Brandon Wolf grew up in a small town in Oregon—a community so rural they held “Drive Your Tractor to School Day.” But being both Black and queer, he felt like an outsider and was often reminded of it, like the time he was called the N-word as a child and when classmates and community members held an anti-gay rally at his high school.

In search of a more welcoming home, like many young queer people from small towns, Wolf found solace elsewhere: the diverse city of Orlando, Florida. It was his home for eight years before, tragically, on June 12, 2016, his sense of security was shattered when he went to Pulse nightclub along with his best friend Drew, and Drew’s boyfriend, Juan. They were regular patrons of the popular club, going a few times a month.

What started as an ordinary night transformed into an unimaginable tragedy as 49 people were killed within the club’s walls, including Drew and Juan.

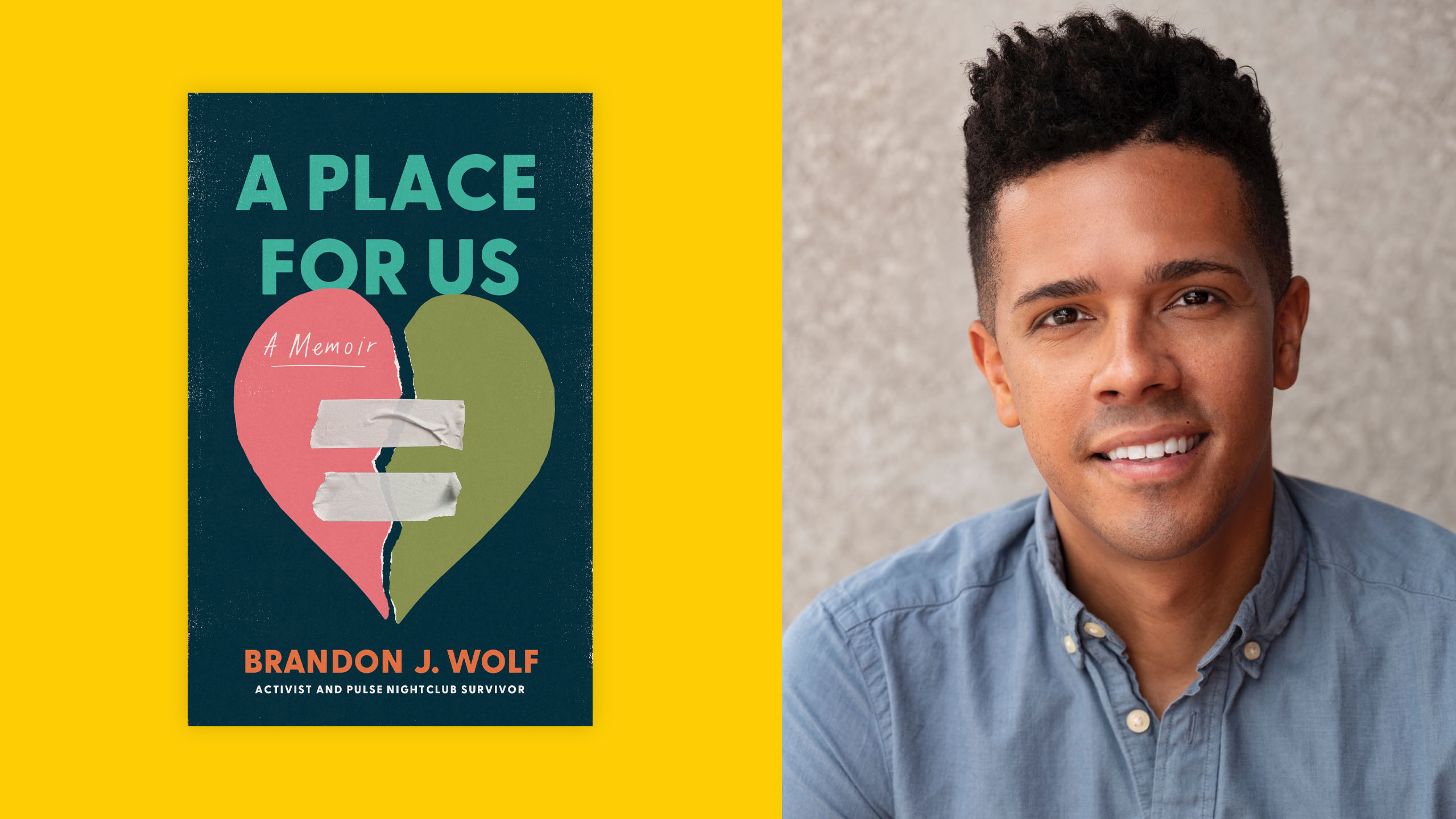

In his debut memoir, A Place for Us: A Memoir, Wolf takes us on a journey—recounting his childhood, his search for a community after leaving Oregon, the grief of losing his chosen family and the impacts of gun violence.

Now the press secretary for the LGBTQ2S+ advocacy group Equality Florida, Wolf’s vulnerable storytelling acknowledges the depths of his sorrow while also sharing a message of hope and optimism. He demonstrates his new purpose of channelling grief into a force for change.

You wrote about how Drew taught you a different way to love, which is relatable for a lot of queer people, depending on their circumstances growing up. Tell me more about how he showed you love in a way you didn’t think was possible.

Love, as a queer person, is such a complicated topic, because for our entire existence, our love has been demonized, dehumanized, hypersexualized. Our love has been made to feel shameful. For that reason, our relationship with love, people, compassion and empathy is all very complicated. Meeting Drew was a revelation for me because he was one of the first people I met who was queer and mixed race and just so confident, unashamed and unapologetic. He’s one of the first people who taught me unconditional love. No matter how many times I got angry or started a fight, he was there. He was going to remind me every single time that our love was unbreakable.

As a young queer person of colour, that was just not something I understood. It’s not something I knew how to process, accept or even believed that I deserved.

So much of our [community’s] complicated relationship with love is about self-loathing; it’s about internalized homophobia and hate that we have. Drew unapologetically loving me, flaws and all, challenged me to learn to love myself in the same way.

How did you, Drew and Juan end up at Pulse that night in June 2016?

There’s a reason that I titled [the chapter about the night at Pulse] “The Last Normal Day,” because that’s in many ways what this community calls June 12, 2016. Everything about it was normal.

I was going through a breakup at the time, and was struggling with a champagne hangover and folding socks and underwear on the couch.

My ex at the time, Eric, asked if I would go get a drink with him. That was a terrible idea because when you’re freshly out of a breakup, the last thing you need to do is be consuming alcohol in a social setting with your ex. But I was being a hopeless romantic and thinking, “This is my chance, but I need backup.” So, I did what any normal friend would do: I texted Drew and Juan and asked if they would be my backups.

They got to my apartment. We listened to our usual playlist. We made drinks, ordered an Uber and went to Pulse, a place we’d been to hundreds of times before.

I tell people that Pulse is one of the first places I ever held hands with someone that I had a crush on without looking over my shoulder first. It’s one of the first places I could wear skinny jeans without worrying what people would call me. It was a place to exhale where the music, fog machines and cocktails dared you to be a whole human being. Everything about that night was that: normal.

You start the book with the story of your mom’s death from cancer when you were 11 years old. You described a strong scent of bleach drifting through the air of the hospital. Tell us about that moment.

When I started to write the book, I started with just vignettes, these moments in life that are so vivid they stick with you. They appear in dreams, even if you’re dreaming about something else, and that’s one of them. My mom was the first ally I ever had in my life. It was just me and her for many years. I remember how jealous I was when she got married because I thought that might mean I’d have to share her with other people. I remember how painful it was the day she passed away. The smell of bleach in the hallway [of the hospital], the puffy eyes of my family members. I talk about looking through that glass in a hospital room door and the way it has those criss-crossed wires in it that makes you feel like you’re trapped in a prison. I also wanted to tie the way that death imprints itself on your mind to stories of loss around Pulse. One of the themes I wanted people to take away was that all of these moments leave scars, and there’s no way you can erase them. You just learn to grow around them.

What were some of those environmental memories of Pulse?

One of the themes that jumped out at me when I was writing the proposal for this book was the fact that I could still smell both experiences. In my nightmares I could smell it. I could still smell the gun’s smoke and the blood. I remember this tangy cocktail in the air of Pulse in the same way that I can still smell the bleach from the linens in the hospital when my mom died. The sound of the oxygen machine that was keeping her alive is so vivid for me the same way the sound of an assault rifle is so vivid. The way her hands looked against the bed is so vivid to me in the way that I can still remember distinctly what the poster above the urinal in the bathroom that I was hiding in looked like.

Maybe it’s driven by trauma, but there’s so much about those experiences that are parallel because they’re marked by these heightened extreme senses you can’t shake.

At several points throughout the book, there are traumatic experiences: my mom dying, a sexual assault in college, Pulse nightclub. Every single one of them is marked by intense senses that are more than just “here’s what was happening,” but rather, “this is what it felt like, this is what it smelled like, this is what it sounded like.” I hoped in that way that I could speak to people who have experienced trauma as well, telling them those things are valid, and the fact that they haunt you is real, and it’s part of our process to work through.

You wrote about the guilt you felt later about asking Drew and Juan to go with you to the club. Were you concerned about being that vulnerable in your memoir?

I really wrestled with whether or not to include that particular story, because it’s very vulnerable. It is something that I carry with me and struggle with to this day, that my therapist and I talk about a lot. This idea of feeling guilty that you’re responsible for what happened to other people.

I’ve had experiences where that has popped up around anniversary time, and it’s been very triggering for me. I struggled a lot with whether or not that’s a story I should put in this book, and started to fall into the trap of putting it through a cheesecloth: “What if right-wing people read this? Are they going to use it as a weapon?”

Then, as I was piecing the book together, that was a hole where something was clearly missing. It was something that was there, in the fabric of the stories, it was there in the tension of the pages, but I wasn’t calling it out. It felt like I was lying. It felt like I was not telling the truth about who I was and my journey. I talked a lot about healing and self-care, and all of that felt like a lie if I wasn’t being honest about the weight that I was carrying.

So, I sat down, and I said to myself, “You just have to write it.”

I realized I’ve survived worse than some right-wing trolls on Twitter, I can handle that. But what I can’t handle is putting a book into the world that is incomplete or inauthentic.

You talk a lot about your intersectional identities and the way our struggles are intersectional. How does that theme carry through the book and the advocacy you do today?

There have been so many points over the last seven years at which I could have sat down and written a book, but it was the murder of George Floyd that finally propelled me to take that step. I talked a little bit in the book about this moment I had where I was feeling immense guilt in the wake of his murder, and I talked to my boss, who is a queer Black woman who grew up in a rural community, about it, so she’s got a lot of parallels with my experience. She said, “What are you carrying?” And I said, “I’m carrying guilt, and I don’t know why. I don’t know how to articulate why I’m carrying that guilt.”

As we started talking about it, I realized it was because I felt like I was betraying the Black community in that I didn’t understand how it felt to be Black in that moment. I didn’t understand how it felt to carry the generational trauma and pain of what was happening. From an empathetic, compassionate standpoint, I wanted to. But I felt isolated from it because I didn’t really understand what people were going through. I didn’t know how to articulate that.

She said to me, “Severing you from your identity, making you feel isolated from parts of who you are, is a function of white supremacy. By sapping you of your ability to tap into community power, it is a way of disempowering you as an individual.’’

That was my “a-ha” moment. I said, “I have to write it.” It’s not a book about Pulse or being queer, it’s a book about being queer and Black, and also half white, and learning to navigate those things and dealing with all the weight of what the world puts on your shoulders. I need to be honest and authentic about all of it because someone out there is living a similar path and they don’t believe the world has space for them either. They need to hear that they have every tool in their toolbox necessary to go out and blaze a trail.

Intersectionality is the thing that finally became a catalyst for writing the book. It is a theme that stretches through from beginning to end. It is the thing that has animated all the work I’ve done over the last seven years.

You wrote that purpose is a powerful antidote to grief. What’s your purpose today?

Six days after the shooting, we had that funeral service for Drew. And on that day, I made a promise to him that I would never stop fighting for a world that he would be proud of.

That has become my purpose over the last seven years, to relentlessly, unapologetically, unashamedly advocate for a world not just that Drew would be proud of, but a world that all of us can be proud of. I fundamentally believe that world is possible.

Every time I travel this country and I meet new people, I am reminded that there are far more of us who believe in treating each other with dignity and respect in kindness and compassion than those who don’t.

Do you believe you will see a world Drew can be proud of in your lifetime?

I’ve come to terms with the fact that I may not see all the fruits of my labour. But I take comfort in the knowledge that we are creating moments of oasis along the way. We’re creating opportunities for queer young people to be able to exhale, to wear that skinny pair of jeans without being afraid of what someone might call them or to hold hands with someone they have a crush on without worrying who might be watching. I take great comfort in knowing that we are creating some of that safety and belonging along the way. I also take comfort in knowing that we’re setting up the next generation to finish the job that we started.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra