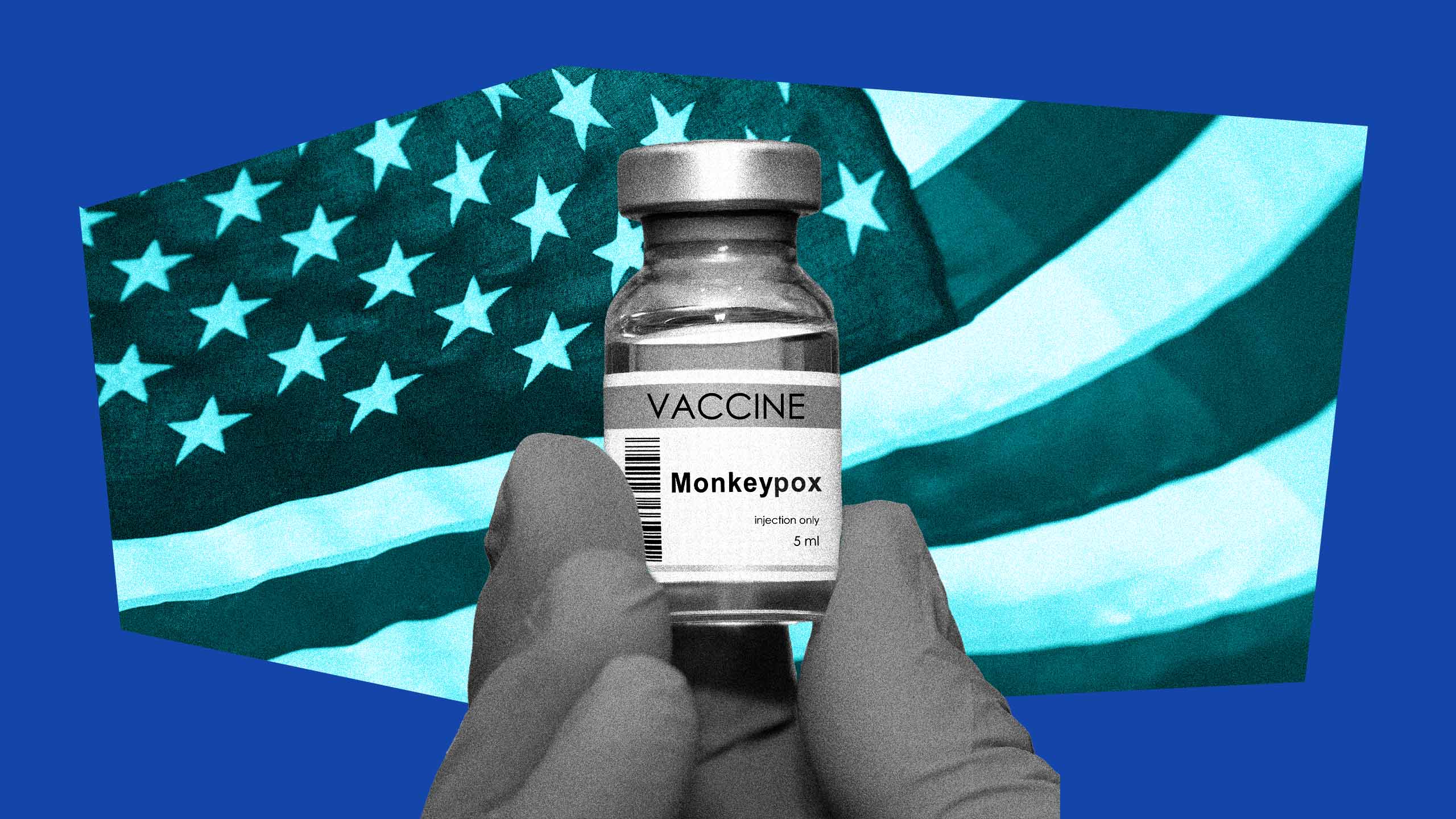

As of Jan. 31, the U.S.’s public health emergency declaration for mpox is officially over.

A Dec. 2 statement from Department of Health and Human Services secretary Xavier Becerra said the emergency declaration, which had been extended once in November, would not be renewed again after its Jan. 31 expiry date.

“Given the low number of cases today, HHS does not expect that it needs to renew the emergency declaration,” the statement reads. “But we won’t take our foot off the gas—we will continue to monitor the case trends closely and encourage all at-risk

individuals to get a free vaccine.”

Mpox, formerly known as monkeypox, is endemic to Central and Western Africa. It first started noticeably spreading North America, Europe and Australia last May, prompting the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare a public health emergency in July. The U.S.’s emergency declaration followed in August.

At its peak in early August, an average of 450 mpox cases were being diagnosed every day in the U.S., and people were queuing up to receive vaccines that were fast-tracked through the approval process. To date, around 30,000 cases have been recorded in the country, along with 28 deaths.

But the spread declined through the fall and winter, and the number of mpox cases in the U.S. fell dramatically. Vaccines, changed behaviour and colder weather may all have played a part.

After a bumpy initial rollout, wealthy countries managed to organize a large-scale vaccine rollout, with queer men and trans people being eligible for vaccines.

By the beginning of November, more than a million doses of mpox vaccine had been administered in the U.S., along with more than 100,000 in Canada. But vaccines in wealthy countries alone did not completely curb the spread; one study suggested the vaccine may have been less effective than initially hoped, while only around 36 percent of the roughly 2 million eligible individuals in the U.S. had been inoculated with the first dose.

Studies published last fall also suggested few cases spread through saliva or surface contact, making mpox less generally transmissible than initially feared.

Alongside vaccines, almost half of queer men in the U.S. reported decreasing their sexual activity as a response to the virus. Awareness of the virus was widespread.

“We can really credit community action for the success we’ve seen, be it with vaccine uptake or the messaging and education around [mpox] symptoms and self-care,” Dr. Troy Grennan, an infectious diseases physician and HIV/STI lead at the BC Centre for Disease Control, told Xtra last year.

“There were concerns that there would be ongoing transmission and that ongoing transmission would become endemic in the United States like other STIs: gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis,” Dr. Jonathan Mermin, director of the CDC’s National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD and TB Prevention, told CNN. “We have not seen that occur.”

Men who had sex with men were disproportionately affected by the outbreak, which scientists believe first started spreading in the West at two raves in Belgium and Spain, and largely spread through sex.

“In this outbreak, in this time and context to Europe, United States and Australia, [mpox] was definitely sexually transmitted,” Dr. Jeffrey Klausner, a clinical professor of public health at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine, told CNN.

He said that the Center for Disease Control (CDC) likely downplayed the sexually transmitted messaging due to concerns around the “stigma of the type of sex.

“It was actually a political calculation to garner the resources necessary to have a substantial response to be vague about how it spread,” he added.

However, people who caught mpox reported feeling like outcasts due to the stigma around the disease, especially when its contagiousness was unclear. Mpox also disproportionately affected communities of colour, particularly Black and Latino people, likely due to compounding forms of intersecting marginalization, like healthcare barriers or medical racism. In its early weeks, a lot of misinformation spread about the virus.

Although the U.S. is dropping the emergency declaration, mpox is by no means gone. Worldwide, less wealthy countries did not have equitable access to vaccines, and parts of Africa and Southeast Asia still have raised levels of the virus. Even in North America, the current cold weather means there are fewer large-scale social events; case counts could climb again when the weather gets warmer and parties return.

Mermin said that continuing to roll out vaccines, especially to vulnerable populations like those with HIV, would be key in trying to keep case counts low.

“So much of our work in the next few months will be setting up structures so that getting vaccinated is easy,” he said.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra