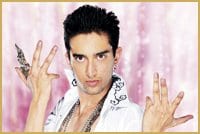

Credit: NIcholas Jang

In his brief 21 years, Omer Pasha has known the bittersweet complexity of living in between. Born into the upper class of Pakistan, he enjoys the privilege, opportunities and financial windfall which accrue to those who occupy a niche in that socio-economic territory. But he also walks the very contentious ground between religion and sexuality. He is Muslim and bisexual in a country where, according to Pasha, “there’s no such thing as being gay.”

Mere months ago, he decided to push the tolerance envelope at the University of Lahore, where as a junior, he performed a striptease routine in a variety show seniors host to welcome new students. The scene for both Pasha and the crowd was surreal.

“There was no applause,” he recounts. “People were just screaming and howling, like they were in shock. They found it flamboyant. People came up to me next day in the cafeteria, all staring at me. One guy asked, ‘so are you gay?’ It was a mixture of curiosity and taunting, but it also felt threatening because he said it in front of everyone.

“I began covering up, saying ‘no, no I’m not.’ And one of my close friends told him it was just a dance. [My sexuality] was a burden on me. I would be looking at guys, staring, and people would notice and say, ‘hey, what’s wrong with you?’ and I would just cover it up. I didn’t know what to do about it.”

Moving to Canada proved to be another exercise in surrealism for Pasha. Alternately checking websites and scouring Vancouver city maps for signs of gay life, he happened inevitably upon the Dufferin Hotel, The Odyssey, and Celebrities Nightclub. He felt at home in those queer hotspots as soon as he walked through the doors, at least in terms of expressing his sexuality.

But in trying to engage people he met in North America about religion and spirituality, he often found intransigence and indifference to faith and belief systems almost as ingrained as the taboos against sexuality that thrive in Pakistan.

“My rebellion here is against people who condemn religion,” he says. “I come across so many people who say, ‘no, no, I don’t believe in God, I don’t care about that.’ But I do care.”

His video trilogy, The Curse, is an attempt to showcase the conflictive interrelationships of religion, sexuality and love. Steeped in the imageries of Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and what he calls “black magic,” it traces, in a style reminiscent of the Bollywood film genre, a young man’s witch-invoked possession that prevents him from recognizing and experiencing true love. But even in his exploration of this theme Pasha, who plays the cursed protagonist, indulges in a game of gender and sexual subversion, surrounding his hero with women who are stand-ins for the true–male–objects of his attraction.

“I deliberately put women in because it would have been too racy to [cast] men,” he says. “I was still in Pakistan, I was in the closet, and still repressed. The women [also] represent homosexuality in that when you are homosexual you can’t get women. They are cursed for you. Homosexuality, in a way, is a denial of lust for women.”

As debatable as that perspective is, Pasha’s invocation in his work is of the major faiths of the day, faiths whose adherents often passionately denounce any sexual expression or identity that does not conform heterosexist norms. But faith healing hurt is the key lesson running through The Curse, says Pasha.

“It’s all in the Qur’an, and it runs through Christianity as well,” he says. “When you have faith, when people are religious, they are always tested. The hurt that you experience in life is the test. A test of the strength of your faith,” explains the young artist whose attempts to get airtime on mainstream Pakistani television for his work turned up empty.

No less then 10 stations balked at running The Curse, elements of which they viewed as sacrilegious. One producer told Pasha if he ran the videos in the more rural, agrarian areas of the country, the effect would be nothing less than riot-inducing.

At issue is Pasha’s liberal blending of homoeroticism with traditional religious symbology. That the witch character, played by Pasha’s mother, wears a stylized Hindu tilaka–variously a decorative, identifying mark or a sign of protection against evil forces worn on the forehead–is considered a no-no in the predominantly Muslim Pakistan. Even more thorny was the inclusion of a burning cross which for Pasha was the exorcism of his heros’ suffering, but is an image historically fraught with controversy.

Reaction to The Curse has been a mixed bag, ranging from one Pakistan-based group’s online threat to kill Pasha to laughter at the other end of the audience feedback spectrum.

“I’m very calm about it,” he says. “It’s art, and people have different interpretations. That’s how the world is.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra