At the beginning of what we now commonly recognize as electronic music, there was a trans woman. Though the pioneering record was published under Wendy Carlos’s birth name, it contained a nod to her identity, hidden in plain sight. There it was, on her 1968 album cover: Trans-Electronic Music Productions, Inc. Presents: Switched-On Bach.

When Kim Petras won a 2023 Grammy for her single “Unholy” with Sam Smith, she gave a moving speech acknowledging the trans artists who paved the way for her historic moment. Petras was the first out trans woman to win a Grammy—but Wendy Carlos was the first, in 1970.

The enthusiastic responses to this tweet (by Xtra’s own Mel Woods!), as well as many popular TikToks and Instagram posts, prove that there’s an enormous curiosity about trans history among younger people.

Carlos, now 83, hasn’t released new music since 1998, and hasn’t done an interview in at least a decade. Many of the most detailed writings on her life and music are old, or careless enough that they still casually quote her long-defunct deadname. A 2020 biography of her was thorough, but received mixed reviews, and was openly denounced by Carlos herself. For complex reasons, including her label shuttering, and her refusal to allow her music to be uploaded to digital platforms—most of her albums aren’t available for digital streaming or purchase at all. However, you can find her TRON soundtrack on Spotify and Apple Music, and this lovingly arranged, career-spanning mix at The Wire magazine.

Carlos’s life doesn’t fit into a neat box, and her experiences as a woman who transitioned in the late 1960s are very different to the trans identity politics of today. But without even intending it, Carlos created an archetype: I myself am one of countless trans women in music and audio production who’s followed in her wake, who was impacted by her life even before I knew I was trans.

For anyone who’s intimately familiar with both, there are clear parallels between musical synthesis and transgender hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Operating a synthesizer involves rewiring signals in electrical circuitry to bring sound into the audible physical realm. HRT involves rewiring the endocrine system to alter one’s mind, body and emotions to their desired state.

In both cases, the organic and technological come together to transcend physical limitations. And simply knowing the technical theory—as a non-musical audio engineer, or a cis doctor—is vastly different to experiencing it in practice.

Would Carlos agree? I can only guess. But the analogy is there, for those open to hearing it. Many subsequent trans musicians, especially SOPHIE, have deliberately adopted Carlos’s approach—synthesis as a form of corporeal transcendence—into their own artistic philosophy.

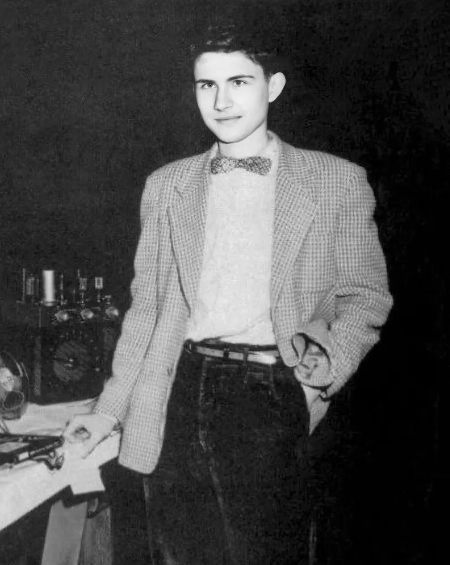

Much of Carlos’s history is relayed through her website, which is still maintained. Born in 1939, Carlos began taking piano lessons at age six, and composed her first classical work, “A Trio for Clarinet, Accordion, and Piano” at 10. By 14, she’d built her own home computer, for which she won a scholarship. As a young adult, Carlos’s dual interest in music and electronics brought her to New York, where she met two people who would change her life forever.

The first was Robert Moog, the inventor of the first commercially available synthesizer, whom she met after graduating from Columbia University with a master’s in music composition in 1964. The two formed a fast partnership, as Carlos recalled in a 1989 interview: “He was the engineer who spoke music, I was the musician who spoke engineering terms. And together, we were able to come up with ideas that I don’t think anyone would have come up with alone.” At her request, Moog implemented touch-sensitive keys into his synths, allowing a similar level of dynamic expression to the pianos upon which they were based.

Credit: The Rafaelite, yearbook of St. Rafael Academy, Pawtucket, Rhode Island

Her second mentor was Harry Benjamin, a pioneer in modern trans medicine, who wrote the 1966 medical textbook The Transsexual Phenomenon, which remains historically significant while now being somewhat outdated and rooted in gatekeeping. Upon coming across the book, Carlos came to understand herself; to give a name and voice to the identity challenges she’d experienced since she was a child: gender dysphoria. She told Playboy magazine in 1979, “Dr. Benjamin’s book was the first to give adequate coverage to the psychical [sic] needs, the emotionality, the personal descriptions of other people who shared my strange condition … It provided an explanation for all the alienated feelings I’d had since my earliest memories.” She became a regular patient of Benjamin’s and started feminizing hormone therapy in 1967.

In 1968, CBS Records launched a marketing campaign called “Bach to Rock.” They had no actual Bach in their catalogue, so they accepted an album proposal from Carlos and her producer-collaborator Rachel Elkind for what would become Trans-Electronic Music Productions Presents: Switched-On Bach, a collection of baroque-era Johann Sebastian Bach pieces played on the synthesizer. As Carlos told Playboy, the concept was revolutionary.

“To my knowledge, there were only three practitioners of the Moog synthesizer when I began. People couldn’t even pronounce the word—synthesizer,” she said.

In the album’s vinyl liner notes, Carlos says she chose Bach’s music because his flurries of notes would be easier to replicate on a primitive synthesizer than slower, more sustained orchestral pieces. Despite involving exceptionally complex circuitry, the early Moog synthesizers were monophonic, meaning they could only play one note at a time, and they were recorded, painstakingly, note by note, in analogue fashion. Each inch of tape contained up to eight manually spliced edits; altogether, the album took over 1,100 hours of work to complete.

Listening to Switched-On Bach, 55 years later, is still dazzling (a vinyl LP rip is available on the Internet Archive, while a 1999 CD remaster also sounds incredible). Bach’s crisp melodic lines and intricate bass-treble counterpoint are compelling in most settings, but using combinations of the Moog’s sine, square, triangle, pulse waves and white noise, Carlos replicates, replaces and expands on the traditional piano, brass, wind ensemble, strings and organ. Those settings, which she came up with essentially from scratch, are still used as fundamental synth patches today, on virtually every piece of music that features a synthesizer.

While the likes of the Beatles and Beach Boys had already used synths in pop songs by 1966, Switched-On Bach was the essential album in the first revolution of the synthesizer. It took the instrument out of the abstract realm of textures and avant-garde compositions, and made it sound harmonic, organic and instantly recognizable as music.

Without even intending it, Carlos created an archetype: I myself am one of countless trans women in music and audio production who’s followed in her wake, who was impacted by her life even before I knew I was trans.

Carlos brought classical music back into the present and the future of popular music. In 1969, Switched-On Bach reached number 10 on the Billboard 200; by 1986, it was the second classical album, and first-ever electronic album to go platinum, selling over a million copies in the U.S. In 1970, it won three Grammys, for Best Classical Album, Best Classical Performance—Instrumental Soloist and Best Engineered Classical Record. It was a genuine phenomenon and spawned leagues of long-forgotten imitation albums. But, on a much deeper level, through Switched-On Bach, the foundation of western classical music and harmony also became the foundation of global popular electronic music.

Subsequent electronic composers were anointed as virtuosos not for the speed or ego with which they played (like Rick Wakeman of Yes, with his many prog-rock keyboards), but the richness with which they operated the synthesizer. From Jean-Michel Jarre to Giorgio Moroder, Depeche Mode to Aphex Twin, The Prodigy to Madonna’s Ray of Light, Britney Spears’s Blackout to Flume, many of the most iconic subsequent works across all genres of electronic music are animated by the same (re)invention of sonic possibilities as Switched-On Bach.

Having already done it once, her approach in her heavily anticipated 1969 follow-up, The Well-Tempered Synthesizer, is already smoother and more sophisticated, this time with more variety in compositions, and stunning use of reverb and stereo mixing.

In the liner notes of The Well-Tempered Synthesizer, Glenn Gould, whose idiosyncratic piano recordings of Bach’s Goldberg Variations a decade earlier made him a classical megastar, declared, “Carlos’s realization of the Fourth Brandenburg Concerto is, to put it bluntly, the finest performance of any of the Brandenburgs—live, canned, or intuited—I’ve ever heard.”

But behind the scenes, Carlos was troubled. She was already living as a woman in her private social life, but with success came attention. The prospect of doing interviews, performing live—really, being perceived at all while having to hide her true identity—filled her with dread. In the Playboy interview, she recalls “crying hysterically” when forced into situations where she had to present as male. Yes, out trans people had existed in public before—most notably Christine Jorgenson, who in 1952 became famous for having transitioned—but the coverage of them was a media circus of fascination, spectacle and invasive gawking. There was no template to follow, no guarantee of safety.

So, Carlos compromised. In public appearances, like the above video for a 1970 BBC program, she did what modern transfemmes now call “boymoding”—dressing to de-emphasize her true gender identity and the obvious effects of HRT. Her wig and clearly fake sideburns add some humour to the situation, but the joke is not on her. In fact, it’s quite extraordinary to see a trans person existing in almost-plain sight, that a sense of her true self shines through despite the lengths to which she went to hide it.

Sadly, she withdrew in private, even dodging calls from the likes of Stevie Wonder (whose 1976 track “Village Ghetto Land” wouldn’t have existed without her influence), George Harrison and Keith Emerson. In a 1985 interview with People (which is particularly egregious in its transphobia by modern standards), she recalled, “I accepted the sentence, but it was bizarre to have life opening up on the one hand and to be locked away on the other.”

At the time, Carlos lived most fully in her work. Her 1972 album Sonic Seasonings is remarkable in the opposite way to Bach: instead of the pointillist notes and scales of baroque music, she began using synthesizers to create longer, evolving textures that were more about evoking atmosphere. Sonic Seasonings arrived at the dawn of what would later be known as ambient music, before that term was codified into a genre. The album contained one composition for each of the seasons, each over 20 minutes long. “Spring” and “Fall” are mostly soothing and pastoral, while “Summer” is all about being buffeted by wind, and “Winter” builds to the howls of wolves—both oddly harrowing pieces.

But through much of the 1970s, Carlos worked in her popular vein. Switched-On Bach II (1973) and By Request (1975) are also both worth the listen, if less impressive than their predecessors. On By Request, she and producer-collaborator Rachel Elkind took suggestions for pieces from the public. Among the usual classical arrangements, the album includes two pop covers: The Beatles’ “Eleanor Rigby,” which feels like pure novelty and one very intentionally silly take on Tom Jones’s “What’s New Pussycat?”

What kept Carlos’s name artistically relevant was her work on film scores. Stanley Kubrick needed someone who spoke the language of classical music for his 1971 adaptation of Anthony Burgess’s novel A Clockwork Orange. But he also needed a composer who understood how to subvert classical beauty with irony; who understood the high and low art of the infamous scene where Malcolm McDowell would be tortured while listening to Beethoven.

The film’s score is a mix of existing orchestral pieces and Carlos’s synth renditions, often retooled with more sinister intent. Through her, the second movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony—redubbed the “Suicide Scherzo”—becomes frantic and hair-raising. “March from a Clockwork Orange” contains one of the earliest recorded uses of the vocoder, which as Carlos recalls on her website, “The first reactions were unanimous: everyone hated it!”

But it was an original piece, inspired by her reading the novel before she and Kubrick even got in contact, that would be the highlight. In its uncut form, “Timesteps” is a 13-minute odyssey where, for the first time, Carlos bridges baroque virtuosity and avant-garde form, until harmony and synthetic textures become practically indistinguishable. Without question, “Timesteps” is Wendy Carlos’s greatest work of the 1970s, and the one track that best summarizes her entire career.

Credit: Digital Transgender Archive

Toward the end of the decade, Carlos came out. She did so with the same level of intent with which she approached everything else—through the aforementioned 1979 interview with Playboy.

“I’ve gotten tired of lying. I think that in the past couple of years, the dangers of allowing the public to know about me have lessened. The climate has changed and the time is ripe. With the appearance of this interview, my friends won’t have to lie and dissemble for me anymore,” she said.

The impacts of her coming-out were twofold; on one hand, she was surprised that her transition seemed of no great consequence to many. In 1985, she recalled to People, “The public turned out to be amazingly tolerant or, if you wish, indifferent. There had never been any need of this charade to have taken place. It had proven a monstrous waste of years of my life.”

On the other hand, Carlos hated the resulting interview. She had been promised by Playboy’s editors that it would primarily be about her music, but the interview is framed as an inquiry into her life story through her medically peculiar sexuality and gender identity. The writer, Arthur Bell, falls into stereotypes, all-around sensationalism and a heavy emphasis on surgeries over other aspects of transition. Carlos grew to resent being objectified, having her narrative reduced to her transness.

However, the level of candour and detail in Carlos’s responses make the piece an incredibly powerful memoir, and essential reading for anyone interested in historical conceptions of transness. Her anecdotes and descriptions of envy, dysphoria and depersonalization will be instantly familiar to many trans readers. In the end, as long as trans people can speak for ourselves—no matter how misguided the framing might be—we can find glimpses of recognition, even solidarity, in our own narratives.

Switched-On Brandenburgs in 1979 was her first release to be issued under the name Wendy Carlos, as all her future albums and reissues would be. On it, she completed a cycle she’d begun on her debut, recording Bach’s remaining three Brandenburg concertos. Compiled together, the six suites are as dazzling and virtuosic as ever and also a logical endpoint for that style of music. At decade’s end, it was time to move on.

Stanley Kubrick rehired Carlos for 1980’s The Shining, for which she composed and recorded at least an hour of original synths and orchestrations. However, and to her great disappointment, Kubrick discarded the majority of her material, not unlike the liberties he took with adapting the Stephen King novel. Ultimately, though, she admired Kubrick for being a similar kind of control freak to her—albeit a much more temperamental one.

In the end, history proved him right to do so. Carlos’s original score, released on Rediscovering Lost Scores—Volumes One & Two (2005), is excellent unto itself, but would have added an emotional grounding, even warmth, to the film. Instead, Kubrick created a brutalist space, using Carlos’s two all-time most terrifying recordings—her blaring title theme, aka “Dies Irae,” and the unnerving “Rocky Mountains,” which, alongside other works by modern classical composers György Ligeti, Béla Bartók and Krzysztof Penderecki, hinted at cosmic, unspeakable horrors—and proved that Carlos belonged in their pantheon.

Her 1982 score for Disney’s TRON took her from horror to children’s sci-fi. A mix of live orchestra and synthesizers, some tracks, especially the main theme, perfectly nail the film’s sense of childlike wonder and technological singularity. But overall, the music doesn’t play to her fullest strengths—Carlos never aspired to, say, John Williams’s knack for sentimentality, nor mixing hooky melodies with grand orchestration.

For rights reasons, The Shining and TRON remain her only works on streaming services. Neither are fully representative of her work, though her theme for The Shining has now become her most recognizable piece of music.

By the early 1980s, the second revolution of synthesizers was well underway. Those giant analog Moogs gave way to digital synths: the likes of the still-complex Fairlight CMI, and then the Yamaha DX7, which was small enough to be accessible to home consumers. Fully synthetic pop songs were becoming commonplace: Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love,” Gary Numan’s “Cars,” Depeche Mode’s “Just Can’t Get Enough.” The Switched-On Bach revolution had fully arrived in popular music.

For Carlos, the digital synthesizer was the instrument she’d always dreamed of—yet she’d seemingly discarded any interest in pop music and its adoption of the synthesizer.

She explained her distaste for disco’s repetitive grooves to Playboy, saying, “This may sound like sour grapes, but I’m putting down almost all of the records that have used the synthesizer this decade … I don’t want to stop them. I’m only saddened to see that [the music] isn’t further advanced.”

Her first fully digital album, 1984’s Digital Moonscapes, is really her only release that, in this writer’s opinion, can nowadays be considered mediocre. It’s neither atmospheric enough to work as an ambient record, nor intricately composed enough to be a compelling modern classical work. The compositions lack a strong direction, and overall feel more like a tech demo, but not in the groundbreaking way that Switched-On Bach had been.

But two years later, Carlos blew the doors wide open again. Beauty in the Beast (1986) is a fully microtonal album, meaning Carlos turned away from western music’s traditional, symmetrical 12-note octave, instead using scales based on odd mathematical ratios that could ignore octaves altogether. In summary: it sounds really fucking trippy.

Microtonal music can be unsettling if you’ve only ever heard instruments in traditional tunings, but the way in which it rearranges your brain is completely unique. This was music that would have been nigh impossible to create with analogue synths; whose intervals sound unreal, shimmery, like your ears have been inverted and turned inside-out. “Incantation” is worthy of Antonín Dvořák’s New World Symphony; the title track blasts into a topsy-turvy circus fanfare; while “Poem for Bali” incorporates Indonesian-inspired gamelan and flute synth patches.

On her website, Carlos called it “my most important album … my fondness for Beauty is deeper and more personal” than for Switched-On Bach. It’s tempting to call the album her masterpiece, but it’s open-ended and exploratory, rather than definitive. For all her innovations, Beauty in the Beast is her one work that’s still decades ahead of its time; that still has enough familiarity to be the perfect introduction to the possibilities of microtonal music. She saw alternative tunings as the future, and in a way, they still are—so much of their potential is still untapped.

Her subsequent work is easily overlooked, but the gems are still there. Peter & the Wolf (1987) was a children’s novelty record with none other than “Weird Al” Yankovic, an artist who grew up a fan of hers.

The same year, Carlos explained her approach to sound design on Secrets of Synthesis (1987), which still functions as a better introduction to synths than the majority of modern online audio courses.

Her two albums released in the 1990s looked to the past and the future. Switched-On Bach 2000 (1992) was not a re-creation, but a restaging of the original. Using digital technology that was then a figment of her imagination, she made new orchestration choices in the moment. Though 2000 lacks the spark of an artist inventing in real-time, Carlos’s mastery is still apparent, especially on the new addition “Toccata & Fugue in D Minor.”

Tales of Heaven & Hell (1998), though, is the strangest Wendy Carlos record, after Beauty in the Beast, using choirs and her full range of synth patches to often atonal, nightmarish effect. The album cover even features a disclaimer: “Contains genuinely scary material. Use caution when listening alone or in the dark.” Much of the material feels more like intriguing sketches than fully developed compositions, leaving more unsettling questions than answers.

But its final track, “Seraphim,” is the most gorgeous piece of her career. It feels like her looking back on the ups and downs, struggles and beauty of a life lived. Tales is her final recorded album to date, and, assuming it stays that way, “Seraphim” is a hell of a way to go out.

With one of her most ambitious works done, Carlos and her record company embarked on an elaborate campaign of remastering all her works for CD. In the liner notes of those reissues, and on her newfangled website, she reflected on her life’s work.

On “Hybrid Timbres” from Secrets of Synthesis, she confesses, “I used to hate being a composer in the late 20th century. With so few possibilities considered acceptable by much of the music world, it felt like we were all trapped in a little cul-de-sac. But now I barely sleep nights, with all the excitement of possibilities becoming real with at least a few computer synthesizers … What a great time to be a composer!”

As the new millennium dawned, the third revolution of synthesizers was just beginning. Software-based synths and plugins like Massive and Omnisphere, utilized in digital audio workstations like Pro Tools (Carlos herself used the relatively obscure Digital Performer), would make synthesis even easier, and the potential for more complex sounds even greater. She had predicted this shift in the above 1989 BBC interview:

“We can now have a democratization as has never occurred before … Very few children might learn to play piano, but an awful lot of us are now going to be able to learn with our computers, and with our keyboards, how to play music.”

Ironically, as electronic music production has become more accessible, Carlos’s music has become more obscure with each generation. Her only released works in the 2000s are the two volumes of Rediscovering Lost Scores, compiling unused pieces from The Shining, TRON and other films. Due to distribution issues from her now long-defunct record label, her other albums haven’t been reissued on vinyl since the 1980s, or CD since the early 2000s. Her music has never been available to purchase on any digital format, and almost none of it is on streaming services, including YouTube, where any unauthorized uploads get hit with takedown notices from her legal company, Serendip LLC.

Because Carlos hasn’t publicly commented on her music’s availability in over a decade, it’s hard to know if she’s stubborn and holding out, doesn’t pay attention or doesn’t care about the ways in which her music has been left behind.

In the 2020s, Carlos’s legacy has become complicated. In a broad sense, every electronic musician of the modern era has been impacted by Wendy Carlos’s innovations in the process of synthesis. However, those innovations have become so totally subsumed that they’re now a default part of the instrument itself.

Many electronic musicians make music that sounds and feels nothing like her formative works. In the early 2000s, cutting-edge electronic music got glitchier, more abstract— Aphex Twin’s increasing experimentation; Radiohead’s Kid A setting a new standard for how we heard art music. Next to such anxious postmodern works, Switched-On Bach seems quaint: an optimistic vision of the future that now sounded like the past. Those same kinds of artists, who owe Carlos some lineage through works like A Clockwork Orange, Sonic Seasonings and Beauty in the Beast, may not even have heard her music.

In popular electronic music, dance producers consider their godfather to be Giorgio Moroder, not Wendy Carlos. And when Daft Punk did their score for the 2010 film sequel TRON: Legacy, they were inspired by Carlos in spirit—but created a much more straightforward, nostalgic work, with none of her score’s harmonic complexity or tension.

Carlos has been canonized by music journalists, but primarily as a great film score composer and technician—not to the depth or extent to which she deserves. In 2004, The New Rolling Stone Album Guide gave her a backhanded compliment: “Much less satisfying than that of such avant-gardists as Terry Riley, her work flashed more technique than imagination.” Veteran reviewer Piero Scaruffi sums her up reductively: “If most of her records are worth little artistically, and seem more and more like archaeological curiosities, Wendy Carlos remains one of the most important precursors of the electronic age.”

It’s true that Carlos wasn’t as consistently radical as her modern classical peers like John Cage, Philip Glass or Steve Reich; never as prolific or interested in pop collaboration as the other ambient pioneer Brian Eno; much harder to pigeonhole, and therefore less instantly recognizable, than other early electronic film composers Vangelis and John Carpenter. But Carlos was equally adept at breathing new life into traditional classical harmony, subverting it with dissonance, and pioneering new technologies—a truly singular combination of talents.

Ironically, as electronic music production has become more accessible, Carlos’s music has become more obscure with each generation.

Notably, all of those names are men. Carlos’s direct female peers, like Delia Derbyshire, Pauline Oliveros, Suzanne Ciani and Laurie Spiegel, were not as prominent as her in their time, never granted the oft-masculinized label of “genius,” and are slowly being re-evaluated as auteurs only now.

Carlos never wanted to be heard or reduced to solely being a female or trans composer. Since she came out, her music has rightfully been perceived and understood as having been made by a woman, but it’s impossible to fully quantify how Wendy’s womanhood and transness affect that perception. And until recently, she has largely been written about by men, with little sympathy for the specifics of her gender.

All of this has meant that in headlines and sound bites, Carlos has been reduced to two symbols: Switched-On Bach and her transition. No, not the music of Bach, but the memory of the painstaking process and the innovation, removed from the sound itself. And by cisgender journalists, she’s rarely situated within broader trans history—simply noted for her unusual medical transition and name change.

In 2020, the Washington Post titled a review of her biography thus: “Wendy Carlos, the electronic music pioneer who happens to be transgender.” While well-intentioned, and close to Carlos’s own preference for how she prefers to be depicted, such angles completely overlook the intersection of her identities.

Both Switched-On Bach and her transition are important as symbols, but they lose meaning when decontextualized. They become glorified trivia answers, rather than artwork and history to be engaged with on their own terms; living things that can continue to inspire new thought.

To fully appreciate Carlos’s impact, you have to understand her significance as a kind of godmother figure to trans women in particular. She was one of the first trans people to be famous for something other than being trans.

On The Things That Made Me Queer podcast earlier in 2023, Natalie Wynn—aka the YouTube video essayist and “ex-philosopher” ContraPoints—spoke about hearing Switched-On Bach for the first time.

“I was a music nerd in high school. I was in the orchestra, I played piano, and so this was interesting to me. And then I learned that she was a trans woman,” Wynn recalled. “Wendy Carlos is not a person who likes a lot of public attention. She’s never really made a big deal of it, and has been private. But just knowing that there’s a person who’s a trans woman, who’s doing things in the world, is accomplished and is achieving something cool—I feel that kind of planted a seed that made me think that you could be a trans woman and be more than what trans women are usually [depicted as].”

Carlos’s legacies most intertwine in the new generation of trans women who make electronic and and experimental music: the late synth genius SOPHIE, game composer Lena Raine, hypnotic jazz auteur Time Wharp, vaporwave pioneer Vektroid/Macintosh Plus, Venezuelan deconstructed club producer Arca, gut-wrenching noise artist Uboa, trans-voice and microtonal witch Zheanna Erose, and the radical microtonal metal experimentalists Liturgy and Victory Over the Sun. All of them make music that’s technically masterful, but more than that—is heady, emotive, indefinable and irreducible.

Much of their work evokes a sense of transness and dysphoria, explicitly or as subtext, in a way that’s far clearer than that of Wendy Carlos’s music and identity. But there’s a similar kind of transcendent unreality in Beauty in the Beast and a song like SOPHIE’s “Whole New World/Pretend World.” They both exist in the space where transness and technology meet; where science fiction becomes a possibility.

We can’t fully separate art from life, nor the process or politics of its creation. For me, denying the transness inherent to my point of view was suffocating. I never fully understood my relationship to creativity or identity until I accepted myself as a trans woman, started HRT, and realized that I had always been a writer and artist in the lineage of other queer trans women. By embracing trans identity and community, our work can never be reduced to a token symbol of what transness means to cis people

That objectification was Wendy Carlos’s greatest fear. Her own opinions are more complex than I can fully summarize; but for someone of her generation, it’s understandable that transness and gender dysphoria were simply a genetic hurdle to overcome. But many of us now look to transness and transition as a blessing and as liberation not just from our physical limitations, but binaries altogether. We look up to Wendy Carlos because we see our own possibilities in her.

In an Instagram post responding to the Grammys, Arca wrote, “You don’t know about her by choice—she does no press, has no official biography or autobiography, and seemingly gradually lost interest in being known for her talents. Like Sade, Enya, Kate Bush and countless other musicians I love she bowed out from the spotlight, ostensibly to live a normal and fulfilling life away from the noise of a spotlight that praised her and alienated her all at once. We love you Wendy, and you’re still alive, still with us! I hope the message reaches you that your oeuvre has meaning to us.”

There is clearly an enormous, yet unsatiated interest in Carlos’s work and life. Unfortunately, audiences may not get easy legal access to her music while she’s alive.

However, it is a misconception that we need streaming services to determine what is available to us. Those giant, fickle, ahistorical media conglomerates have proved time and time again that they do not have artists’ best interests at heart. You can and should find Wendy Carlos’s music; it is the most important aspect of her life. Though she’s often characterized as a recluse, she’s not a mystery. She speaks for herself through her art, and through her incredibly detailed personal website.

Beyond that, if we’re not willing to seek beyond what Google, social media or streaming services serve up to us—how are we ever going to preserve musical or trans history? So much vital analogue and early internet music criticism has been lost to time; trans history is even more fragile. To limit our range of experiences is to limit our individual thoughts and collective memories alike.

The need to not just preserve, but to continue Carlos’s artistic, cultural and personal legacy is essential. The deepest writing on her, which encompasses the full dimensionality of her life, is largely by other trans people. A 2019 piece in Playboy even addressed the failings of the magazine’s 1979 interview with her: “It was, after all, one of the few pieces of original journalism about trans people in the mainstream media in the late 1970s. Yet a re-reading reveals troubling ways in which gatekeepers, ostensibly charged with faithfully presenting our emergent stories, failed.”

We need to give Wendy Carlos the flowers she deserves while she’s still alive, so that every trans person may grow old, happy and fulfilled as she has. Trans people need to be the custodians of our own history, so that we can be the architects of our present and future.

I listened to all 17 and a half hours of Wendy Carlos’s officially released music for this profile; all of it is deeply human. The scope I get from her work is a life of infinite curiosity: anything of her imagination could be realized within the four walls of her home studio.

We need to give Wendy Carlos the flowers she deserves while she’s still alive, so that every trans person may grow old, happy and fulfilled as she has. Trans people need to be the custodians of our own history, so that we can be the architects of our present and future.

When Playboy asked her what would’ve happened if she hadn’t pursued medical transition, she replied, “I would be dead … Sure, it was necessary for me. But I don’t think it’s been positive at all. I feel that what I achieved is the removal of one very large negative in my life. Now that I’ve solved my gender crisis, I’ve still got to come to grips with the other parts of life that go into making a happy individual: living a productive existence; having time for other human beings; having time for passion and compassion; having the time to create and shape the multifaceted diamond that a fine life can be.”

The trans experience all too often brings us close to the precipice, but most of us today would say that transition is about far more than alleviating dysphoria. It’s about reclaiming the possibility of joy in our lives, discarding the structures that don’t serve us and the limitlessness of human potential.

Wendy Carlos’s music is never basic—it’s foundational. More than 50 years later, Switched-On Bach is still the best place to start learning about synthesis. The process is easier than ever, but there are no shortcuts to great artistry.

To listen to her is to hear the magic in electronic music; the inspiration in every note; to fall in love with the infinite possibilities of sound all over again.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra