Little Sister’s decades-long legal battle with Canada’s border cops has hit another wall — and it looks like this one may be insurmountable.

On Jan 19, the Supreme Court Of Canada rejected the Vancouver queer bookstore’s bid for advance costs to help fund round two of its struggle against Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA, formerly Canada Customs) and its ongoing seizures of gay materials they deem obscene.

“This decision means the Charter Of Rights And Freedoms [is] only available to the rich and powerful in this country,” says Kaj Hasselriis, interim executive director of national queer lobby group Egale Canada.

Though the BC Supreme Court had granted the store’s funding request in June 2004, the BC Court Of Appeal overturned the order in February 2005. The Supreme Court sided with the appeal court, ruling that the Little Sister’s case is not special enough to warrant the rare advance costs order.

“The four books appeal, in which [Little Sister’s] alleges a discriminatory attitude on the part of Customs to some of its merchandise, is extremely limited in scope,” Justices Michel Bastarache and Louis LeBel wrote for the court’s majority. “Public-interest advance-costs orders must be granted with caution, as a last resort, in circumstances where their necessity is clearly established. The standard is a high one: only the ‘rare and exceptional’ case is special enough to warrant an advance costs award…. In the present case, the issues raised do not transcend the litigant’s individual interests.”

The ruling leaves Little Sister’s without the money to hold CBSA accountable in court.

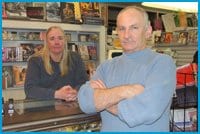

“We have to put our case to bed and declare defeat,” says Little Sister’s co-owner Jim Deva, who now expects seizures of queer material to ramp up again within a few weeks.

“By admitting defeat, we have told them they have unlimited power,” he says. “God help us.”

The case stems from a complaint Little Sister’s filed against Canada Customs in 2001, after border guards seized copies of several SM comics, labelling them obscene. Little Sister’s challenged the obscenity designation, and claimed the new seizures show the agency is still discriminating against its shipments — despite the Supreme Court Of Canada’s 2000 ruling ordering them to stop unfairly targeting queer imports.

The SM comics case was to be heard in BC Supreme Court, but as the parties began to outline their cases, it became clear to Little Sister’s that it couldn’t afford to counter the government’s extensive expert list without some financial help. So it asked for advance costs, based on a 2003 Supreme Court precedent called Okanagan that granted an aboriginal group funding to take the government to court.

“The situation in Okanagan was clearly out of the ordinary,” the majority wrote in the Little Sister’s ruling. “The bands had been thrust into complex litigation against the government that they could not pay for, and the case raised issues vital both to their survival and to the government’s approach to aboriginal rights.”

But the court ruled that the public interest in the Little Sister’s case is insufficient to justify the government footing the bill.

“What the court has done is failed to recognize that this is a systemic problem,” says Cynthia Petersen, the lawyer who intervened in the case on Egale’s behalf. “The majority judges seemed to think this is about four books.”

Justices Ian Binnie and Morris Fish dissented, writing that they would have granted Little Sister’s $300,000 in advance costs. Systemic discrimination by agency officials “and unlawful interference with free expression” were clearly established in the first Little Sister’s case, they wrote.

“In its application for advance costs in this case, [Little Sister’s] contended that the systemic abuses established in the earlier litigation have continued, and that Customs has shown itself to be unwilling to administer the Customs legislation fairly and without discrimination.

“The question of public importance is this: was the minister [in charge of Customs] as good as his word in 2000 when his counsel assured the Court that the appropriate reforms had been implemented?”

Considering that 70 percent of the agency’s detentions are of gay and lesbian material suggests there is “unfinished business of high public importance left over” from the first Little Sister’s case, wrote Binnie and Fish.

The decision shows that the little guy has little chance against the big money the government can throw at such cases, says Deva.

“We can no longer pass the bucket around and think we can meet the costs of court cases.”

With the federal Court Challenges Program gone and the costs of mounting cases against the government escalating, the advance costs option offered one last “little window of hope, and that is clearly closed now,” Deva says.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra