I often think about the generation of Black queer excellence we lost during the height of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and ’90s, those men, women and people who should still be here to see how the paths they paved are a blueprint for generations that may or may not know their names. What might our lives as young Black queer creatives be like if we could touch and talk to those foreparents?

This question, for me, persists, and even more so in light of the Sundance premiere of Ailey, a documentary about the titan of modern dance and namesake of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. A moving portrait about a man whose genius transformed an industry, the Jamila Wignot-directed film pulls back the curtain—ever so slightly—on a life of impact cut short.

Ailey was filmed in the lead up to the 2019 premiere of “Lazarus,” a dance created for the company by hip-hop choreographer Rennie Harris inspired by the life and legacy of the legend himself. Featuring a host of interviews with former dancers and company associates—including Judith Jamison, George Faison, Sarita Allen and choreographer Bill T. Jones—the doc splices “Lazarus” rehearsals with archival footage of the Deep South, ’70s-era New York City and classic Ailey dances (including rare, original performances of some of Ailey’s most famous works). All the while, Ailey himself narrates the film via audio from interviews during his final years. The result is an enveloping, emotional experience that dancers will surely appreciate but everyone can enjoy. It’s also a warning, for Black creatives and beyond, of the perils of Black genius and exceptionalism, of what can happen when the burden of success becomes intoxicating and our work becomes bigger than ourselves.

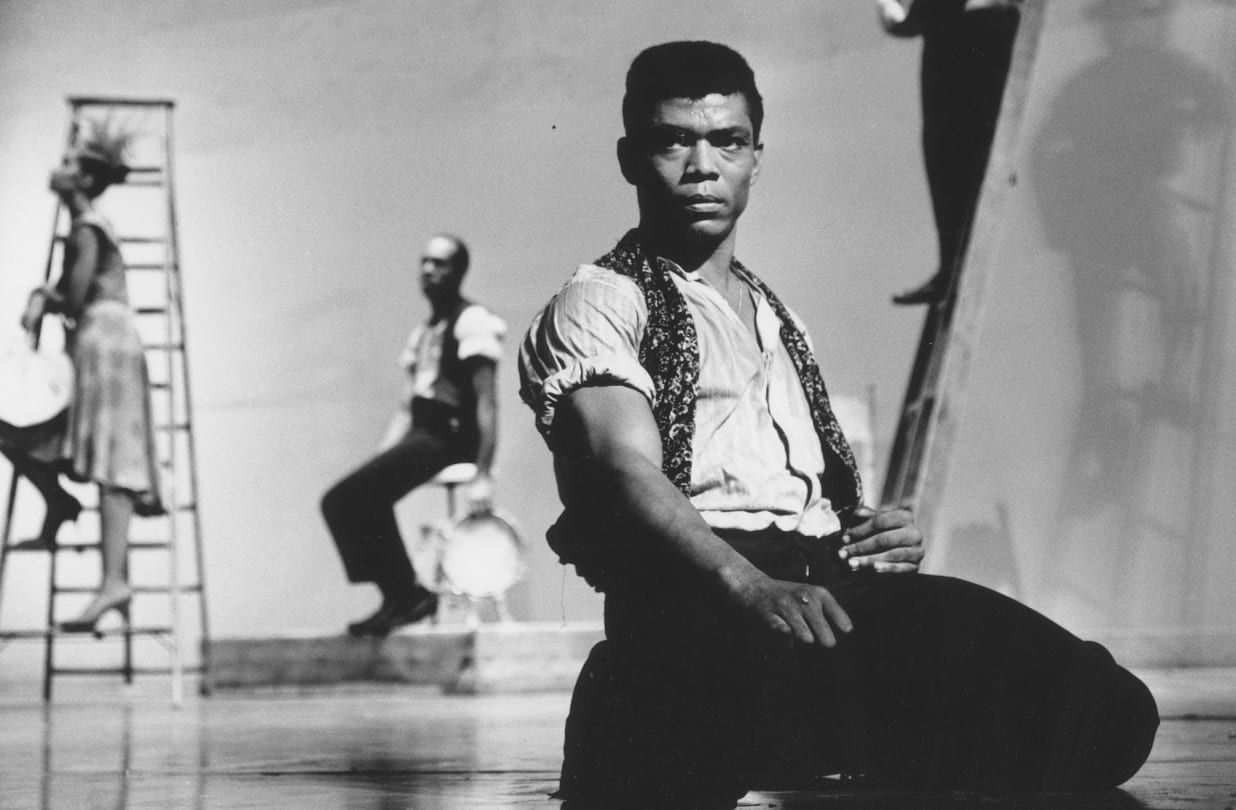

Credit: Jack Mitchell/Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation/Smithsonian Institution

Ailey was born in 1931 at the height of the Great Depression to a young mother in Rogers, Texas. He was raised against a backdrop of racial segregation and violence. In 1942, they moved to Los Angeles, and at age 18, Ailey began taking dance seriously. At 22, he formally joined Lester Horton’s company, the first multiracial dance school in the country, where he became artistic director less than a year later when Horton died. After a stint performing on Broadway, Ailey founded the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in 1958 as a way to preserve the uniqueness of the Black American cultural experience; he wanted to use it to transform what modern dance could be. The theatre would go on to become one of the leading dance companies of the 20th century.

As the documentary chronicles this journey, it’s endearing to hear from Ailey’s contemporaries and collaborators who witnessed the ascent in real time. Perhaps most impactful, though, are the observations Bill T. Jones provides as a Black gay man reflecting on one of his own possibility models. In describing the weight of Ailey’s genius, Jones details a particular seclusion Ailey experienced. He suggests that despite how successful Ailey was, he felt unworthy of the accolades and perhaps guilty that he was living his dreams. And though Ailey had a community at his disposal, he remained a severely private person with no lasting romantic partner and no one, even in the film, who could fully speak to the man beyond his gifts of dance and choreography.

To that end, if I had to say anything was missing from Ailey, it was the lack of interaction with the generation of dancers who are his living, breathing legacy. I wanted to hear from the Black gays beyond Jones who are carrying on his memory, quite literally, through the use of their bodies. Still, it is in Jones’ reflections that I think Ailey is most useful, turning what is a solid tribute to an iconic dancer and choreographer into a cautionary tale for Black creatives.

We don’t talk enough about the tax of being deemed exceptional. We don’t talk enough about the burden shouldered by those whose genius helps them claw their way to success and the resulting obligation for it to sustain them. And we don’t talk enough about the ways in which our own actions, though influenced by our circumstances, can sometimes make us complicit in our own suffering.

“We don’t talk enough about the ways in which our own actions, though influenced by our circumstances, can sometimes make us complicit in our own suffering.”

Jones offers that perhaps Ailey’s name became so big that it outweighed the man himself, that it robbed him of a certain level of vulnerability, of a humanity that might’ve made him more than what history books have ascribed to him. Though Ailey came alive on stage and in rehearsals, using his work as a site of protest, self determination and reclamation, it’s the seeming lack of life offstage that’s disappointing.

And yet, both the film and Ailey, in ways unspoken, advise us on what we can do differently: Establishing our worth outside of our work, cultivating a community rooted in unconditional love, rejecting the pedestals the white world often wants to put us on. This is not to say Ailey didn’t do these things, to be clear. Rather, what the doc offers is a commentary on how getting to the top of one’s professional pursuits is only half the battle; we must invest in ourselves just as fiercely.

It’s a joy to see Ailey’s impact receiving its due beyond the hallowed halls of dance schools and performance venues. In addition to this doc, Moonlight’s Barry Jenkins is supposed to be directing an Alvin Ailey biopic, written by Julian Breece. Each project, without a doubt, is a flower we lay at the feet of Ailey’s memory, a way of thanking him for everything he gave. I just wish he was still here to smell them.

UPDATE/AUGUST 6, 2021: Ailey is now playing in select theatres. Please check local listings.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra