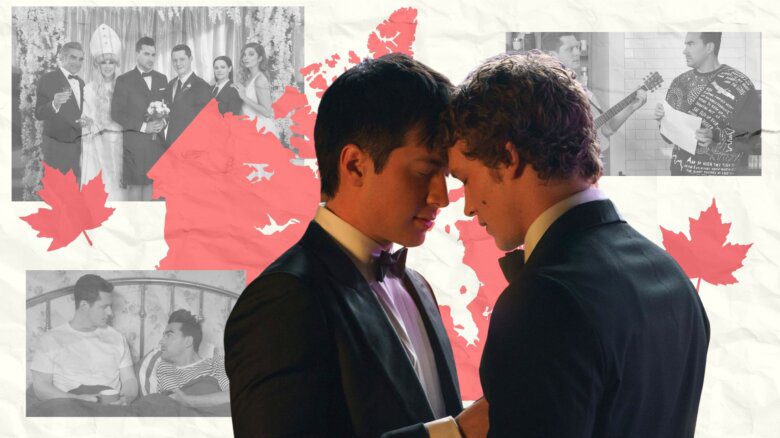

America in the 1950s was characterized by the drive for normalcy: following decades of back-to-back wars, suburbs began to halo big cities and highways began bisecting farmlands and villages, in attempts to establish a secure, homogenous way of life. It is this atmosphere of conventionality that stifles the central characters in Daniel Minahan’s film On Swift Horses, which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) this week. Set against the backdrop of mushroom clouds from nuclear tests sprouting in the desert, and the sights and sounds of a polite society that patronizes horse racetracks and casinos, On Swift Horses follows Muriel (Daisy Edgar Jones) and Julius (Jacob Elordi) as they negotiate how their respective homosexuality fits into the traditional expectations that envelop them.

At first glance, Muriel and Julius are the aspirational poster children for this idealized middle-class, suburban life: Muriel is a well-dressed wife, waitressing to save up for a place of their own with her loving husband Lee (Will Poulter), while Julius, Lee’s brother, is a tall, handsome soldier, fresh from serving in the Korean War. Yet, upon meeting for the first time, it is clear that they share a connection that is deeper than just being in-laws. They recognize, in each other, a secret bubbling beneath their primped and proper exteriors, though the nature of these secrets is not apparent at first. In a conventional romance, these three characters—the woman, her husband and his brother—would mark their own respective points in a love triangle. Yet in Minahan’s film, the threads that weave them together are less of lust and more of solidarity.

For Minahan, 1950s America marks yet another chapter of the country’s history that he has set out to capture on the screen. His very first writing credit, in 1996, was a collaboration with Canadian writer and director Mary Harron on the film I Shot Andy Warhol, which charts the sequence of events that led to the attempted murder of Andy Warhol in the 1960s. Directing episodes for shows like Hollywood, Fellow Travelers and the drama series Halston, Minahan has depicted the realities of queer people, whether those out in the spotlight of Hollywood’s Golden Age or hidden in the shadows during the Lavender Scare.

Based on Shannon Pufahl’s 2019 novel of the same name, On Swift Horses is a genre-bending film that investigates a psyche torn between expectation and authenticity. Speaking with Xtra over Zoom days after the world premiere of On Swift Horses at TIFF, Minahan dives deep into the themes that drew him to adapt the story.

You have mostly worked in television, directing episodes of Hollywood, Fellow Travelers and Halston. How does your approach to directing film differ from television?

The biggest difference is that when you’re directing a series, you engage with a piece that is already completely formed and has its own rules. It already has a cast and writers, and you come in and you do your best work, but also, you have to correspond with [the showrunners’] idea of the show. About ten years ago, I woke up one day and thought, “I’ve been doing everybody else’s homework, I need to find my own voice.” So I started reading books and trying to identify what it was that I wanted to do. After being in this industry for more than 20 years, I knew it had to feel significant and I also knew that it had to be a love story. So I feel like my return to features has been a gradual one, as I take responsibility and find my own voice again.

What is it specifically about Shannon Pufahl’s novel that inspired you?

It’s a novel with a lot of interiority: it felt completely new to me but also familiar. It has aspects of noir and melodrama, but [Pufahl] does it in her own way. It reminded me of books like [Gore Vidal’s] The City and the Pillar and [James Baldwin’s] Giovanni’s Room, and there are aspects of Patricia Highsmith’s writing too. I felt like the book was tipping its hat to a lot of queer literature and that was very interesting to me.

Will Poulter as Lee and Daisy Edgar Jones as Muriel in ‘On Swift Horses.’ Credit: Luc Montpelllier

The film is unique in its lack of clear antagonist: as Muriel’s husband and Julius’s brother, Lee would typically embody the opposition, yet he is continuously kind and empathetic to his loved ones. Can you talk about this choice?

In most films of this nature, where people are on a journey of self-discovery, there’s some baddie, the husband or a parent, who’s usually holding them back or disapproving. It felt like the thing that was keeping Muriel and Julius apart—what was keeping them from being their true selves—was the outside world and the kind of pressure that they put on themselves, as queer people, to be their authentic selves. Lee was so appealing to me because he’s so sympathetic. If Julius has a secret that he is discharged from the military, and Muriel has a secret that she’s gambling and experimenting sexually, Lee’s secret is that he knows everyone’s secret and turns a blind eye to it all because he wants so badly for them to be a family. And that was so unique to me. I didn’t want Lee to just be a cuckold. I talked with Will [Poulter] about it, and I couldn’t have found a better person for that role because he really gave Lee a lot of dignity.

The film has a sturdy sense of place and space: between the costumes at the horse racetracks to the design of the subdivision Muriel and Lee move to, how did you go about developing the visuals of the film?

I encouraged everyone, from the designers to the camera operators, to embrace the randomness of the locations—the casinos, the suburbs—to try to make them feel real, lived-in and messy. And specifically with Erin Magill, our production designer, we agreed on not having a controlled palette and, instead, film a full range of colour, as there would be in the real world. With our cinematographer, Luc Montpellier, we decided to express Muriel’s isolation through the housing development, so we filmed through different structures [like wall frames and beams] to give the sense that she’s trapped.

The romances in the film feel peripheral to the platonic relationship between Muriel and Julius, who share in their struggles with their sexual identity. Why is this kind of queer solidarity important to you?

This is the aspect about the novel that really appealed to me: their relationship was never explicit, it is implied that they have this deep affection for each other and these kinds of allies felt really familiar to me. I came of age during ACT UP in New York, so while men were dying around us, the people who were my main contacts and supports were lesbians who were running phone trees and other actions. If you think about the affection between Muriel and Julius, it is this idea that they recognize they’re never going to have a conventional relationship. They meet in the first 15 minutes of the film, and they’re never together again until the last quarter of it, but they still maintain a huge influence on each other. What they recognize in each other is that they’re both outsiders, gamblers and queer.

In a sense, while they recognize their commonalities, they also have a desire for the life the other has.

Muriel is in love with the idea of Julius’s freedom, and she blows up her life trying to achieve that. And Julius is really attracted to the idea of belonging somewhere, like Muriel does. As much as he knows he can’t live with his brother and his wife, he wants to find a place where he belongs.

They end up reconnecting through a “missed connections” board in a queer bar. Is this based on real events?

It’s interesting, because I did talk to Shannon to ask, “What do you know about this? Was this a thing in bars in San Diego?” And she said, “Oh, no, I just made that up.” But, at the end of the day, it’s what the board represents: this is how queer people found each other at the time, in queer spaces, in illegal bars like the one shown in the film. It helped dramatize the question: what is it like to miss someone and try to find them again?

On Swift Horses screens at TIFF 2024.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra