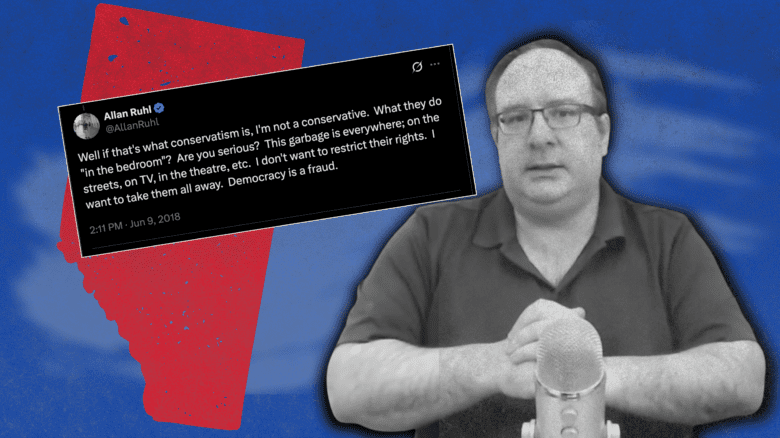

Right now in North America, anti-LGBTQ2S+ forces have waged war against queer and trans folks. Right-wing conservative extremists have tried to discredit our fight for rights, linking pedophilia to the LGBTQ2S+ movement for years. In fact, this March, a Republican candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives compared queer and trans people to pedophiles in a series of tweets. Disinformation like this exists to hurt the LGBTQ2S+ rights movement and is often spread by viral accounts posting inaccurate, harmful messages about queer and trans folks.

But Jane Lytvynenko, a senior reporter at BuzzFeed News, has made it her mission to debunk misinformation on social media feeds on a daily basis. The Toronto-based journalist creates disinformation-debunking Twitter threads and reports at BuzzFeed News about misinformation surrounding current events. Her work is widely recognized on social media, particularly during emergencies or breaking news. Lytvynenko’s work is vital during a time where misinformation and fake news is often taken as fact, especially on social media.

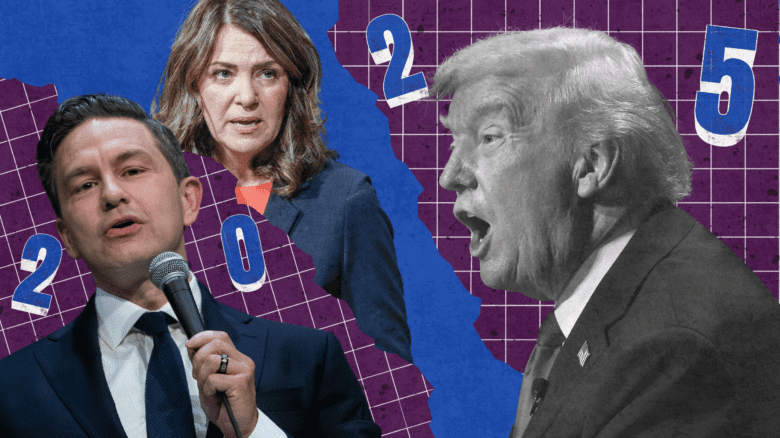

Currently, Lytvynenko is hard at work debunking unverifiable information, conspiracy theories and false information through the American election cycle, particularly regarding President Donald Trump’s COVID-19 diagnosis.

Lytvynenko spoke with Xtra about her work and how disinformation harms LGBTQ2S+ people in North America.

What kinds of disinformation about LGBTQ2S+ people have become mainstream?

Not as much of it has gotten through during the election, but there are two big narratives that we’ve seen pop up over the last few years. One is the anti-trans narrative and using trans people to build online followings and spreading a lot of hateful and inaccurate messages.

“There are things that have been used against queer people for decades, but now they are online and people are creating followings and identities around extremely hateful messages”

The second is this terrible campaign of trying to make it seem like people in the LGBTQ2S+ community approve of pedophilia and view pedophilia as a form of queer sexuality. Those are the two biggest threats and they’re pretty insidious, especially the second one, which plays into a lot of the QAnon pedophilia conspiracy stuff. [QAnon is a far-right conspiracy group that believes the U.S. is run by a Satan-worshipping pedophile trafficking ring, among other schemes.] These have been historic pieces of disinformation. These are the things that have been used against queer people for decades, but now they are online and people are creating followings and identities around these extremely hateful messages.

Have you seen an increase in anti-trans disinformation due to anti-trans comments from celebrities like J.K. Rowling?

I don’t have the numbers in front of me so it’s tricky to say whether or not there has been a rise. But when people with large followings take stances against the queer community, their followers are more likely to feel validated and more likely to be taking those stances. Before J.K. Rowling somehow made being anti-trans one of her pet causes, we’ve also seen some men-focused activism surrounding this narrative take hold. In particular, University of Toronto professor Jordan Peterson became an important figure for men and has touted himself as somebody who can help men improve their lifestyles. He has also built his following on anti-trans comments, so this idea that perpetuating transphobia and anti-trans comments online can get you an audience works both ways. It can both build an audience and it allows a person’s audience to grow and to perpetuate that hate further.

What risks to these messages pose?

I’m afraid of violence. We’ve seen all kinds of disinformation contribute to violence across North America and across the globe. Black trans women are a group that are most frequently targeted in the LGBTQ2S+ community and outside [of the community]. So it’s really scary to think that these anti-trans comments can help justify violence against trans people.

“If a misleading video demonizes a queer person of colour, I would be really worried about people taking that video out of context and taking that video as a call to action”

Part of the danger of disinformation is that it sparks emotions and usually those emotions are negative, like anxiety and fear in people who are watching them. So, if a misleading video demonizes a queer person of colour, I would be really worried about people taking that video out of context and taking that video as a call to action. In the U.S. in particular, there have been insidious rumours that Antifa is coming to local towns, and Antifa has been connected to Black Lives Matter protests by certain disinformation. Black Lives Matter protests have a lot of queer people and people of colour participating in them, and we’ve definitely seen violence perpetuated as part of that rumour. It’s difficult to draw a direct line between one video and one act of violence and one act of hate speech, but when taken as a whole… It is really worrying what kind of effect it would have on people of colour, queer people of colour and queer people.

What is your process when debunking disinformation that is spreading on social media?

There are a few things I do to track online misinformation. One is leaning on online investigation skills such as targeted searches on social media. That includes going into channels and groups that I know are frequent posters of disinformation and making sure that if anything pops up on there I’m aware of it.

I also just ask people what they are seeing. I can’t be in every place online at the same time. I fully understand that there are communities that I am a part of that are targets of disinformation that I’m not seeing. It’s possible that there is disinformation in languages that I don’t speak and disinformation in communities that I’m a part of but am not seeing, so asking people to send me what they see is a key part of making sure that whatever is going around is being knocked down.

How can people spot disinformation and not succumb to the fear?

It is a bit of a tricky question to answer. Overall, disinformation is an issue for platforms and fact-checkers. But at the same time, because we have created online communities for ourselves, we are responsible for making sure that those communities aren’t exposed to false information. You don’t need to be a person who has a lot of followers on social media to take that responsibility seriously.

“We are responsible for making sure that our communities aren’t exposed to false information”

Some quick things I would do before passing on a piece of viral information during a high-stress, breaking news environment: Fact-check that it exists; learn how to do a reverse image search. There are apps and websites that make it easy for you to do that. Check the accounts that are posting. We see a lot of disinformation in comment sections as well. Check to see whether that account is a new account or if it is using a profile picture that is not genuine or if it is posting at a high rate.

A lot of these tips aren’t going to magically prove that a post is clearly a piece of disinformation, but they will help you judge how to engage with a piece of content. They will help you judge whether or not you should pass something onto someone in your online ecosystem. If you still want to pass it on, don’t pass it on publicly, pass it on privately. Make it clear that you don’t know the validity of this information.

Interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra