It’s been two years since Judge Gregory Moore of Quebec’s Superior Court of Justice ruled that the province’s laws needed to be updated to recognize non-binary identities. And it’s been nearly a year since Quebec passed the major legal update to its family law which allowed non-binary people to identify their gender with an X marker on official documents, or register as a newborn child’s “parent,” rather than having to choose “mother” or “father.”

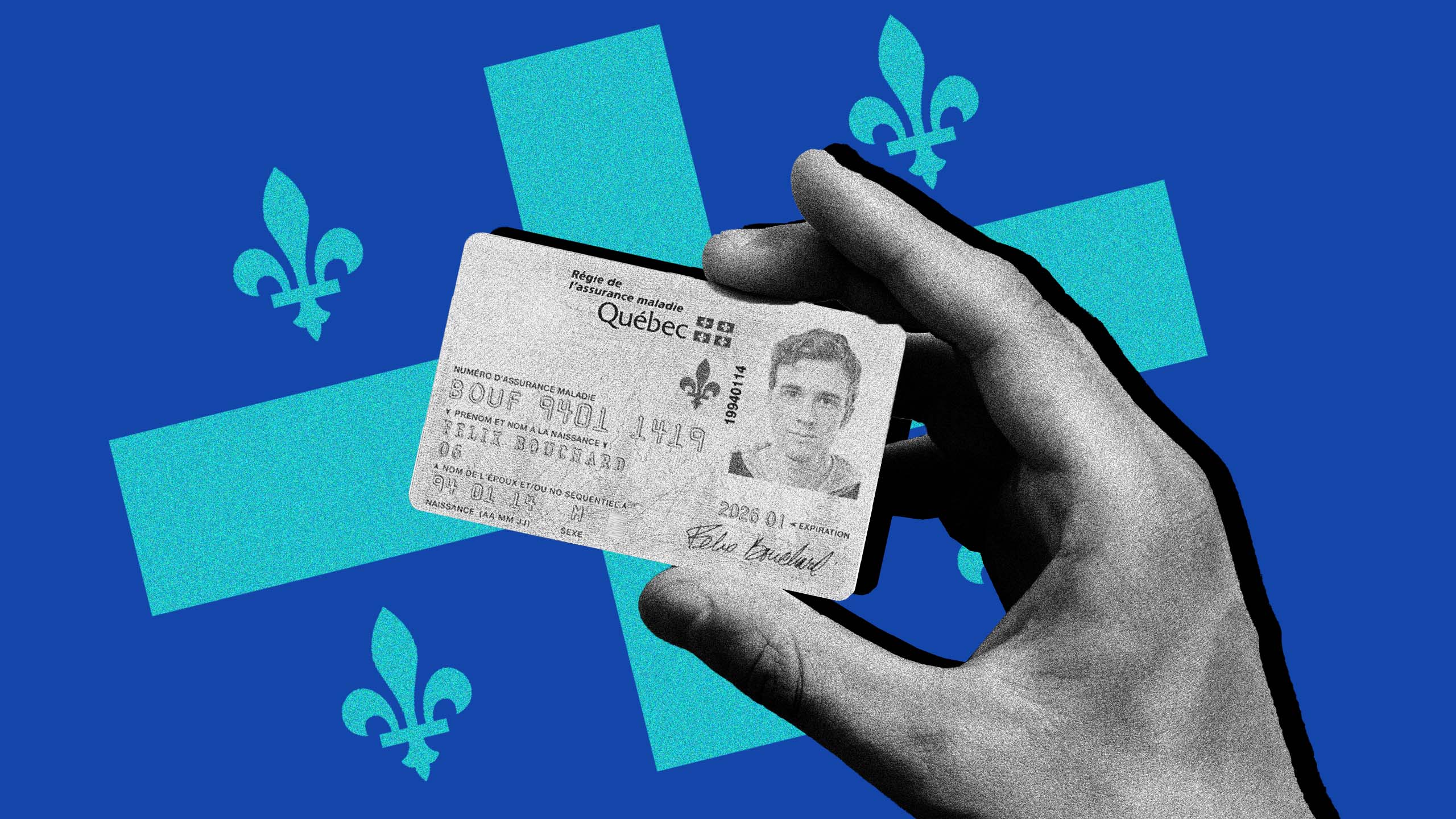

But despite this progress, trans and non-binary residents of the province say that they’ve had trouble getting gender-neutral health cards.

“I was just floored at how slowly everything was moving because we’ve known since January 2021 that the X sex marker was coming to the papers in Quebec. So it’s been two years now,” Montreal resident Alexe Frédéric Migneault told CTV News.

The Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec (RAMQ), the provincial health insurance board, said that currently they can only issue health cards with an M or F on it, ignoring both X markers and the possibility of no sex marker at all.

“That feels incredibly disrespectful and incredibly, just, dismissive of them,” Migneault said. “I wish that they took the responsibility toward the whole Quebec population, not just binary people, and gave us the answers that we need.”

Having an accurate gender marker on health cards ensures that non-binary people are identified correctly when interacting with medical staff. Bureaucratically, having the same gender marker across all pieces of ID helps prevent confusion or misgendering. And having accurate ID has been shown to improve trans people’s mental health.

The Quebec government has had a rocky relationship with trans people in recent years. During the updates to family law, the government originally proposed legislation that would have made trans people who do not have bottom surgery only able to update “gender identity” on their birth certificates, rather than “sex,” which would have functionally outed them as trans. It was changed after being widely decried as transphobic.

Although non-binary identities are recognized federally on Canadian passports, most documents—including healthcare cards, driver’s licences and birth certificates—are issued by provincial bodies. Different provinces have enforced legislation at different times to grant basic identity rights to non-binary people.

Non-binary people in B.C. have been able to get an X marker on their health services card since 2018, for instance, while health cards in Ontario do not list sex at all. This means a trans person in Ontario who does not change their name would not need to go through a bureaucratic process to update their health card, though they still would for updating their driver’s licence or photo ID. (Non-binary Ontarians have been able to get X markers on most documents since 2017, and on birth certificates since 2018.)

Manitoba faced similar criticism last year for not issuing updated care cards to trans people, or not updating the relevant electronic health records when cards were updated. At the time, a spokesperson for the provincial government told CBC News that “complex” applications experienced longer delays in receiving updated health cards.

Nunavut currently has legislation to allow people born in the territory to change their birth certificate, but it is unclear how trans people can change gender markers on other documentation. There does not appear to be an option for X markers on Nunavut-issued documents.

According to an access to information request filed by Montreal-based trans activist Celeste Trianon, 151 people in Quebec applied for an X marker between May and September last year.

“It’s, frankly, ridiculous how long the Quebec government is taking,” she said to CTV News, adding that provincial constitutional challenges pushing for non-binary advocacy first started in 2014.

According to the 2021 federal census, there are 16,225 trans and non-binary people living in Quebec, the third-highest total number of people in any province. However, Quebec has the lowest proportion of trans people or any province, at only 0.23 percent.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra