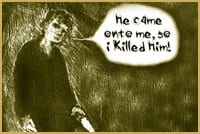

There is no excuse for the fact that people who kill queers in Canada can still get lighter sentences if they say they lost control because their victim came onto them, says lawyer barbara findlay.

Findlay is referring to what’s commonly known as the homosexual panic defence, which killers have successfully used for decades to argue that they shouldn’t be held entirely responsible for their actions because they were provoked by the victim’s homosexual advances.

It’s a common scenario in Canadian courtrooms, says researcher Douglas Janoff.

The scenario goes something like this: Bob meets Frank at a gay bar. They decide to go back to Bob’s place, where they start having sex. Frank freaks out, grabs a knife and stabs Bob 60 times. Then Frank tells the court he panicked because Bob came onto him. Frank gets convicted of manslaughter and serves less than seven years in jail.

In Canada, the homosexual panic defence falls under the category of provocation defences used to knock murder convictions, which carry mandatory life sentences, down to manslaughter, which carries no minimum sentence. The Criminal Code defines a provocation as: “A wrongful act or insult that is of such a nature as to be sufficient to deprive an ordinary person of the power of self-control.”

The question is: should a homosexual advance really be construed as a “wrongful act or insult” so serious as to “deprive an ordinary person of the power of self-control”?

No, says lawyer Garth Barriere. “I think the homosexual panic defence is an improper use of the provocation defence. Why do we allow people to be deemed to have lost control in these situations? Is it so abhorrent to have your sense of sexuality challenged?”

The homo panic defence is based on the assumption that a gay man’s advance “is such an affront to the ordinary straight-identified man” that it’s understandable that they’d lose control and kill, Barriere says.

“It feels like we’re about 50 years behind the times,” says Janoff. “It sounds like honour killing, like this man denigrated my masculinity and I had no choice but to kill him. I see it as another form of systemic gaybashing.

“It’s not acceptable in our day and age for someone to be able to kill me and get a reduced sentence just because I touched their bum,” the author of Pink Blood continues.

A hundred years ago, if a man called another man’s wife a slut, he could turn around and kill him and successfully claim he was provoked, Janoff notes. Provocation is socially constructed; it’s a reflection of what our society considers reasonable today.

“If a gay man says ‘you look hot’ or comes onto you — in our day and age is that considered sufficient provocation?” Janoff asks.

What about if a straight man comes onto a woman and she turns around and kills him and claims she was provoked? Would the courts accept that as a legitimate provocation, he asks. Probably not, he replies.

But when a straight man claims he was the victim of a homosexual advance “somehow that resonates and finds sympathy in our system — and it has to stop,” he says.

Janoff says his research, spanning cases from 1990 to 2003, revealed that across Canada another man claims he was provoked and pleads guilty to manslaughter every four to five months.

One of the most notorious cases in Vancouver occurred in 1994, when Gary Gilroy went home with David Gaspard and stabbed him 65 times with at least five different knives, butchering his body beyond recognition. The Crown could not disprove Gilroy’s theory that he was provoked into a killing rage by an unwanted sexual advance. Gilroy pleaded guilty to manslaughter and was sentenced to five years in prison.

More recently, BC Supreme Court Justice Patrick Dohm invoked similar language in July while sentencing Jatin Patel to nine years for the manslaughter of Shelby Tracy Tom, a transsexual sex worker.

Patel admitted that he got angry when he discovered Tom was transsexual, so he lunged at her throat and killed her. “The accused acted on an impulse and became obviously angry to the point where he could not bring it under control and struck out at Miss Tom,” Dohm ruled.

“This is happening way too often and people aren’t questioning it,” says Janoff.

Liberal MP Hedy Fry has been promising to look into the homosexual panic defence for at least five years. She has yet to introduce a motion in Parliament.

“We have looked into it a great deal,” she says, when asked what progress she has made. Former Justice Minister Martin Cauchon was interested in addressing it, she notes, but then everyone got caught up in the same-sex marriage debate. So the homosexual panic question “has just been sitting in a corner.”

“It would be something to bring up again,” Fry says.

“I do think that it has been abused,” she continues. “Provocation as a defence can be and has been used to get people off in instances that many of us did not think was valid.”

Still, she says, the provocation defence has legitimate uses and “tampering with it would do more harm than good.”

If the government passes a directive ordering courts to remove homosexual advances from the list of possible provocations, it could “open the door to everything becoming an exception,” she warns.

“You can’t just take out homosexuality,” Fry says. Then other groups, such as Muslims, will say they want allegedly race-related forms of panic removed from the list of provocations, too. They’ll say “you shouldn’t be allowed to panic if a Muslim approached you on the street after 9/11.”

Findlay isn’t buying it. Though she says there is much debate over whether the provocation defence itself is worth preserving, there should be little debate over removing homosexual advances from the list of acceptable provocations.

“Whatever you do with the rest of the provocation defence, make it clear that it doesn’t apply to homo panic,” she says.

All the government would have to do is pass legislation saying: “Notwithstanding anything else in this section, the defence of homo panic is hereby rescinded as a valid provocation defence.”

“There is no justification for continuing to include the homosexual panic defence,” findlay continues. “We can amend this part and get rid of the dreadful homosexual panic defence and let them ruminate about the other parts of the provocation defence for as many decades as they think it might require.”

Former NDP MP Svend Robinson agrees. He introduced a private member’s bill in February 2002 asking the government to exclude homo panic from the provocation defence. The bill never got past first reading, but Robinson says he’ll try again if reelected.

“If we’re going to have a [provocation] defence, it should be limited to those situations where people do actually lose control,” Barriere says.

The government could hold off issuing a directive and wait for the judicial system to evolve on its own, he notes. Already, in some cases, judges in Canada and the US have rejected homosexual advances as legitimate forms of provocation. But it could take awhile, Barriere says. “I’m not saying we should wait.”

Janoff doesn’t want to wait.

“It’s obviously a legal issue that needs to be debated by legal scholars,” he says. “But the problem is, the legal scholars have been debating it for 25 years and I haven’t seen any change.

“It would be fine if it had fallen out of use — if it were a relic from the past. But the thing is, this is being used.”

The answer, Janoff concludes, “is to develop guidelines that will prevent this defence from being used to cloak cases of homophobic violence.

“So that we can be assured that institutionalized homophobia has no place in our legal system.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra