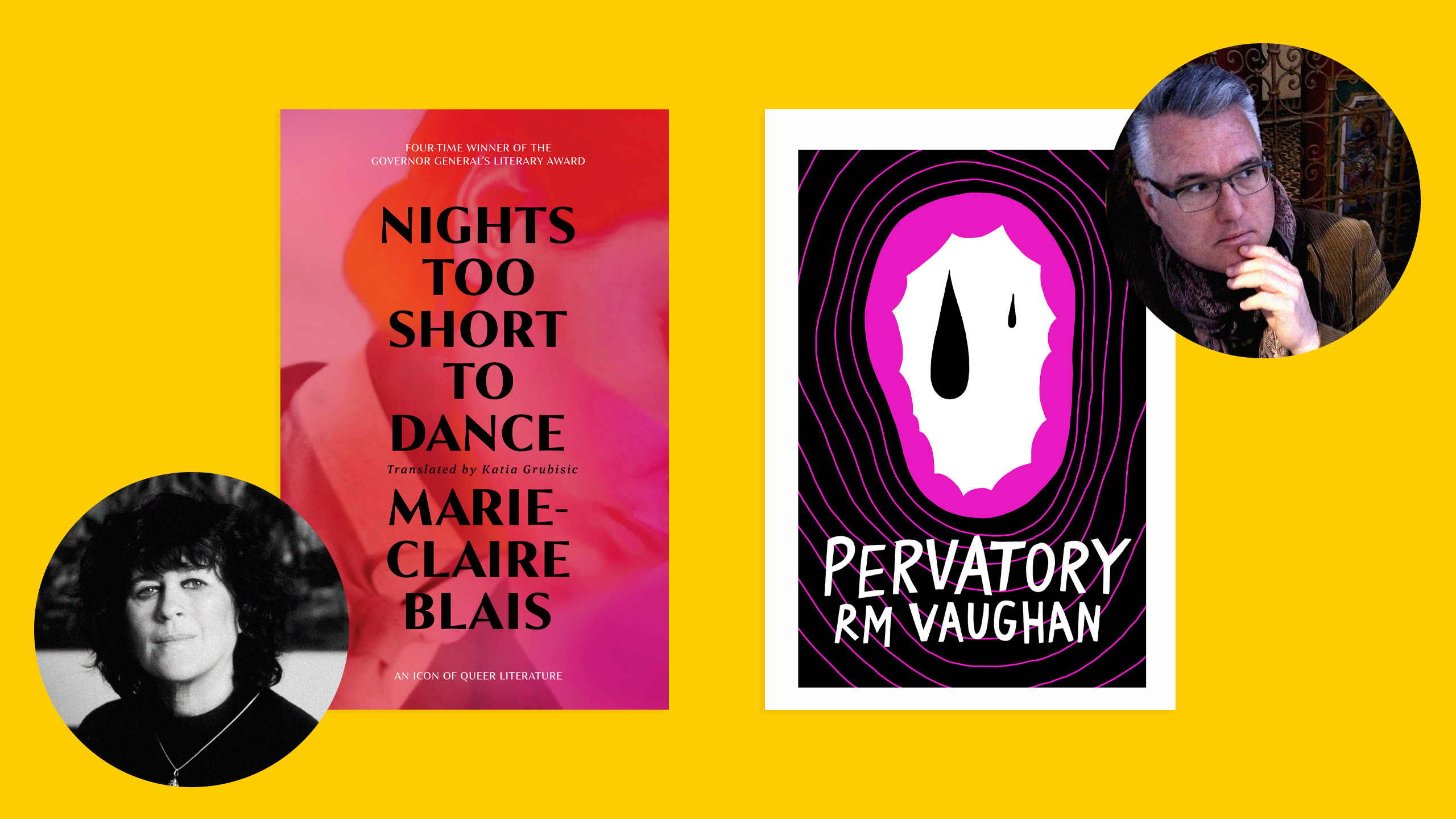

Two books are out this month by queer Canadian legends who left us during the pandemic. Marie-Claire Blais was one of Quebec’s most famous writers, whose social novels played with form, while RM Vaughan’s pithy and personal compositions offered off-kilter critiques of the modern world. The two couldn’t have been more different in style and content, yet both left an indelible imprint on queer literature in Canada. These two new posthumous works speak proudly of their legacies.

Pervatory by RM Vaughan

After RM Vaughan’s untimely death in October 2020, his brother asked two of Vaughan’s longtime friends—writer Jared Mitchell and poet Jeramy Dodds—to be literary executors, and decide what to do with the notorious writer’s creative effects. Among the items left behind were a series of poems, a few unfinished crafts and an unedited manuscript about the sexual adventures of a Canadian expat living in Berlin.

“I loved it,” says Mitchell, Vaughan’s close friend for over 20 years, referring to the manuscript. “I kind of tucked into it because I didn’t know it existed. So, to come across it and read it—it was like Richard was back in the room with me.”

A writer, journalist and art critic for over 30 years, Vaughan (Richard, to his friends) was well known in Canadian art and literary circles for his social and cultural commentary, as well as his acerbic wit. He was a darkly funny man—honest, sardonic, contrarian. A frequent contributor to Xtra, he authored and edited more than 30 books during his lifetime and was a trailblazer for LGBTQ2S+ literature and theatre. His sudden disappearance, and death by suicide, at 55 left the queer Canlit community reeling.

Once Mitchell realized that his departed friend had intended to publish this work, he took the manuscript to Coach House Books and editor Alana Wilcox, a friend of Vaughan’s who had worked with him on previous titles. Together with Dodds, the three got the text to a place where it could be considered finished. “It was disjointed at points, sometimes requiring more explanation,” says Mitchell. “We all agreed that we were not in a position to do a pastiche of Richard Vaughan, so the only way we could solve any issue was to cut and reorder. All the words in the book are Richard’s.”

A concise novel told in short chapters, Pervatory tells the story of Martin Murray Heather, a rather bored and disillusioned middle-aged gay man who decides to leave his life and community in Toronto and move to Berlin to drink and fuck himself to death. Berlin, to Martin, represents true abandon, a place where “so very little counts,” perfect for “the resignation years.” For Martin has a chip on his shoulder. A skilled writer and journalist, he feels unloved by the city that bore him. And even though the people he meets in Berlin’s bars and sex clubs all tell him how wonderful they think Canada is, he can’t see his life there as anything but a disappointment. Toronto, he believes, is a city overly concerned with status and “where failure is judged more harshly because the very idea of accomplishment is itself second-hand.”

Abroad, however, Martin has nothing to prove to anyone. “In Berlin it is okay for me to be past thirty-five and still be sexual, to be fat and still be sexual, to be poor—everybody is poor here —and still be sexual, to be a nobody and still be sexual. Because in Berlin to not be sexual, right up until you die, is breaking the rules.” Could this city be the beginning of Martin’s next act?

We follow our hero as he hops aboard the U-Bahn to experience the endless sexual smorgasbord that Berlin has to offer. The book is frank and explicit in its depictions of sex; it’s filled with dark humour too (Martin casts a spell on a screaming kid who lives above him by setting a trap with tiny pyramids of salt in the building’s lobby). One immediately recognizes the cantankerous Vaughan in Martin, as our protagonist contemplates sex, death, children, love, art, fame and family. On a night out at a fetish bar, he meets Alexandar, a dom top who becomes Martin’s “Berlin project” and begins to untangle every twisted knot inside of him. The two end up having an intense affair.

We know, however, from the beginning of the book, that Martin is recounting this story from the inside of a mental health facility, looking back on his time with Alexandar and the actions that brought him to his incarceration. As the book progresses, the story deftly moves away from being wry and lighthearted to dark and, and times, disturbing. It all ends with a bit of a surprise. “What Richard might have been aiming at is that crossover point between our longing and the mundane world, and the extremes our longing could be,” Mitchell surmises. “Richard could be an extreme guy in terms of his loves and hates.”

Reading this book and knowing the author’s fate, it’s hard not to wonder about the state Vaughan might have been in while writing it. Although sarcastic and flippant at times, there is an undercurrent of loneliness and sadness that runs through the text. “Because of the circumstances of Richard’s death, I think we start to [ask], is this an apologia?” Mitchell says. “Is this an explanation? Is this a philosophical culmination? Are there clues in here as to why he committed suicide? … I don’t think so. But just knowing that he died, while writing this, I think everybody wants to know if there are clues in here. I don’t think there are.”

As someone who also knew the author personally, I too found myself missing my old friend while reading these pages. The book is smart and edgy, filled with doubt, wonder, sex, fear, suppressed rage and a passion for living. I wish he was still around so we could go for a beer and I could ask him about it.

Nights Too Short to Dance by Marie-Claire Blais

Not many English-speaking North Americans know about the incredible career of Marie-Claire Blais. The author of more than 30 novels and numerous plays—and the winner of dozens of awards, including the Prix Médicis and four Governor General’s Literary Awards—Blais broke on to the scene in 1959 at the age of 20 with La Belle Bête, a gruesome fable about a dysfunctional family that sent shockwaves through Quebec when it was first published. Often compared to Virginia Woolf, Blais was frequently listed alongside Margaret Atwood as one of Canada’s best writers. She died of an undisclosed cause in November 2021 at the age of 82.

“She is much more known among the formalists, or neo-formalists, because of the way she writes,” says writer Katia Grubisic. In formalism, the visual components of a work—the way it is made and its form—are the most important aspects. Grubisic recently translated Blais’s novel Un cœur habité de mille voix into English. The posthumous translation, Nights Too Short to Dance, is out this month from Second Story Press, with Grubisic again translating. “She has this relentless way of writing,” Grubisic says. “You kind of have to go into it knowing what you’re getting into.”

Nights Too Short to Dance tells the story of René, a queer- and women’s rights-activist in his 90s, recovering at home from an illness. From the perch of his bed, he is reminiscing about his life, his youth and the evenings in which he would play piano at a nightclub and flirt and with the unhappily married women who would come up to him. His nurse, Olga—a Russian woman he has hired to take care of his needs—continues to misgender him. “Don’t call me Madame,” René says. “Don’t forget I’m a man, I look like a woman.” His friend Louise is also with him. A former lover, Louise is helping René get dressed for an afternoon of visits from old friends. And visit they do, in multiple ways, as the novel weaves in and out and back and forth over more than 50 years.

There is Doudouline, the musician, and her lover, Polydor. There is Gérard the second, who took her name from Gérard the first, after the first was lost to drugs and alcohol. There is Johnie, the intellectual, and Lila, René’s “brother,” who is working to save young gay men from HIV. Finally, there is L’Abeille, the painter, whose crumbling house they would all talk and drink and smoke and sleep in. All of René’s queer women friends chose new names for themselves as they came of age, and they express gratitude to him for his years of activism. In fact, he is so much a part of their lives that their stories cannot be extracted from his own. It all comes out in a beautiful cacophony: love, fidelity, marriage, resistance, sex, aging, death.

One of the hallmarks of Blais’s work is the elliptical sentence, and like many of her other books, Nights is written in a stream-of-consciousness style. There are no paragraphs in this book, and few sentences. The comma is working overtime, and the result can sometimes feel like swimming in a chorus of words, not always being sure as to what is being communicated by who and to whom. Sentences meander, perspectives shift, dialogue is unattributed and there are no benchmarks to keep your head above water. Blais makes you work for your treat.

Translator Katia Grubisic. Credit: P. Seib

As for Grubisic, whose job as translator is to interpret a text for a new audience, not having Blais around to answer her questions was challenging. “Often in French, because of the way agreements work, you don’t have the pronoun. It doesn’t necessarily belong to the person, but to the object. And so, I had these moments of ‘Well, which way should we leave it here?’” What complicated things further for Grubisic was that not only did Olga misgender René, but Blais also genders René differently throughout the book, using both he and she in whichever way suited her.

This is Grubisic’s second translation of a book by Blais, after Songs for Angel in 2021. “For the first translation, she and I were able to correspond. She was super generous and hands-off about everything.” Sometimes, Grubisic would notice a discrepancy in the text and bring it to Blais. “She’d be like, ‘Do whatever you want.’ So, I was pretty much left to my own devices, although she would approve the final version.” With this last, posthumous translation, Grubesic was surprised at how bereft she felt while working on it. “Her absence was a presence throughout the translation, if that makes sense. Like there was this hole in how I was approaching it.”

In terms of logistics, Grubisic was able to get most of her questions answered by Blais’s longtime editor at Les Éditions du Boréal, Jean Bernier. Most of her questions were around word choice and tone, to make sure that everything was faithful to Blais’s point of view. “He was instrumental in terms of making me feel that she was still there in her thought process.… The infrastructure was already there; all I had to do was furnish it.”

Grubisic does an amazing job with the translation, capturing the youthfulness of the chorus of characters and Rene’s passionate digressions. Make no mistake, though, the book still is a whirlwind and can be challenging to read at times. My recommendation, if you want to discover Blais’s work, would be to not overthink it (and least with the first reading) and sit back and enjoy the ride.

Blais left one last work before she passed. Augustino ou l’illumination was a work-in-progress that her publisher Boréal released as is in 2022. The work ends mid-sentence on the page, incomplete. Grubisic translated a short excerpt of it for carte blanche magazine this summer, and hopes to translate the rest one day. “I’m making a presumption, but we often look for closure in a way that’s not necessary, or maybe even healthy. I think there would be a lot of value in publishing something, or reading something, that’s unfinished. I think it would still be a book.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra