“The femme comes first for a reason,” says Marie Robertson with a sly twinkle in her eye as she explains the title of her favourite book, The Persistent Desire: A Femme-Butch Reader.

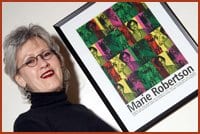

The comment reveals Robertson’s playful disposition, but also points to an underlying drive to shake up the entrenched order of things. For more than 30 years, she’s been the leading femme in the fight for queer liberation and advancement in the province, including co-founding the Coalition For Lesbian And Gay Rights In Ontario (CLGRO). She’s also been a leading AIDS activist. Now, after a long absence in Toronto, she’s helping energize Ottawa’s queer community once again.

Robertson first lived in Ottawa from 1975 to 1984. She came back in July, 2004 with partner Lucy Chapman. One of the motivations for the move was their hope to adopt. According to Robertson, the Children’s Aid Society Of Ottawa is the most queer-friendly adoption agency in the province. Since last summer, she and Chapman have been proud parents of six-year-old Ana.

The demands of motherhood certainly haven’t dampened Robertson’s volunteer spirit. She’s on the steering committee for Ottawa’s queer community centre project, works with three other women to run the Lesbian Information Xchange and does volunteer palliative care work four hours a week each at the Elisabeth Bruyere Health Centre and the May Court Hospice. And that’s all in addition to being a self-employed counsellor, educator and workshop leader, helping raise her daughter, caring for four cats and a Labrador retriever, and hitting the ballroom floor with the Let’s Dance queer group for a little rhumba, tango or cha-cha now and again.

If Robertson’s life sounds like a veritable whirlwind, you wouldn’t know it from her calm composure. Her home is warm and inviting, and she speaks with quiet confidence. Still, a seething underlying intensity bubbles over from time to time, particularly when discussing her 36 years on the frontlines of queer activism in Ontario.

“I have never not been an activist,” says Robertson. “When I came out, we didn’t have basic human rights in this province. We were deviants in the eyes of the medical and psychiatric professions, sinners in the eyes of the church and criminals in the eyes of the law.”

An exchange with a Kitchener landlord in 1974 became a defining moment for Robertson. She and some friends were looking to rent a house together. When the suspicious landlord asked her if she was a lesbian, Robertson, who says she has been “out and screaming” since she first realized her sexual orientation, said yes. The landlord took it as an opportunity to exploit them.

“He said he would still rent to us,” she says with disgust. “Then he said, ‘Queer people have to learn that they should pay more for things than normal people do.'”

Robertson and her friends decided to fight back and complained to the Ontario Human Rights Commission. Because lesbians had no protection under provincial legislation at the time, they lost that battle. But the war was just getting started. In 1975, Robertson helped found CLGRO, a group that was instrumental in achieving the addition of the term “sexual orientation” to the Ontario Human Rights Code in 1986.

Robertson’s peers recognized her long-time commitment to our causes in 1994 when they awarded her the Canadian Lambda Award For Excellence In Human Rights. She calls it one of her proudest moments. But 1994 was also the height of the HIV-AIDS crisis in North America, and her palliative care work with AIDS patients had a profound effect on her personal and professional life.

“The time of AIDS was a high time and low time,” explains Robertson. “I saw us rally as a community in a way that was magnificent. We changed the face of the medical profession and changed palliative care. There was lots of activism, but profound sadness too. When I left the AIDS Committee Of Toronto, I was up to 300 deaths.”

Adversity has touched Robertson repeatedly. She survived a brush with cervical cancer in her late 20s, and lost many close friends and fellow activists to AIDS. But quitting has never been an option, and she continues to work to advance queer rights with the same fervour she always has. Asked what keeps her motivated, Robertson doesn’t miss a beat.

“I don’t take for granted for a minute that the rights we have fought so hard for cannot be lost in the blink of an eye,” she says. “The younger kids, because of our hard work in the past, they don’t feel the same need for a sub-culture. It’s great that they can benefit from our work, but the rights they have today could be taken away. We cannot rest on our laurels.”

These days, Robertson has committed herself to moving the community centre project forward. She believes it’s a key to continued development of the queer community in Ottawa.

“I found it challenging when I came [back] to Ottawa,” she laments. “The community in Ottawa is not very visible. In Toronto, when I needed a hit, I’d go to Church Street to feel like I’m safe, to feel the energy. I’ve seen what a community centre can do in Toronto with the 519. We need a space here.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra