At 76, Miss Major Griffin-Gracy is many things to many people. She is a force: a tireless change-maker and inspiration to a generation of trans people. She has lived an incredible life, having been at so many key moments in history, from Stonewall in the ’60s, to AIDS activism in the ’80s and ’90s, to trans justice and abolition work in the last 20 years. She is connected to key figures in the LGBTQ2S+ activist canon, including her elder, Marsha P. Johnson, and Storm Delavarie, host of the Jewel Box Revue, where she performed. I first heard of Miss Major at a party in T’karonto in the late 2000s. Sex work activist and abolitionist Chanelle Gallant had just gotten back from spending time with Miss Major in California and wanted to help document her incredible life. We talked about what might be possible, and dreamed into a time when Miss Major could be celebrated for her incredible contribution to justice movements of our lifetime.

This was several years before the incomparable 2015 film Major!, directed by Annalise Ophelian, which chronicled Miss Major’s involvement in key queer and trans liberation movements. I was working with the Prisoners’ Justice Film Festival and teaching a prison abolition course at York University, and we screened Major! at the festival in London, Ontario, that year. Following the film, we had a remote conversation with Miss Major and Ophelian. It was amazing to witness the audience full of budding abolitionists engaging with this longtime prisoner-justice organizer, talking through trans justice and abolition.

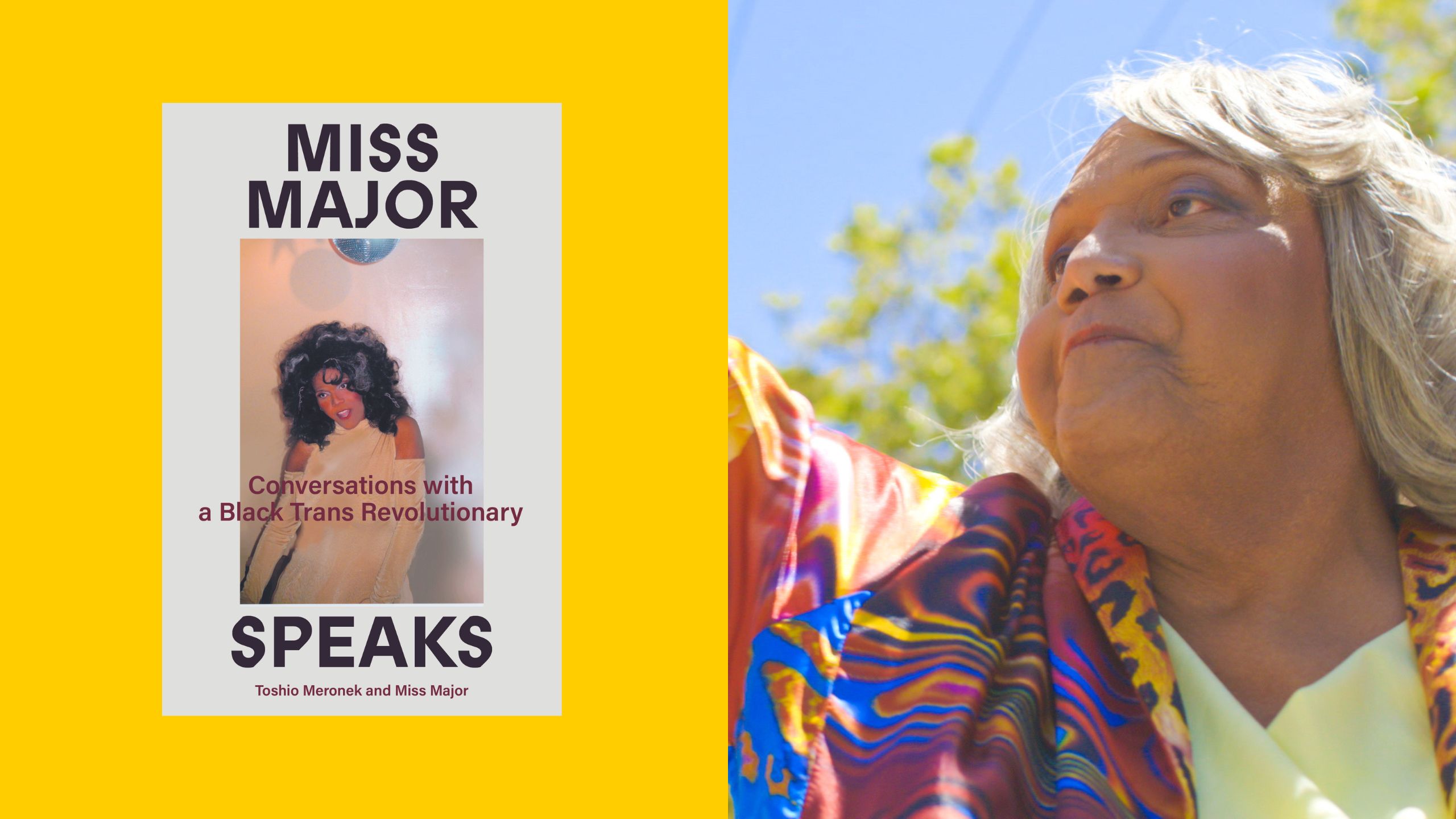

In 2020 I was invited to be in conversation with Miss Major for the University of Victoria’s Moving Trans History Forward conference, held in conjunction with the Trans Archives there. I spoke with both Miss Major and Vancouver-based Black trans activist Kelendria Nation. The conversation was quite magical—three Black trans organizers together, speaking about love, justice and change-making. Together, we prefigured the communities we wanted to livin within, while also reflecting on the past. Speaking with Miss Major was life-giving, her candid approach refreshing. I was thrilled to hear about Miss Major Speaks: Conversations with a Black Trans Revolutionary, a new book by Miss Major and Toshio Meronek. It was exciting to be able to sit down with Miss Major through reading the book and dive deep into stories about her life, organizing and family-building across Turtle Island.

Miss Major Speaks is part biography, part interview and is full of Miss Major spitting truths and laying it down like it is. As an abolitionist, organizer, HIV worker, harm reduction supporter and parent, Miss Major is the elder so many of us have looked to. “Miss Major Griffin-Gracy is a veteran of the infamous Stonewall Riots, a former sex worker and a transgender elder and activist who has survived Bellevue psychiatric hospital, Attica Prison, the HIV/AIDS crisis and a world that white supremacy has built,” according to her publisher. “She has shared tips with other sex workers in the nascent drag ball scene of the late 1960s, and helped found one of America’s first needle exchange clinics from the back of her van.”

In Miss Major Speaks, we get a behind-the-scenes story of Miss Major’s life. The book starts with a broad overview of her early life by her former assistant Toshio Meronek. The book then shifts into interview mode, and we get to explore chapters of Miss Major discussing everything from the Jewel Box Revue and working with Storme Delavarie, a Black transmasculine MC and performer who fronted the trans showcase, and others there, to early days in HIV care, to needle exchanges and squaring off with Clorox when they didn’t want their brand associated with harm reduction, to community-building with the gurls throughout the southern U.S.

What stands out most to me from Miss Major Speaks is her stories of fighting the state: from fast-paced car chases away from the cops, to direct action and organizing for the gurls (“gurls” is the explicit spelling laid out by Miss Major for references to trans women and femmes in the book), to fighting back against the police in key moments of queer and trans history like the Stonewall riots. Journalist Wren Sanders writes, “Major fought the cops alongside ancestors Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson at the Stonewall Rebellion and supported trans women dealing with prisons and incarceration and issues with lack of access to harm reduction services in the ’70s.”

Not swayed by fame or politics, Miss Major writes about the need to fight for justice in ways that make things materially and physically better for the gurls. She criticizes lots of surface organizing and political promises that have done nothing for trans women, and cautions against this. Miss Major did essential work in the early days of HIV/AIDS, supporting countless folks living with AIDS, and has provided key leadership at organizations, such as the Transgender Gender Variant Intersex Justice Project and House of GG in Arkansas, and is living proof that change-making requires work and collective struggle.

“Cops come, and the white people disappear into the night, and suddenly you’re alone and the only one in cuffs on the ground,” she writes. Quotes like this ground the incredible tome. Miss Major describes cops pushing sex workers for blowjobs in exchange for not charging them, and tells the tale of several near getaways, and of time inside jails and prisons. Unlike Major!, Miss Major Speaks tells a more candid story of her organizing and family life outside of queer liberation. Miss Major speaks openly about her disdain for Pride organizations and marches, as they haven’t helped the gurls in any material or structural way since their inception. She writes that she is tired of telling and retelling stories from Stonewall, for this was but one moment in a revolutionary lifetime of activism and the telling and retelling have been used to fuel queer agendas that have not benefited the gurls.

As an abolitionist, I’m touched by the deep connection Miss Major describes having with Big Black, a prisoner who helped politicize her and introduce her to organizing from inside the jail. I first heard of Big Black from Ceyenne Doroshow, founder of GLITS, a Black trans-lead housing project in New York City, and author of Cooking in Heels, which is about her life as a trans activist. When we met in Winnipeg for the 2014 Decolonizing and Decriminalizing Trans Genres conference, Doroshow talked about her father, Big Black, and his organizing, and introduced her to Miss Major, whom she called “Mama.” In the book, Miss Major brings up Doroshow and remarks on how she began calling her Mama from their first meeting, moved by Big Black’s love for her.

I have been an activist for 26 years and have no plans to stop any time soon. Miss Major’s description of a lifetime in activism and watching people come and go from the movement(s) resonated with me. Miss Major stayed in the fight and has spent a lifetime change-making for all of us. She states at the end of the book, “Why didn’t I stop? Number One is community. My gurls. I’ve had moments of thinking about stopping, but I didn’t. I made sure I would step back, rejuvenate myself, and then got back out there, and that’s how you make a way … you make the best of it all and hope you can help make it a little better for the gurl after you.”

Change-making seems possible and even easy after reading Miss Major’s words. She is committed to transformative and revolutionary processes that will make a world where all the gurls can thrive. As she says in the book, “Europe, Africa, Asia—it’s all the same. Can’t get jobs, can’t get education, can’t get housing, can’t get training. We’re not allowed to do anything but suck dicks, turn tricks and they criminalize all of us. We all have something to offer, if they gave us a chance. If it means that I have to cuss out an auditorium full of motherfuckers one by one just to bring attention to it, I can do that.”

And Miss Major continues to do just that, bringing attention to what we need to focus on and making space for all the gurls.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra