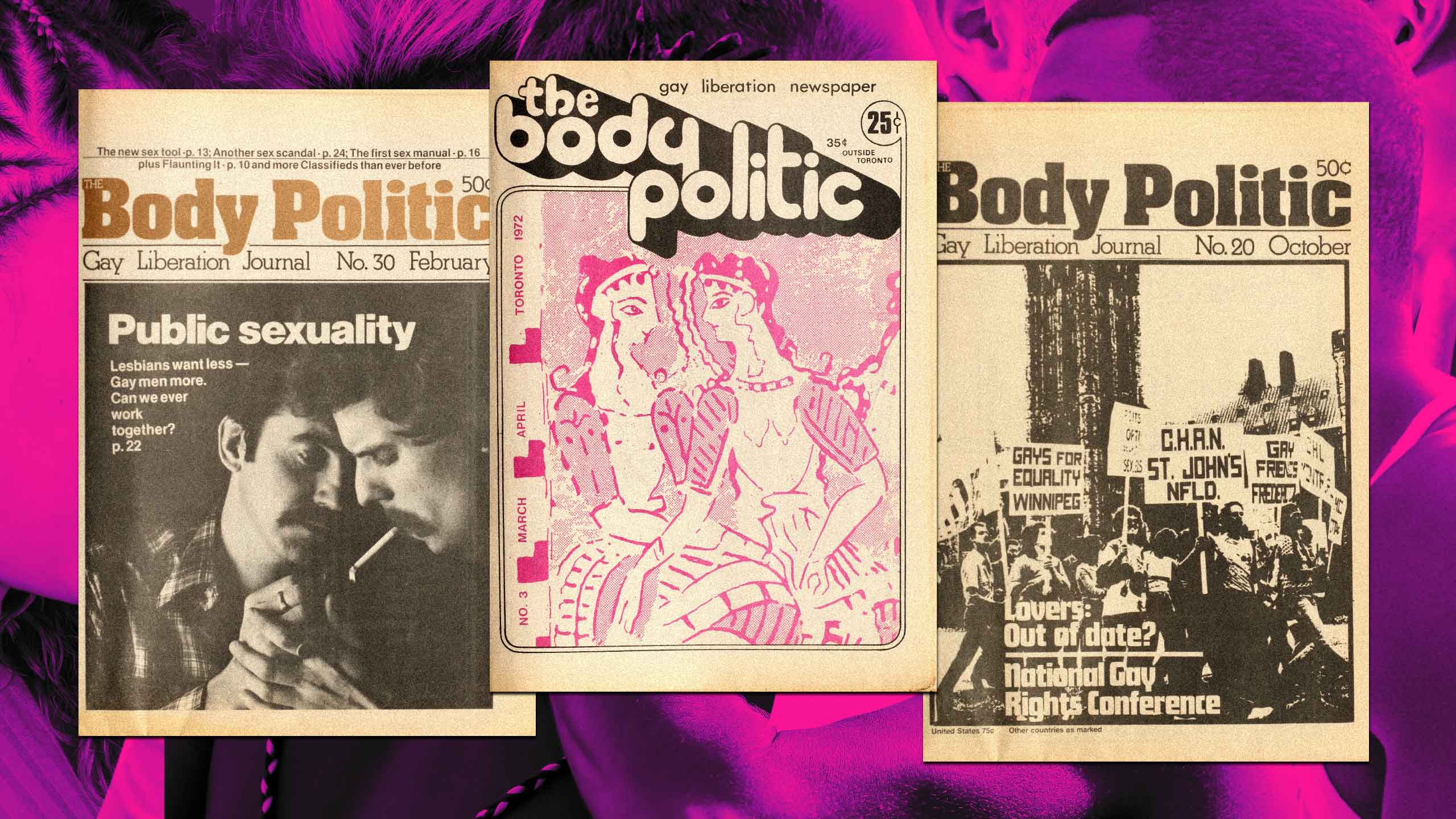

In 1971, a group of young radical activists in Toronto got together to launch a revolution: A collectively-run, unapologetically gay newspaper called The Body Politic. It was two years after the Stonewall uprising in New York City and a year after amendments to Canada’s Criminal Code partially decriminalized homosexual sex. It was the dawn of a new era.

The 1970s gave birth to the modern LGBTQ2S+ movement—though back then it was called “gay liberation” or sometimes “gay and lesbian liberation.” The community established advocacy groups and support networks, opened gay bookstores, community centres and dance clubs and launched the first Pride Day celebrations to mark the anniversary of Stonewall. After centuries of persecution and shame, our communities were coming out of the closet, proudly embracing who they were and fighting for the right to live and love as they desired.

In 1972, Sweden became the first country in the world to allow trans people to legally change their sex. The following year, the American Psychiatric Association removed “homosexuality” from its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; and in Toronto, Canada’s first lesbian conference was held at the YWCA. In 1977, Harvey Milk became a San Francisco city-county supervisor and the first openly-gay American to be elected to public office; a year later he was assassinated alongside Mayor George Moscone, and his prophetic quote rang out in vigils honouring him: “If a bullet should enter my brain, let that bullet destroy every closet door.” A thrilling new sense of fury, pride and freedom emerged, in the streets and in the clubs, where gay anthems like Sylvester’s legendary 1978 hit “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)” formed the soundtrack for gay liberation.

The Body Politic collective covered this bold new movement and culture with an eclectic mix of reportage on civil rights campaigns, lengthy digressions on literature and art, candidly horny articles on sex and scholarly essays on gay history, which held a significant interest for the collective. In 1976, it created the not-for-profit media group Pink Triangle Press (which is Xtra’s publisher) taking its name from the insignia that homosexuals were forced to wear in Nazi concentration camps.

The Body Politic was sex positive, audacious, outrageous, provocative and infamous. The collective often found itself at the centre of the action it was covering—in court battles over freedom of the press and censorship after its office was raided by police, and in protests against state oppression. (For vivid accounts of The Body Politic’s early years, read collective members Gerald Hannon on the publication’s first decade and Tim McCaskell on the early history of the gay liberation movement.) In February 1981, The Body Politic was at the front lines of the protests against a series of brutal police raids at gay bathhouses in Toronto. That October, the paper ran its first story on HIV/AIDS: An article headlined, “Gay Cancer? Or Mass Media Scare?”

Activism, sex and outrage didn’t make for a solid business plan, however. Searching for new sources of revenue, Pink Triangle Press (PTP) launched Xtra as a local entertainment guide in Toronto in 1984. The press suspended publication of The Body Politic two years later, to focus on Xtra and other media endeavours: Local gay newspapers, a dating site, a travel show, among others. Turning 50 this fall, PTP is one of the world’s oldest LGBTQ2S+ media groups and it remains, as it always was, independent, queer-operated and queer-run.

“What does sexual liberation mean for our communities in 2021 and beyond?”

To mark this milestone birthday, we decided to revisit the concept of sexual liberation, one of the press’ guiding values since it launched The Body Politic a half-century ago, and consider what sexual liberation means for our communities in 2021 and beyond. In the six-part series for Xtra called “Protest and Pleasure,” beginning May 17, scholar and activist Chanelle Gallant talks with LGBTQ2S+ activists, thinkers and creators involved in movements for social and economic justice—disability justice, sex workers’ rights, police abolition, Indigenous sovereignty, economic justice and migrant rights—about the connection between their work and sexual liberation. Good sex, it turns out, requires better activism.

To kick things off, I spoke with Gallant about her series and the issues she will be tackling.

Let’s start with language. The term “sexual liberation” sounds old-fashioned and cringey to me. I think of a straight dad at a key party in the 1970s with his polyester shirt unbuttoned to his waist and a lot of bad cologne. What about you?

I think the language of sexual liberation is pretty unappealing and I don’t really even use it. From what I can tell, the idea was dominated by straight white men who basically defined “sexual liberation” as the freedom to have sex with any women they want. It’s individualistic and it drains the concept of any of its politics—and, honestly, any of its sex appeal.

Still, we could use some sexual liberation right now, because we have major problems in that realm: Coercion, harassment, sexual violence. Every marginalized community has to deal with being sexually stereotyped. There’s homophobia and transphobia. We don’t have equitable access to sexual and reproductive health care. And we have millions and millions of people on medications that have sexual side effects. But good luck getting competent sexual health care from a doctor, especially if you’re queer or disabled.

What’s replaced the language of “sexual liberation” now is the language of “sexual consent.” Consent is now how we talk about power over our sexuality. But my concern is that the way we use the concept of consent is still very individualistic and often apolitical. That’s not going to solve our sex problems.

Like the way consent is often presented as good etiquette, or a straightforward negotiation between two individuals.

Or like it’s all about granting or revoking sexual permission. That doesn’t at all capture the social, economic and political issues that we have with sex.

Consent is collective. It’s the result of structural power. We talk about the social determinants of health, and we should similarly talk about the social determinants of consent. Think about how people with a lot of social power and money have oodles of sexual freedom. They have their boundaries respected. They are not reduced to their sexuality. Their sexual health is more understood and they’re just more able to get what they want from sex.

Compare that to a highly marginalized person with little agency and power, like a trans kid in foster care. They have to fight tooth and nail to have control over their sexuality, including freedom from sexual harm. People with less social power have less control over their sexuality.

One of the failings of the gay liberation movement of the 1970s and 1980s was its lack of diversity. Like the gay liberation movement itself, The Body Politic collective was largely white, gay and cis male. The result is that much of the gay liberation movement and discussions around it had a narrow focus on a very narrow version of sexual freedom. It often overlooked or dismissed race, gender identity, sex, class, disability. How do we bring an intersectional approach to sex?

Look, I was forged out of ’90s sex radical politics and I still owe a lot to queers who fought to free queer sex. Also, a lot of those views were actually quite white, middle class and liberal. Many saw sex as separate from white supremacy and capitalism; they thought we could liberate sex without addressing the racist police system or our ruthless economic system, for example. And I have spent two decades learning that that’s not how sexuality works.

Our sexualities are bound up together in the world created by those injustices. Sexual liberation requires collective liberation. That’s why I’ve been wondering about using the concept of “sexual justice” as a more helpful way of talking about the connection between sex and politics.

“Sexual liberation requires collective liberation.”

One of the ideas I want to explore in this series is mutual interest. How would having racial, gender and economic justice liberate sex for everyone? I wanted to talk to some of the most brilliant LGBTQ2S+ activists, thinkers and creators who are working on the front lines and ask them. So far, the conversations have been beautiful and surprising and I can’t wait to share them with Xtra readers.

Following the height of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 1990s, there was a shift in LGBTQ2S+ activism towards court and legislative battles for marriage equality and domestic partnership protections. This focus made sense: During the crisis, people were banned from visiting their lovers in the hospital or attending their funerals. You can understand why legal protections for our relationships felt so important. But I wonder about the consequences of having put so much of our focus here.

First, I want to say that shitting on marriage is a radical queer pastime, which is fine, but I’m not going to rehash those arguments. I think marriage is a complex issue for people who’ve had to fight for control over how they form families—and that’s certainly not limited to queers. Think about histories of enslavement and settler colonialism and how power is exerted over how people form intimate relationships.

Having said that, what’s interesting to me in looking at the queer movement for marriage is how deeply we’ve normalized the fact that many of us can’t really survive capitalism without sexual relationships. Behind all the “love is love” rhetoric is the fact that marriage is both a sexual relationship and also one of the only ways that adults share money and resources with other adults.

Marriage has always tied sex to money. People get married because they want to access their partner’s health insurance, which is especially important for sick and disabled or trans people. Or they stay married because they can’t afford housing or raising their kids on their own. But those are all basic needs. Those are life and death needs, that many people can only meet by entering into a state-sanctioned sexual relationship. That’s the capitalist state undermining our consent.

And that brings us back to sexual justice. How consenting are we, really? How free are we when being single means you can’t afford to meet your basic needs? So when the state ties sex to our survival, we’re in essence being coerced into certain types of sexual behaviour. This is why I say that sexual freedom is about social and economic justice. People should have the things they need to survive, like housing, child care and health care, so that they’re free to engage in sexual relationships on their own terms, not out of economic need.

Last question: What kinds of conversations do you want to spark with this series?

I’m hoping Xtra readers will be excited to talk about sex and social and economic justice because right now, I don’t think we have a very radical imagination when it comes to our sexuality. I want more conversations about sex that redefine it as the product of collective struggle for power. What would be possible if we actually freed sexuality? What would be possible if sexuality was actually ours? And beyond more conversation, I want more action. I want more queer folks to understand that their sexuality is at stake in the fight for social and economic justice. I want to seduce people into activism, always.

Let us know your thoughts. What are your questions and ideas about sexual freedom and sexual justice? What would you like Chanelle Gallant to talk about in this series? Email insidextra@xtramagazine.com. Please check out the first five instalments in the series, here.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra