Imagine the calendar pages flying away, back to July 1991. It’s the summer between my Grade 11 and Grade 12 years of high school, after I have come out to all my friends and everyone at school, but just before I find the courage to tell my parents. I am sitting three inches away from the old television in the basement at midnight in Connecticut, my pulse racing. Something extraordinary is about to happen.

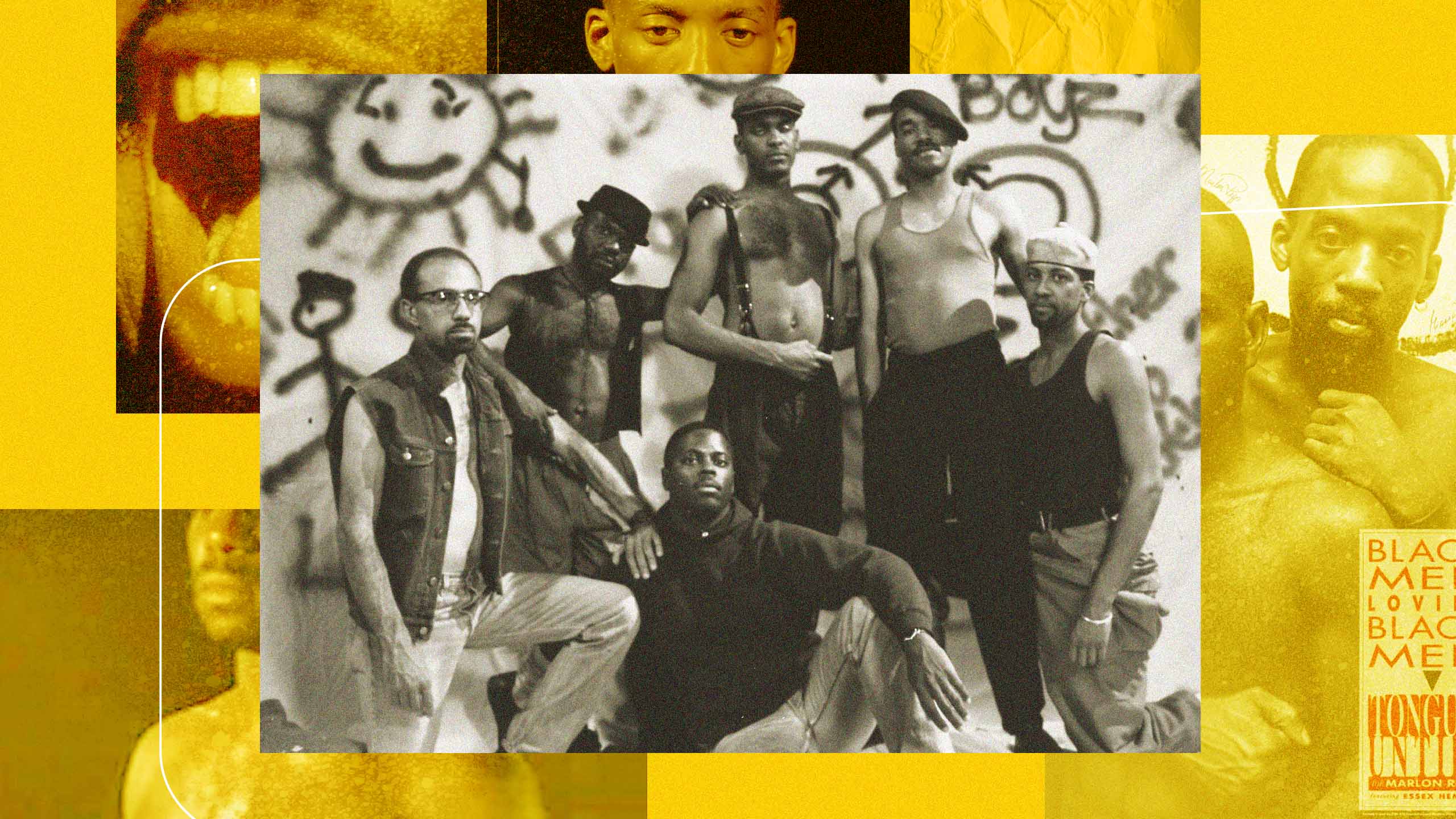

A new documentary is set to air on American public television’s PBS network, as part of their POV series, and I am so excited about it that I’m tingling. It is being aired at midnight because of a massive hue and cry from the reactionary right-wing conservative machine—they are really, really mad because the film Tongues Untied by artist and educator Marlon Riggs is a poetic, erotic, transcendent film about Black queer men. They make such a fuss that although the film will eventually be recognized as the masterpiece it clearly is (and available to stream for free with a library card on Kanopy), even though we are very obviously in the era of sanitizing and repackaging Black queer culture for the titillation of the white gaze (greetings to Madonna and Mapplethorpe, among others), only 29 stations in the 50 major PBS markets will air the film at all, even at midnight.

(The late ’80s and early ’90s were a busy time for fundamentalist fuckheads. Two years earlier, they’d started hounding the National Endowment for the Arts about photos by Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe, and then moved on to defunding a group of queer performance artists who came to be known as the NEA Four by ramming an “obscenity clause” through the U.S. Congress, hoping to prevent public money from being used for any kind of queer-themed art.)

Cut to 16-year-old me in 1991. At 11:59, I turn the television on, at the lowest possible volume. At midnight on the stroke, a content advisory plays and then a chorus of voices begin to chant: “Brother to brother, brother to brother. Brother to brother, brother to brother,” like a heartbeat, like a warding, like a warning. Despite the fact that I am a white suburban teenage queer in ’80s talk-show-host eyeglasses and could not have been more protected or separated from the lives shown in Tongues Untied, I am riveted for the next hour.

Tongues Untied is a collage: poetry and commentary mixed with remembrance and reflection, laid over visual representations of Black gay men’s lives in late ’80s San Francisco. Within the first two minutes, we see a sun-soaked picnic and a police raid; the distinctive eye-gaze of cruising and the familiar bug-gaze of helmeted riot police, anonymized behind their mirrored shades, while the chorus of performance poetry collective Cinque (Essex Hemphill, Larry Duckett and Wayson Jones) recite aloud: “As I have learned to mute my cries of anguish, so I have learned to squelch my exclamations of joy.” For the first of maybe a hundred times across the hour, I regret not having paper and a pen to take notes.

“I wonder whether it seems strange to an audience in 2024 that an at-the-time 16-year-old white Jewish junior-ranger butch dyke would have been so excited for this film about Black queer men.”

Tongues Untied is a synergy of geniuses—Riggs and Hemphill most specifically, with the hungry ghost of Joseph Beam to supervise—and every part of the visuals elevates the words, and vice versa. The film is immediate, intimate and electric, using small vignettes and broad allegory to welcome the viewer into Riggs’s emotional landscape. Looking back, nothing about the film was familiar in the specifics, and yet the sense of queer longing for connection, for community and for safety were so redolent with emotional truth that it rang all the bells in my heart. I, too, wanted those things. I, too, wanted to be seen as real, as hot, as a part of something even though that something was also dangerous.

I wonder whether it seems strange to an audience in 2024 that an at-the-time 16-year-old white Jewish junior-ranger butch dyke would have been so excited for this film about Black queer men, the AIDS crisis, being targeted by police, finding joy in all the crevices overlooked by mainstream. But these were the days where the most recognizable gay symbol was the pink triangle (before Gil Baker’s rainbow flag was popularly adopted, and then supplanted by Daniel Quasar’s version); the days when saying “gay and lesbian” instead of just “gay” was considered progressive and all the rest of the letters were still silent. Representation of any portion of queer experience or identity was so rare, and typically so unkind, that the idea of watching a film about gay people that had also been made by gay people was enough to ring every bell in my feelings. I was too young for bars, and awkward besides, and so I read a lot. I watched a lot of films. I pored over the lyrics of singers rumoured to be gay, hearing an implied lesbian partner in every lyric Melissa Etheridge growled and danced a happy little dance listening to Erasure when “Witch in the Ditch” came on and they sang, “Yes it was you, my love/ That made me turn around/ Yes it was you, Mein Herr/ That turned me upside down.”

Whatever there was, I wanted it. And I have pretty much carried on as I started, always keen for new flavours of queer art, always hungry for old vines to bear new fruit. Tongues Untied features work and ideas from the book In the Life, edited by Joseph Beam, who then started Brother to Brother, the anthology intended as a follow-up, but died before he could finish. It was taken over by Essex Hemphill and (in a surprising twist) Beam’s mother, Dorothy Beam, who continued his work, tended to his papers and even invited Hemphill to live in their home while they finished work on Brother to Brother. Riggs went on to make several more movies before he died, also of complications arising from AIDS, in 1994, including the absolutely essential documentary Ethnic Notions, which remains a gold standard in understanding racist iconography from the Jim Crow era of the United States and the ways those tropes continue to be reanimated, subtly or overtly.

In the sunshine of Tongues Untied, Black queer work bloomed along the path it made. The anthology Shade, a collection of fiction by gay men of African descent, was published and won awards, Samuel R. Delany (a notable writer of science fiction) published more of his overtly queer work, including his memoir, The Motion of Light in Water, and James Earl Hardy started his B-Boy Blues series featuring the love story of Mitchell and Raheim. In the same era, we got Emanuel Xavier’s exceptional Pier Queen, a book of poetry by a queer Latinx author that overlaps thematically and in tone; and the documentary film Paris Is Burning introduced a wide swath of the American public to ballroom culture, through the lens of a white woman who largely peaked when documenting the real lives of the NYC ballroom scene and seems to have been coasting on that work since. This work is both difficult because many subjects of the documentary are now dead from AIDS and also invaluable (because many subjects of the documentary are now dead from AIDS).

Many of the artists from this era are dead now, from AIDS, cancer or just being old and tired and injured in body and spirit; the living ones range from their late 50s to 80s and beyond. The art they made in the ’80s and ’90s and even into the early 2000s has been largely overwhelmed by an avalanche of newer, shinier, slicker, work with LGBTQ2S+ themes, which, while I enjoy a lot of it, has largely been passed through many filters of mainstream money and therefore mainstream sensibility. Things are shinier and production values have improved, but also compromises abound now that profit (and straight people) have to be considered.

For example, look at the distance between the beautiful little movie Brother Outsider from 2003, another small passion project funded largely by public television, and last year’s Rustin, with a $10 million budget that took the Obamas to get made (their production company, Higher Ground, produced it for Netflix). Both films are about the overlooked legacy of Black gay civil rights leader Bayard Rustin. In the latter, I can feel how much the movie wants people to love Rustin even though he was gay; in the former, my overwhelming experience was that the filmmakers had chosen to feature Rustin exactly because he was gay. And the truth is, as much as I enjoy the very talented Colman Domingo, who just got an Oscar nomination for playing Rustin in the Netflix film, I do not enjoy the experience of being a secondary audience for a film that should be of primary importance to me and my queer peers.

As we have traded up in visibility, projects with queer themes are now made by hundreds of people, all hoping it will be a stepping stone to a bigger, fancier project. I fear that some of the connection and tenderness that marked moments like Tongues Untied have been lost—the clarity of Marlon Riggs’s vision, the tenderness of him and his friends and lovers collaborating on a piece of work that they knew would outlive most of them, allowing themselves to be honest and messy and sincere in public, where people could see. Honestly, that feeling may be what I love the most about queer work from the late ’80s and early ’90s, and the very thing that Tongues Untied has in abundance. The film is not just a collection of facts, it’s an artifact from when queer artists had just begun to tell the truth. If you feel being queer is as much a political orientation as it is a sexual one, if you are exhausted by late-stage capitalism and pinkwashing and the demands of respectability, if you—you personally—are ready for un-straightened stories of queer power, then start with Tongues Untied.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra