After a years-long legal battle, one New York activist has secured crucial reforms for unhoused trans and disabled people in the city. Mariah Lopez’s settlement will create multiple dedicated shelter spaces for unhoused trans and gender nonconforming people, and assure protections for disabled trans people.

“For TGNC [trans and gender nonconforming] individuals and those living with disabilities, navigating the homeless shelter system can be a matter of life or death,” Lopez tells Xtra. “Everyone deserves safe, dignified housing options.”

Under the terms of the settlement, the city of New York will be required to establish shelters dedicated to serving trans and gender nonconforming people in Brooklyn, Manhattan, the Bronx and Queens by the end of 2022. The units must also include accommodations for disabilities, such as service animals and medication access needs.

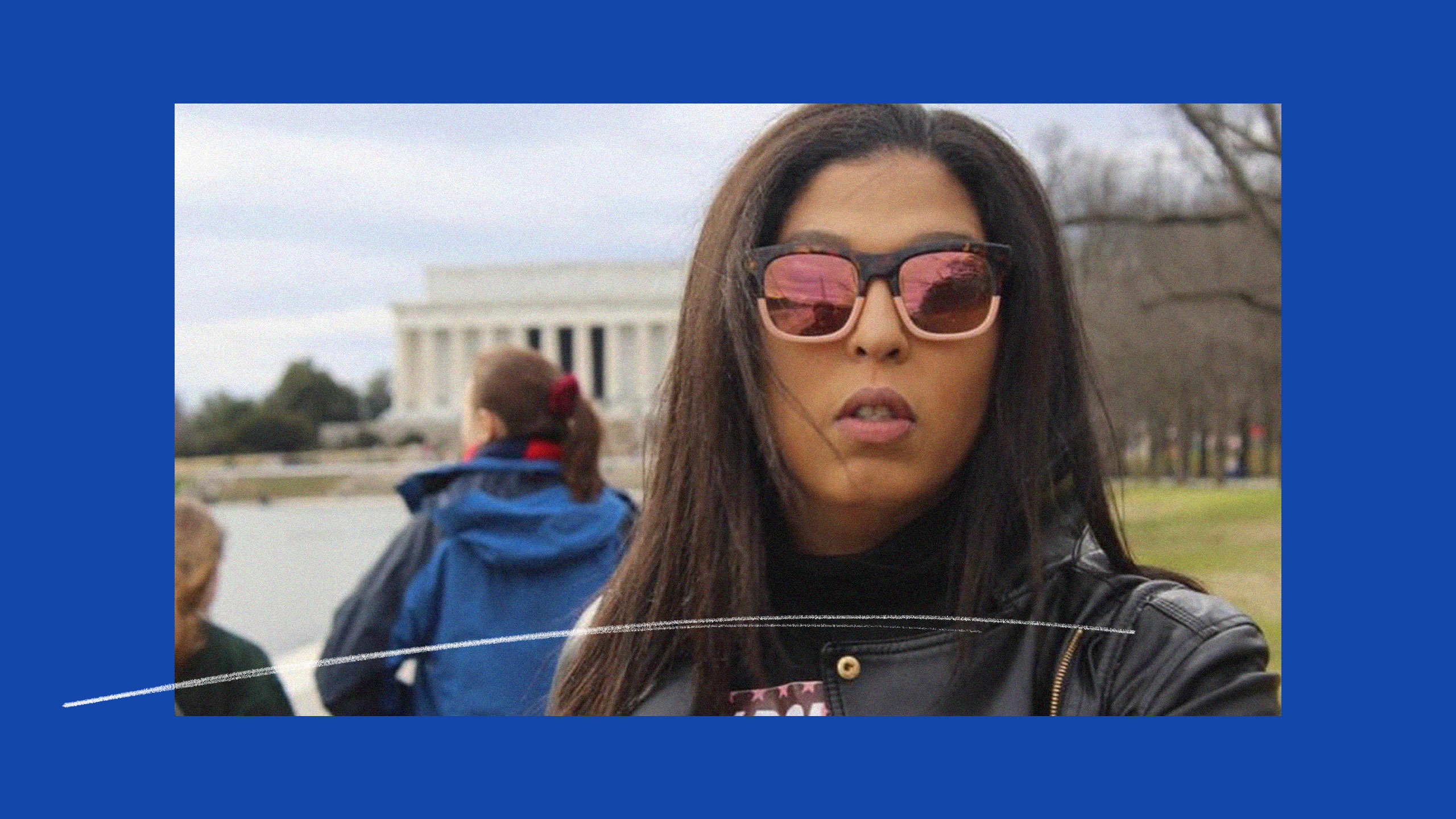

Credit: Courtesy of Mariah Lopez

Lopez, who is an Afro-Latina trans woman, has also been awarded monetary damages for verbal and sexual abuse she experienced while staying at a city shelter.

The road to this victory has taken a gruelling four years for Lopez, who initially launched her suit against the city in 2017 when she was unhoused and experiencing overt transphobia and harassment in New York shelters. At the time, she attempted to seek shelter at Marsha’s House, the city’s only designated LGBTQ+ shelter, but she was initially prevented from entering with her service dog. After a federal judge ordered the shelter to admit her with her dog, she reportedly faced verbal and sexual abuse from staff.

When she complained to the city about the abuse, Lopez was transferred to shelters that weren’t equipped to meet the needs of trans people, ultimately forcing her to live on the street once more.

“I was struggling to survive day to day,” she says. “I was in a desperate situation. And so I learned as I went—but I was not approaching this as someone who knew that I would force the city to somehow reform the entire system. A lot of what I was doing in the very beginning was trying to blow the whistle. I knew that I wasn’t the only one experiencing this.”

Lopez continued to argue the case, serving as her own counsel, while she was living on the street, doing survival sex work and experiencing conditions she says have left her with PTSD. “I do believe the city thought something horrible would happen to me,” she says, “and then I would go away.”

Four years later, Lopez finally gets to see the fruits of her labour as she helps others navigate homelessness. Lopez currently serves as the executive director of Strategic Trans Alliance for Radical Reform, more commonly known as STARR. The organization is a successor to the pioneering work of legendary trans organizers Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson, and one of the oldest trans rights organizations in the country.

Lopez herself is a daughter of Sylvia Rivera, and her activism follows in her mother’s footsteps. “It still feels like I’m holding, waiting for this change. I’m still helping people navigate homelessness,” she tells Xtra, sitting outside a city building where she’s helping a community member process name-change paperwork.

“Everyone deserves safe, dignified housing options.”

Chinyere Ezie, a senior staff attorney with the Center for Constitutional Rights (CRR), which signed on to the case in 2019, says that at the core of Lopez’s activism is an ethos of “all of us or none of us.

“She really brought all of those values to the settlement table,” Ezie, who served as co-counsel in the lawsuit, tells Xtra. “She is an advocate not just for the TGNC community, but for everyone who is experiencing homelessness and forced to sleep on grates and navigate disabilities in New York without proper resources.”

Trans people face an elevated risk of homelessness that is compounded by higher rates of hiring discrimination and income inequality, and they must also reckon with unique barriers in navigating the shelter system. Nearly one-third of trans people have been unhoused at some point in their lives, and 70 percent of those who stayed in a shelter in the past year had experienced some form of mistreatment, according to the National Center for Trans Equality (NCTE). Nearly one in 10 were ultimately kicked out of the shelter for being trans.

Lopez and Ezie know all too well that it’s going to be an uphill battle to get their reforms implemented, but with check-ins and enforcement mechanisms built into the settlement, they will have recourse if the city drags its feet. “Our rights don’t enforce themselves,” Ezie says. “It takes organizing, it takes advocacy.”

Ezie also stresses that the work of Black and brown trans and gender nonconforming activists like Lopez has been instrumental in achieving reforms and changes. “New York state legislatures, decision makers—they are not coming to the table with an understanding of the community’s needs and a willingness to meet them,” she says. Lopez echoes this: “I don’t see a lot of impetus, I don’t see a lot of motivation to do anything but just grandstand from the people in charge.”

But despite these difficulties, Lopez acknowledges that she is lucky to be following in the footsteps of organizers who had less access to legal channels than she does today. “We are lucky to be heard where Sylvia wasn’t heard, and to have our voices acted upon where Marsha didn’t have her voice acted upon,” she says. “This work is really, to me, the legacy of Stonewall.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra