This is one of the last stories RM Vaughan wrote. Our friend and colleague died earlier this month. For those who knew and cared for Richard, this may not be an easy read. But one of the last messages we received from him the week before he died expressed his eagerness to get this story published. He cared deeply that the legacy of Canadian writer Timothy Findley be remembered and that the hard work of biographer Sherrill Grace be recognized. That was Richard: Always thinking of the artist. And the art. And the words. Reading Sherrill Grace’s rich, layered biography of iconic queer Canadian writer Timothy Findley, Tiff (titled after Findley’s nickname), I found myself constantly reminded of how difficult it was to be a queer artist only a generation before my own. Like any gay man in his 50s, I’ve banged my head on the lavender ceiling plenty of times. But the cruel homophobia Findley experienced, survived and thrived in spite of really kicked me in the soft parts. In the first full biography of Findley, we learn that he came out to his family in 1944 while growing up in the then-very Christian and very conservative Toronto, some 25 years before homosexuality was decriminalized. That pivotal decision changed his life. As Grace writes, Findley’s father was appalled (and remained aggressively so for decades), his brother derisive and his mother deeply worried. “Timothy Findley’s coming out to his parents was a remarkably brave thing for a fourteen-year-old boy at a time when homosexuality was a social disgrace and a crime.” When Findley developed an interest in dance, his father remarked, “I’ll be damned if I will pay for ballet lessons for a son of mine.” Years later, the critical reaction to Findley’s first books (published outside of Canada because no Canadian publisher would take them) echoed the sentiments of his family. Critics found his realistic depictions of artists too crude and too alarmingly real. His 1967 novel The Last of the Crazy People was derided for presenting middle class children who are (no spoilers!) less than perfect. One critic described Findley’s writing as derivative of U.S. writers and made of “unrelieved gloom,” which I read as code for the “sad homosexual” stereotype. For much of Findley’s early career, his books were difficult to find in Canadian bookstores. But by the time he passed away in 2002 at the age of 71, his novels, plays and short stories had earned him everything from a Governor General’s Award for fiction to membership in France’s prestigious l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. His stellar career spanned five decades and he published over two dozen books, including now-canonical CanLit masterpieces The Wars, Not Wanted on the Voyage and The Stillborn Lover. Tiff will make you cry, and you’ll be glad for the experience because Findley broke the rules—and even the law by being an out gay man in the mid-20th century—and paid a terrible price. But also because he fought back, worked hard and left behind a legacy that has already outlasted his nemeses. Sometimes we forget about the struggles of our queer cultural ancestors, the people who got us to where we are today, because it’s so damned hard to keep all that pain in your head. But Tiff is too deep a dive to be read only as a reminder of the “bad times.” Findley was a consummate artist. He wrote and wrote and wrote, grew in popularity and built a beautiful life for himself and his partner. The genius of Grace’s biography lies in the balance it strikes between marking Findley’s stellar rise while never forgetting the trauma and psychological violence that both fuelled and haunted his creativity. Nor their opposites: Grace beautifully recounts Findley’s deep love for Bill Whitehead (his lover of many years), his loyalty to his intimate friends, his devotion to animal rights and conservationism and, always, his fearless embrace of the daily work of writing. Findley lived and wrote while battling a relentless interior “fear of failure and death,” Grace says. Conversely, Findley spent his public life performing the role of the amiable celebrity, a performance he used to protect himself, and one that Grace says came naturally to him. Given all he had to overcome in his youth and young adulthood, Findley’s creative life was scarred by the threat of erasure. Happily, he lived to see that threat turn to dust.

Chatting with Grace online, I learned that while Findley’s life was profoundly affected by the pervasive homophobia of his time, he adapted. And we can’t impose our contemporary strategies and standards for survival on Findley’s very complex life. For instance, while the vulnerability he felt as a child and young man certainly influenced his support for animal rights, Grace says, “[Findley] would not link his love of nature and animals to his orientation. There is a wide variety of people who feel the same.” Rather, Findley’s empathy for animals was generational. “There was a time, in my youth,” says Grace, 76, “when people were closer to the natural world. Tiff played in the woods and ravines when he was a boy [near his childhood home in Toronto], and he spent time as a teenager on a farm. His family were dog lovers. He lived in a city but he was not urban the way people are today.” Grace does not make the direct link between Findley’s gayness and his love of nature, instead describing his concern for the future of the planet as an acknowledgment of Western culture’s “nature deficit.” “It was fundamental to Findley,” she says. “He articulated it in his own way, and would not have used contemporary language, but he called it a ‘connection,’ and feared we, as a human population, were losing that connection. Tiff felt that when people lost that connection, they became greedy and destructive. His views were so relevant to how we talk about the environment today and he was very ahead of his time.” While Findley watched the planet go to shit, he found his interior fears mirrored by the world around him. What if everything failed? “I do think fear of failure haunted him right up until the end. It’s heartbreaking,” Grace says. “He believed early on that he was meant to be an artist, and he tried various types of art forms before he settled on writing.” That Findley became an artist of any kind is astounding. His father was God-fearing—with the emphasis on fear—and in Canadian society at the time, an artist was considered something between a thief and a pervert. “He was very ambitious and he felt he had a gift—a God-given gift that, if he failed, he would be failing to honour. The God part is important: He was brought up in a kind of strange hybrid religious context, but the one that came first was Presbyterianism, which is not a forgiving or generous faith.” But Findley was unstoppable. “If you look at how he was treated by Canadian critics over the years, I mean, what a beating he took,” Grace says. “It was devastating to him. It’s a wonder he kept going, but he was driven to write.” Grace, professor emerita at the University of British Columbia, questions my assertion that Findley’s life and career were determined (or over-determined) by homophobia. It’s simply not that easy, she says. “I’ve thought about this a lot. A biographer has to accept that there are things they can’t know. Tiff was very guarded about the topic, but when he did speak out he was eloquent and brave. But the word ‘determined…’ I can just hear Tiff now, grumbling ‘nonsense.’ I won’t speculate, but Bill [Findley’s lover and companion] was critical here, and I think once Bill came along, Tiff decided to plow through the homophobia.” Inevitably, one wonders how Findley would position himself in, or would be positioned by, the current understandings of queer art. “I will say with some confidence that he would not have called himself a queer writer,” Grace says. “Writers and artists, in my experience, resist like hell being put into a box of any kind. But I don’t think Tiff was afraid of being seen as gay, or as a gay writer or writing about homophobia. His novels anatomize war, conflict, racism, injustice, greed, our destruction of the planet—he would be right there with young activists today. “Findley spent his life resisting definition by others.”

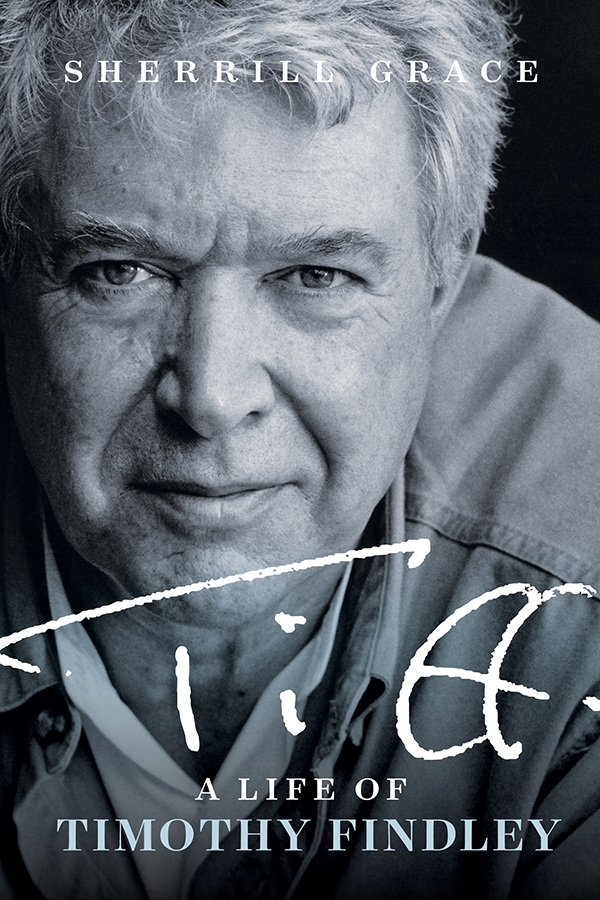

Tiff: A Life of Timothy Findley by Sherrill Grace is published by Wilfred Laurier University Press.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra