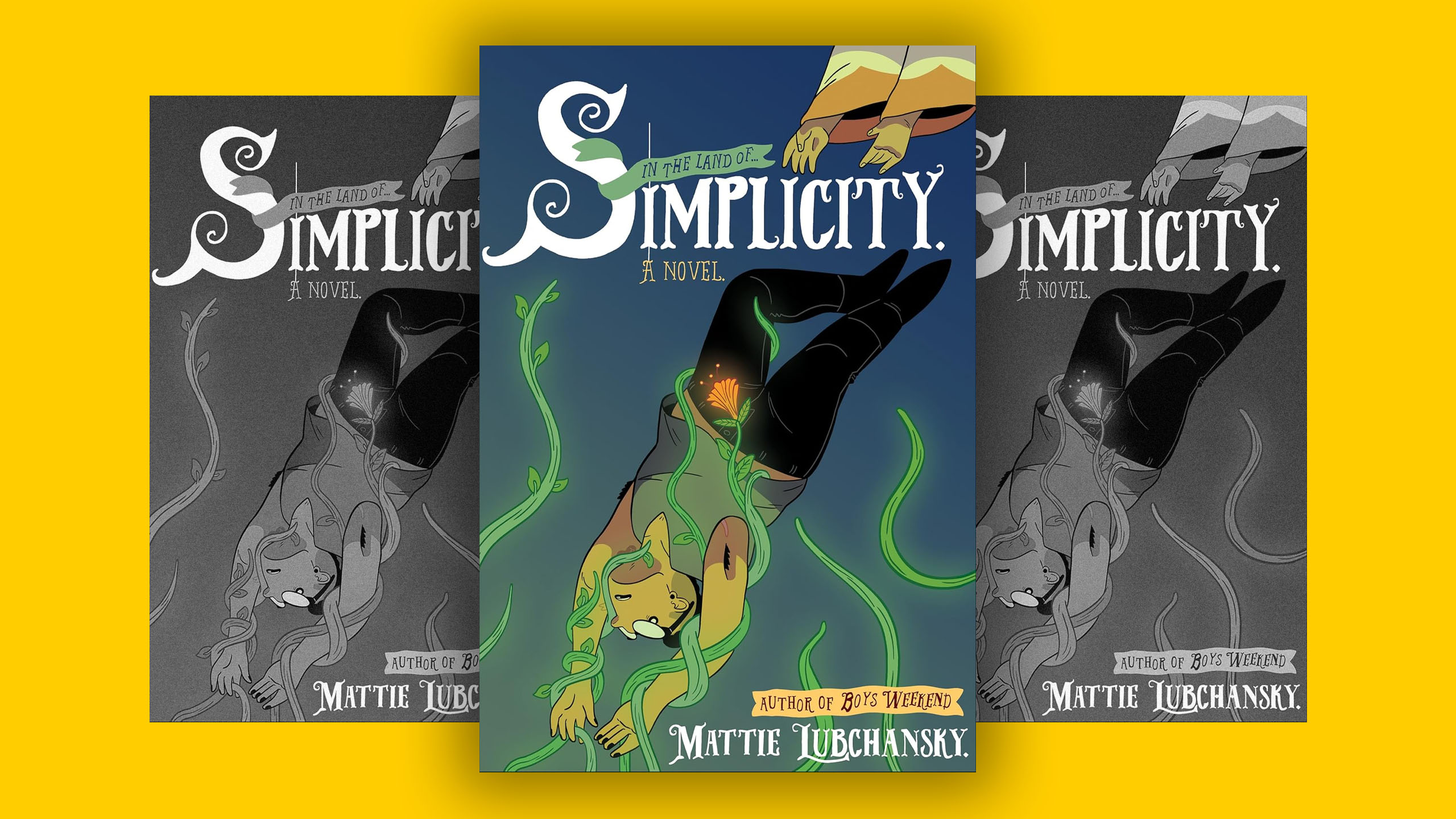

The past few years have proven Lubchansky to be a talented, prolific and politically focused cartoonist. She’s put out two full-length graphic novels in three years, while regularly releasing her signature four-panel cartoons on Patreon (after the demise of much-missed political cartoons and comics outlet The Nib). You’ll probably recognize her style if you’re on X or Bluesky: bodies and faces that are mostly realistic, but a little bubbled, a little pleasurably grotesque.

As Lubchansky recently told Xtra’s Jude Ellison S. Doyle, her political approach to the world and its horrors—such as the genocide in Gaza and the colonial history of the U.S.—is core to her artistic approach: “I think people’s inner lives are interesting too, and I’m interested in characters as characters, but to me, the thing that is interesting about making art and engaging with art is thinking about the world that I live in.” This structural vision and commitment is visible throughout her oeuvre, such as in The Antifa Super-Soldier Cookbook, a madcap satire of how the right conceives of antifascists. She’s also remained consistently interested in possible futures, particularly bad ones: she co-edited Flash Forward, a comics volume about “possible (and not-so-possible) tomorrows,” to which she contributed a comic about a nightmare labour dystopia where sleep can be staved off with medication.

Her first full-length graphic novel, 2023’s Boys Weekend, folded an intimate narrative about early transition into a blockbuster sci-fi/horror setting; it follows Sammie, the only trans attendee at a stag do, as they try to convince their oblivious friends that they’re all falling into the hands of bloodthirsty cultists. Simplicity, her second, shares some clear similarities with Boys Weekend. Both books are set in a near-future, mid-climate-change techno-nightmare, with ample opportunity for sight gags in the form of floating advertisements (“FISH SPOTTED IN HUDSON”). Both combine subtle emotional narratives centred on trans characters with bigger geopolitical emergencies. And in both, Lubchansky delights in drawing fat, slick, tentacular monsters, often owned by demented Bezos clones.

But while Boys Weekend is about a formative trip to hell, Simplicity is about a formative trip to somewhere peaceful and restorative. The new book is also significantly more focused on community. Simplicity takes place mainly in the 2080s: the U.S. has fallen, and New York State is now part of the unsecured “Exurb Zones,” outside of the militarily secured “New York City Administrative and Security Territory.” Lucius Pasternak, an anthropology scholar and trans man, has accepted a seemingly politically anodyne job; he’s joined the small commune of Simplicity for a few weeks, in order to survey its members and record their stories for a small history museum. The museum is being financed by NYC-AST’s richest real estate developer, which makes Lucius’s best friend wary—“you’re working for the Worm?”—but Lucius insists that it’s just a benign philanthropic venture.

Lucius is slowly charmed by the commune: its lack of surveillance, its communal decision-making, its non-competitive ethos, its fresh vegetables, its much-mythologized orgiastic rituals (which he watches anxiously from afar). At first, none of its residents agree to interviews, and it seems like his project will fail. But as he grows closer to Simplicity’s inhabitants, particularly Cleric Amity, the commune dwellers start to open up. Intimate oral histories are shared. Naked bodies, often visibly trans, become comfortingly familiar.

Yet Lucius’s dreams are being haunted by a terrifying creature—and, one day, a few weeks into Lucius’s residency, commune members start turning up dead.

Communes are perfect territory for speculative fiction. They feel a little dreamlike, a little unreal. Lucius himself says that Simplicity, by all stated rules, “shouldn’t exist.”

This spring, I visited one of the most famous anarchist communes in the world, Copenhagen’s Freetown Christiania. It began in a squatted military base in 1971 and managed to cling to life through sheer tenacity, good lawyers and its developing status as a tourist attraction. As of 2025, it houses about 1,000 people. In the commune’s bookshop, I found Postcards from Christiania, a book that details the history of the commune and its anonymous author’s experience living there.

The commune depicted in its pages is rich and multilayered: messy, politically incoherent, socially complicated and dotted with people who see it as a barely tolerable nuisance rather than a utopian community. So “it is all the more fantastical,” muses the author, “that we are still here and that the vast majority of those who come to visit like the vibe.”

Christiania is not much like Simplicity, formally—Simplicity is far outside the city, for one thing—but from having visited it, Simplicity’s setting felt familiar. There is a gentleness to many communes; a benevolent, expansive capacity to handle antagonism and bafflement. At the start of the book, Lucius is rootable but inflexible, somewhat of a coward, someone who shies away from intimacy and interrogation (which makes him the ideal patsy for a less-than-savoury project, to risk spoilers). The commune opens him up to new possibilities, flexible ways of thinking. This even manifests in beautiful, dreamlike visual sequences in which Lucius’s body shifts, becomes plantlike. He is changed by being part of a community that works like an organism.

But Simplicity is also consistently skeptical about visions of serene escape. At one point, Lucius watches a video of the founder of Simplicity, an ’80s hippie named Gerry, explaining his plans for the commune. He has a vision of a society blooming “here, away from the evils of humanity.” But Amity, at the climax of the novel, has come to a different view: “We thought we could show the world how to live … But we were just running, weren’t we? From what’s coming. […] We’re in the world. The choice has already been made for us.” The world is closing in on the commune, and Lucius and Amity know that hiding and pacifism are no longer meaningful options. Let’s just say the book does not end with peaceful negotiation.

Actually, I will spoil how Simplicity ends, but in an oblique way: it ends on an image of the surviving kooky, sweet denizens of the commune, with their children’s-book names (Amity Crown-Shy, Obedience Walking-Tree), being reconceived as an effective threat—as “terrorists,” “a bunch of communists, queers in weird robes … and worse!” Simplicity is a place of queer safety and peace for much of the novel, but this tongue-in-cheek ending suggests, perhaps, that there might be a more powerful model of safety than the commune outside the city. “Safety” might be the sound of someone insulting you as they’re running away.

Simplicity thus has some tension with queer and trans art that would stop at the beautiful sex scenes or the visionary conversations, that would accept withstanding the world rather than changing it. We don’t need to decide between those approaches, but Simplicity is symptomatic of how trans speculative fiction can push thinking about the future beyond the unpicking of homophobia and transphobia from the social fabric. It’s a counterpart, in that sense, to M.E. O’Brien and Eman Abdelhadi’s Everything for Everyone: An Oral History of the New York Commune, 2052–2072, which is also told through a series of fictional oral histories and imagines a successful communist revolution in the same territory as Simplicity’s militarized zone.

O’Brien and Abdelhadi’s fictional New York takes freedom of gender and sexuality as a given— an interesting and beautiful given, but also just one small aspect of an imagined world of communized care. In Simplicity, it’s obvious that the ills of the world would not be cleared up if just Lucius’s moments of gendered friction were eradicated. Nor do his moments of gendered ease among powerful people signal an end to the political system’s disdain for “queers in robes,” which rears its head the second those queers (or “pinkos”) become an inconvenience. Trans peace is good, but when received from those in power, it is only a kind of insulation. Simplicity asks: What if we can do better?

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra