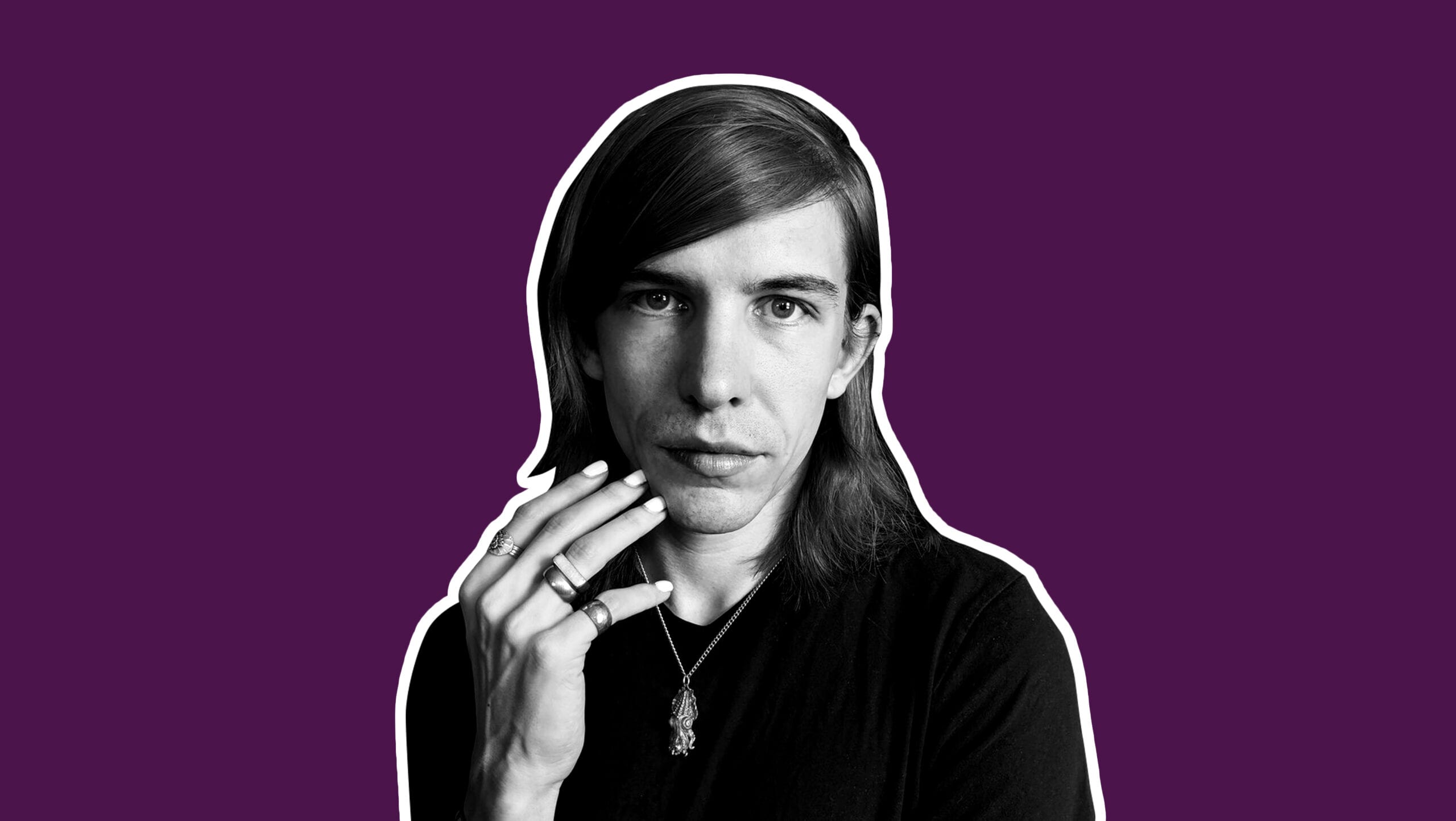

Author John Elizabeth Stintzi wants to complicate the stereotypical narratives of transness that we’re used to. They’d like to see more complex, multifaceted, frustrating or just plain inscrutable trans characters reflected in literature; to do away with the boring, one-dimensional trope of the trans character as perpetual victim. How can we become more comfortable with the conflicting and uncertain nature of identity and reality? If we can see ourselves represented in our confusing ambiguity more often, perhaps we can be more comfortable having identities that aren’t crystal clear.

And that’s what Stintzi’s new novel, Vanishing Monuments, tries to achieve. It follows quickly on the heels of their award-winning debut, Junebat—a collection of poems that explicate the writer’s struggles with their own identity. Vanishing Monuments is a slight departure, a fictional narrative that follows a non-binary photographer, Alani Baum, as they return to their hometown for the first time in decades to visit their estranged mother, who has lost her speech to late-stage dementia. A melancholic and complicated story about grief, memory and identity, the novel is a beautiful and compulsive read, packed with themes and ideas that will resonate with many LGBTQ2 people.

Xtra chatted with Stintzi about Vanishing Monuments, writing trans characters and finding comfort in the uncertain.

While writing Vanishing Monuments, you delved a bit deeper into your own gender. How is the book intertwined with your own identity?

When I started writing the book, I had gently layered the veil of genderqueerness over myself, but I didn’t really understand what that meant at the time. Queerness was a mystery to me because I grew up in the middle of nowhere. I barely knew that gay people were real when I was in high school. I just didn’t envision anyone around me being gay, despite the fact that obviously many were; and I was queer in my own way, but I had no lexicon for what queerness was.

I had an idea of writing a story that would enable me to talk about identity and memory, and the instability of both. So I thought that a gender-fluid character would be a good way to talk about that. When I started to write, I was reading a lot of trans books and learning more about the nuances of gender identity, while also thinking about myself and weeding out my own stereotypes and preconceptions of what non-binary people were like. As I was doing that, I ended up finding that there wasn’t as much difference between me and Alani as I thought there was when I started writing.

There are stereotypes about places that aren’t huge metropolises, that they are very unfriendly places for LGBTQ2 people. Do you refer back to that narrative a bit?

Some of the hopeful things about Vanishing Monuments, which is a dark book in a lot of ways, are the ways in which these people find each other and don’t judge each other and are kind to each other—which may be one of the most unreal parts of the book in some ways.

There’s a certain story of “community” that seems to be purported about queerness. For a lot of people that I know, it’s just these tiny pockets of people and that’s about as good as you get. I think everyone kind of feels like they’re missing something, but that’s probably the most common experience—you’ve got your little family, or your little group of people, and it’s mostly online as well.

Credit: Courtesy Arsenal Pulp Press

The protagonist, Alani, is a very multifaceted character, but they’re also an asshole in a lot of ways. Where does that come from?

I think that characters should be people, and people aren’t necessarily uncomplicated. One of the weirdest responses that I might get to Vanishing Monuments is that people have uncomplicated feelings for Alani, despite the fact that they’re very frustrating and you want to yell at them sometimes. It also depends on the publisher, but there’s some sense among cisgender readers that if there’s a trans character, they have to be suffering and pure. I’m not interested in that, so I don’t know why I would map that onto this project. It wasn’t super conscious in terms of the queerness; that’s just how I view characters.

There have been conversations about the complicated—and, perhaps, unlikeable—trans character as something that doesn’t exist as much as it should in literature. So I’m happy to contribute a small piece to that.

Are there writers who have influenced you in that respect?

The work of Torrey Peters, especially her novella Glamour Boutique. She’s really interested in the unlikable trans character, and speaks to that in a way that resonates with me. Casey Plett’s Little Fish has a main character who definitely isn’t uncomplicated or glamorous or purely positive, but it also isn’t trauma porn. Another book that’s very complicated in terms of its characterization of trans people is Davey Davis’s The Earthquake Room.

Present in Alani’s characterization is the idea that, as trans people, there are parts of our identities that are formulated as reactions to how we’re treated by cisgender society. How would you imagine a queer world to be like outside of the cis-hetero gaze?

There’s this point in the book where Alani speaks to how, as they’ve gotten older, they’ve started to see less stark differences between things. And that’s been my experience with queerness as well—not really understanding and not really seeing the point of polarized identities; feeling more at home in the middle, nowhere-place. Ideally, we will get to a point where we don’t have to feel compelled to be extremely clear-cut to ourselves or to other people, because I feel like that’s mostly a lie anyways. I find it weird that people are so certain about stuff. I think it’s really damaging to a lot of people who are questioning their identities, and who might be in this murky middle ground; the sense of certainty that everyone seems to have also seems to make the process of questioning less valid.

Reading all these trans books and media, you see the characters understanding very early on who they are. And I’d think to myself, “I didn’t have that moment when I was five years old, does that mean that I’m not really trans?” Ideally, we could make a place where people can do whatever they want and express themselves however they want, and where they don’t feel like they have to fight to be considered “real.”

There are a couple of relationships that are very healing for Alani, especially one where they find themselves mentoring a younger queer person.

I think queer mentoring relationships are probably common for many people. Just in terms of being an artist, it’s important to have someone who understands what you’re trying to do and is supportive of you. I just finished a mentorship with the Association of Writers & Writing Programs, where I was a mentor for a trans person working in Minneapolis, and it was really, really healing for me, especially during the pandemic. That’s why I keep trying to get teaching jobs, despite institutions being annoying as hell to work with. I love being able to talk to students and develop relationships where I’m like, I understand what you’re trying to do and I know how to try to help you without forcing my own ideas on to you.

Did you have a mentor?

I wish I had a queer mentor who really understood me and was able to see me in my own way when I was in school. A lot of the healing relationships in this book, especially the queer ones, are ones that I wish I had; they’re fantasies in their own ways.

Can you talk a bit more about people’s varied relationships with art in the book?

I have a complex relationship to art in terms of its cathartic value and its pain value. When I think about how I approached poetry early in my career, there were points where I look back and think: I don’t know that I was doing myself any good writing these really dark and heavy poems. It didn’t necessarily get rid of the feeling—it kind of reaffirmed it. I think that art is not a purely positive expression all of the time, and I tried to capture that idea in the book. Art can be a way to discover yourself, but also a way to concretize the painful things that have happened to you.

With Alani, they conceive of the body as something that’s a nuisance. I believe this is a way of thinking that resonates with a lot of LGBTQ2 people. How can we liberate ourselves from violence when it’s inside our own heads?

I’ve found that the more understanding I’ve had about queerness and the spectrum of queerness has really been calming for me in terms of looking at myself and not hating everything about myself that I wish I could change. I think it helps to be generous to the body and understand that, while it can seem like an obstacle, it’s generally not trying to harm you in doing what it does. As someone who is gender fluid, someone who’s stuck in this weird middle place, sometimes I love my body. Sometimes I like the confusing aspects I can embody, and that excites me in some ways.

I think it helps to try and re-establish your own ideas of what it means to be gendered. Even if the way you are seems to contradict stereotypes of how a person of your gender is supposed to look, with a lot of generosity and care, you can give yourself the freedom to just do what feels fine and not attack yourself for it. But it’s difficult, and oftentimes it doesn’t work. It isn’t always easy.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra