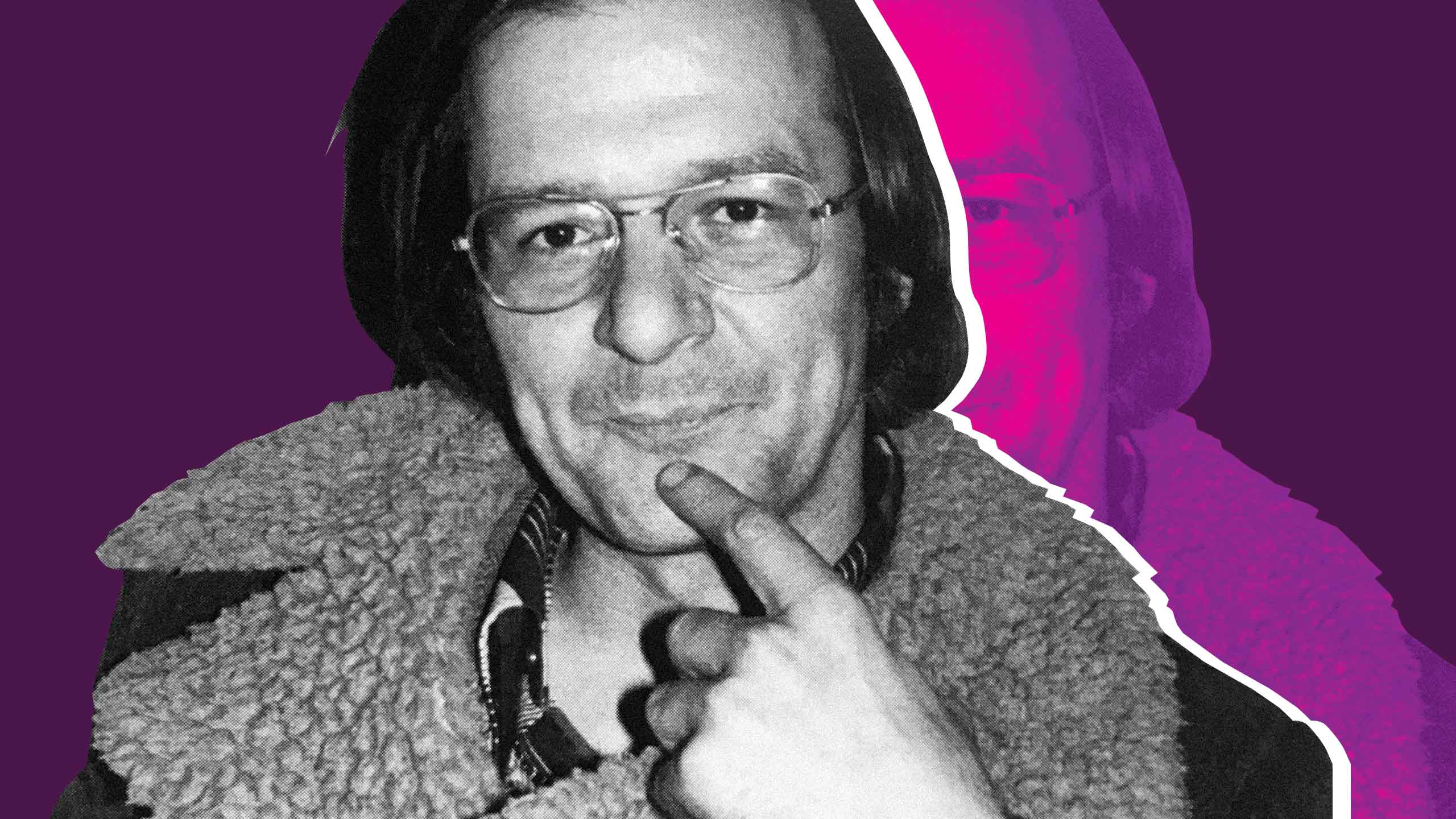

Outside the rarified circles of modern avant-garde music, Claude Vivier’s name barely registers, in part because his life was cut short violently in 1983 in Paris at the hands of a man he had picked up in a bar. Vivier was only 34 at the time of his murder, and just hitting his stride as a composer. Works like Lonely Child and Bouchara, created in the last three years of his life, had finally brought Vivier a measure of success in his home country of Canada and abroad, and they would go on to secure him a place among the great composers of the 20th century.

György Ligeti, a towering figure in music, called Vivier “the finest French composer of his generation.” (If you don’t know Ligeti’s name, you know his music from films like 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Shining.) But the tragic exclamation mark at the end of Vivier’s short life has coloured people’s understanding of him and his music ever since.

The Toronto-based music ensemble Soundstreams has made it their mission to promote Vivier’s work and foster a critical reappraisal of his oeuvre. This week at Toronto’s Koerner Hall, the group will present two of Vivier’s works, Love Songs (1977) and Hymnen an die Nacht (1975), along with the premiere of a new commission inspired by a lost work of Vivier’s, Oceano Nox, by Toronto composer Christopher Mayo. (The filmed concert is available to stream beginning at 8 p.m. ET on Nov. 19; tickets can be found here.) And in the spring, Soundstreams will embark on a European tour with a staged version of Vivier’s Musik für das Ende (1971), with another tour on the books for the following year.

“Unfortunately, Canadian music is not so well known internationally,“ says Soundstreams founder, oboist Lawrence Cherney. “As a Canadian organization touring internationally, we wanted to have something that would open doors. And Claude opens doors, particularly in Germany, Netherlands and Belgium.”

“Vivier’s music may seem weird at first because, well, much of it is.”

To the uninitiated, Vivier’s music may seem weird at first because, well, much of it is. Love Songs, for example, which opens Soundstreams’ November concert, begins with soloists shrieking the names of Tristan and Isolde as other singers frantically wobble their tongues back and forth as they sing. (It’s a wild 12-minute ride but stick it out, if you can; the rewards are many.) In other pieces, singers distort their voice by drumming their fingers on their throats or waving their hands in front of their mouths. Many of Vivier’s compositions feature a made-up language. These innovations represent both a child-like element of play and a sophisticated understanding of our relationship to voice—how, for example, we often understand sung words not by comprehending them per se, but by how they make us feel. Like a mother talking to a baby or a congregant listening to a Latin mass, the pathways to communication are many.

Mayo says Vivier had a profound impact on his own musical development, particularly the hauntingly beautiful Lonely Child, but that was only after encountering Vivier’s work while overseas. “I only really discovered his music when I left Canada and went to study in the U.K,” says Mayo, who has degrees from the Royal College of Music and Royal Academy of Music.

“I had never heard any of his music. I had never heard of him at all—which, at the time, I blamed on a poor undergraduate education. But I think I was just a poor undergraduate,” he says, laughing. “I was in the U.K. for about 11 years, and in all that time, Vivier was the only Canadian composer most people had ever heard of or encountered.”

Viver was abandoned as a child and abused; he remained poor his whole life. But he gained a reputation as a fun-loving trickster who was unfailingly passionate about music and music theory. He was flamboyantly gay at a time when few dared to be so open (homosexuality was only partially decriminalized in Canada in 1969). Obsessed with his origins, Vivier composed music that sighs with nostalgia for lost meaning. He thought long and hard about how people communicate, whether through dialogue, music or other means, and he was fascinated by ritual and the mental states that music can evoke. Vivier travelled to Japan and South East Asia to experience different forms of ritualistic music firsthand. To reach music’s deeper structures, he scrambled the surface sounds and recombined them in fascinating and complex ways.

“I think the reactions that you have to it, whether it’s amazement or laughter or confusion, those are the intended ones,“ Mayo says. “That’s how you can engage with it. Just let yourself react to it, honestly.”

In other words, it’s okay to laugh when you hear the wobbly sounds for the first time. There’s a directness in Vivier’s music there for the taking. But that directness, that simplicity, is not always apparent: it’s elusive, it’s complicated.

“There’s a lot of earnestness there, but it’s shrouded under all these other layers of different kinds of narrative, different kinds of interaction with an audience. He’s playing with sincerity, insincerity, sarcasm,” Mayo says. “There’s a full array of ways of communicating that you have to pick apart to find meaning in.”

Composer and musician David Jaeger knew Vivier through his decades-long work at CBC Radio (Jaeger was the original producer of the contemporary music program Two New Hours that ran from 1978 to 2007). “I’m personally of the strong opinion that Vivier revealed himself to himself through his invented language. Things that were too painful for him, too troubling to say in an understood language, he would express [with invented words] just to get them out.”

Is it too reductive to think that Vivier made complicated music in part because his life was complicated?

Born in 1948 in Montreal, Vivier knew nothing of his birth parents; he was placed as an infant in one of the city’s larger religious orphanages, La crèche Saint-Michel. He was two and a half when adopted by the Viviers, a poor working-class family who promptly returned him to the orphanage. Claude Vivier’s biographer, Bob Gilmore, thinks that young Claude may have been too rambunctious for Mrs. Vivier, who was housebound because of a nervous ailment. Eventually, however, the adoption took hold, and Claude was brought to live with the Viviers in the small house they shared in what was then a hardscrabble neighbourhood in Montreal’s Plateau area.

At the age of eight, Vivier was raped by an uncle who lived on the ground floor. Vivier told a priest during confession, who demanded that he tell his parents. Vivier eventually informed his mother. We don’t know when but, according to Gilmore, the disclosure ended up being a black mark against the young boy. The family moved house and Vivier was sent away to live in a series of boarding schools run by the Marist Brothers.

Reflecting on his childhood in the late ’70s, Vivier wrote:

The fact of knowing from the age of six that I had no father or mother gave me a marvellous dream universe. I fabricated my origins as I wanted, and pretended to speak strange languages. The reality that I encountered every day was that of a very hard kind, muscular. I wasn’t left alone to dream of these marvellous lands and these charming princesses; the reality I encountered was only violence and pettiness.

In the 2014 biography Claude Vivier: A Composer’s Life, Gilmore shows how the Catholic secondary schools, or juvénats, that Vivier attended were his salvation, offering a level of education he wouldn’t have got elsewhere. In particular, they provided him with a strong introduction to music through the schools’ many religious services. Vivier was a serious student with a facility for languages, learning Latin and Greek. He was also a precocious classmate, a somewhat clownish figure looked upon with affection by instructors and other students.

At 17, he enrolled in the Noviciat des frères Maristes in Saint-Hyacinthe, east of Montreal, and considered becoming a brother. The maître des novices, however, felt Vivier unsuited for a religious vocation, and pushed him out of the school and into the wider world. (Whether there was some sexual impropriety at the heart of the maître’s decision—and whether it was on the part of Vivier or a brother or both—is a strong possibility, according to Gilmore.) But by the time he was 18, Vivier knew that his real calling was to become a composer.

He enrolled in Montreal’s Conservatoire de Musique, and later studied for three years abroad—first at the Institute for Sonology in Utrecht, Netherlands, and then in Cologne, Germany, with composer Karlheinz Stockhausen. He returned to Montreal in 1974, determined to make a go at being a freelance composer.

The 1960s and ’70s were a time of tremendous experimentation in music. The legacy of early 20th century avant-garde composers like Schoenberg still held sway. But new schools based on how tones and harmonies are made were gaining traction, in part because of new technologies; electronic music and computer-generated sounds were beginning to fire the imagination of many composers. You don’t necessarily need to know that Vivier was moving away from something called serialism and embracing his own idiosyncratic approach to something called spectralism to understand his music. Suffice it to say, he had the intellectual chops to impress the most eggheady music nerds while producing works that were anything but austere or cerebral.

“Vivier was brilliant enough to comprehend all of the theory, but he never let the theory stand in the way of self-expression,” Jaeger says. “His was a unique voice that had both complexity and clarity.” Simple yet sophisticated is how Ligeti characterized Vivier’s music, saying it offered “maybe the richest thinking in sound.”

Bold and boisterous, Vivier was a striking presence (and an often disruptive one) among bohemian circles in Montreal. He was devoted to his friends, a feeling that was reciprocated, even if they found him exasperating on occasion. “Nothing he ever did was predictable,” Jaeger says. “When he was excited he could not hold back. He just loved to talk about himself.”

Vivier was out as gay from the get-go, swanning about town in a smelly sheepskin jacket and long hair. Whether at a seedy bar or high-toned concert, his piercing laugh—or often a loud yawn—announced his presence. If sex broke out at a party, he was in the thick of it. (He once commended Germans on how well they conducted orgies, but felt that, ultimately, Montrealers did them better.)

“Nothing he ever did was predictable. When he was excited he could not hold back.”

Not only was Vivier out in public, but he was out in his compositions. Viver’s Journal (1977), for example, includes the lyrics, “I searched all over the city to find you/ And your sex is still throbbing in me.”

“He never hid it,” Cherney says. “He was openly gay. That was extraordinary at that period of time.”

Moreover, Vivier contemplated how his sexuality contributed to his work, something thats rare among classical composers now, let alone back in the 1970s. In response to criticism that his 1978/79 opera Kopernikus lacked drama, Vivier expounded on what he thought “gay music” might be in an interview with Montreal’s gay magazine Le Berdache. He described opera’s dependence on action and drama as “male discourse” and a “macho complex.”

Citing feminist theorist Annie Leclerc, Vivier celebrated the emergence of new paradigms. “When I talk about gay discourse in that sense,“ he told the reporter, “a gay discourse, as much as a feminist discourse, is a way of putting people on an equal footing without discrmination.” The vantage point of a gay man, Vivier argued, “transcends” the particulars of sexual expression and sets him on a path of discovery that’s hidden from his straight compatriots.

“His openness and boldness at that time and in those places and in those spaces—to carve out a space for himself—he clearly felt so much joy and exuberance,” Mayo says. “I don’t think he was at all concerned about fitting into anything. He was just going to sing his song. And he did.”

That joy and exuberance were soon to be overshadowed by the shocking details surrounding his death.

Vivier had a well-known penchant for rough trade and SM sex. But his sexual preferences took on an outsized role in people’s understanding of him after a pick-up strangled and stabbed Vivier to death in a Paris apartment in 1983. His body wasn’t discovered for a number of days. The 19-year-old assailant was eventually caught and convicted; Vivier was the third gay man he had killed.

The lurid aspects of his death became fodder for a lot of moralizing. It didn’t help that one of the last pieces he composed while in Paris, Glaubst du an die Unsterblichkeit der Seele? (“Do you believe in the immortality of the soul?”), describes a character named Claude cruising a handsome young man on the Metro. The unfinished work stops with the line: “Then he removed a dagger from his jacket and stabbed me through the heart.“

The myth of the doomed genius chasing death was born.

“When someone has such a tragic and dramatic end, it’s so hard not to fall for the trap of refracting all of their life through that,” Mayo explains. “But it’s a slightly sneering puritanical view.

“Early on the way that I saw it was: Composer with a sad story wrote a sad song,” Mayo says, in reference to Lonely Child. “There’s something appealing and easy to market about that.“

Music writer Paul Griffiths, who has written repeatedly about Vivier’s work with great sensitivity, epitomises that framing. “Claude Vivier,” Griffths wrote in the back cover blurb for Gilmore’s book, “lived a life we had thought extinct: that of the doomed creative genius, casting off masterpieces from an unstoppable ride into the abyss.”

Cherney hopes to dispel some of the gloom by offering listeners a chance to hear Vivier’s work afresh through his lesser-known works. “Only maybe five or six of 49 works are reasonably well-known,” he says. “There are quite a few works of Claude’s, including the one we’re touring to Europe, Musik für das Ende, which were never staged during his lifetime. Nobody knows that piece. It tells us a lot about where he went later in terms of composition. And also his later compositions shed a lot of light on what he was trying to do in his earlier pieces.”

Soundstreams’ Vivier performances, he concludes, “offer an incredible voyage of discovery.”

“Vivier had a certain fame or notoriety because of the way he was murdered,” Cherney says. “Slowly but surely, we’re beginning to realize that despite his amazing backstory, underneath it all, there was actually a composer of tremendous substance.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra