The rainbows started cropping up seven weeks ago, around the same time I started working from home. The first one I spotted was near the railyard, splashed across a living-room window; the second kept company with a love-worn teddy bear by a side-door entrance.

Since then, I’ve discovered dozens of variations on the theme: a triptych of vibrant handprints transferred onto kraft paper, a colourful front yard hopscotch, a flamboyant, multi-storey cut-out of a giraffe with hooves in the dining room and ossicones in the attic.

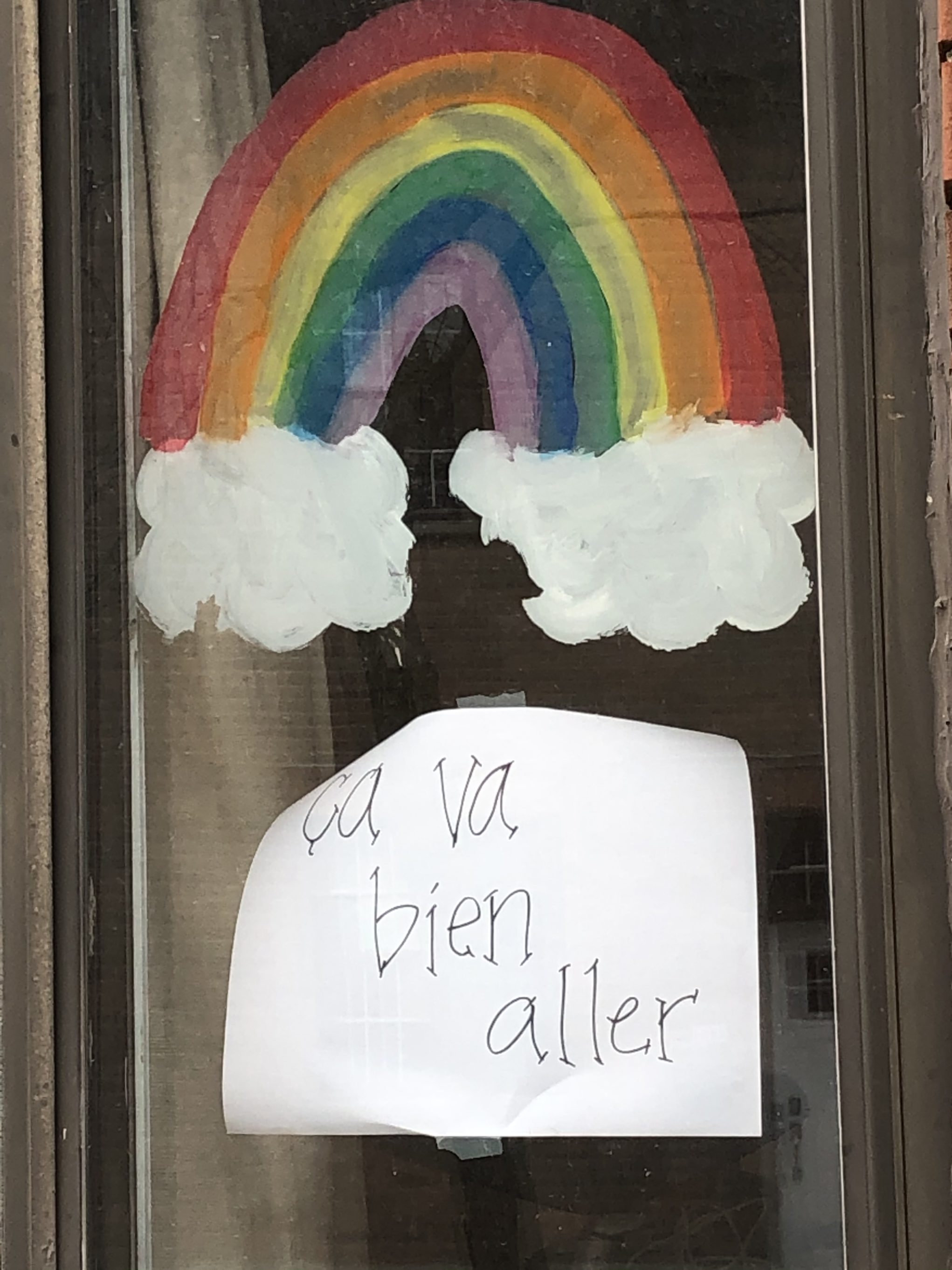

Scattered across my Montreal neighbourhood, these prismatic works of art are accompanied by a Ça va bien aller, sometimes in a jumble of detached letters, other times in slanted cursive or whimsical bubble script. The now-common phrase is translated by English-speaking households as “We got this,” “This too shall pass” or an almost chiding “It will be fine” that makes me laugh when I wander by.

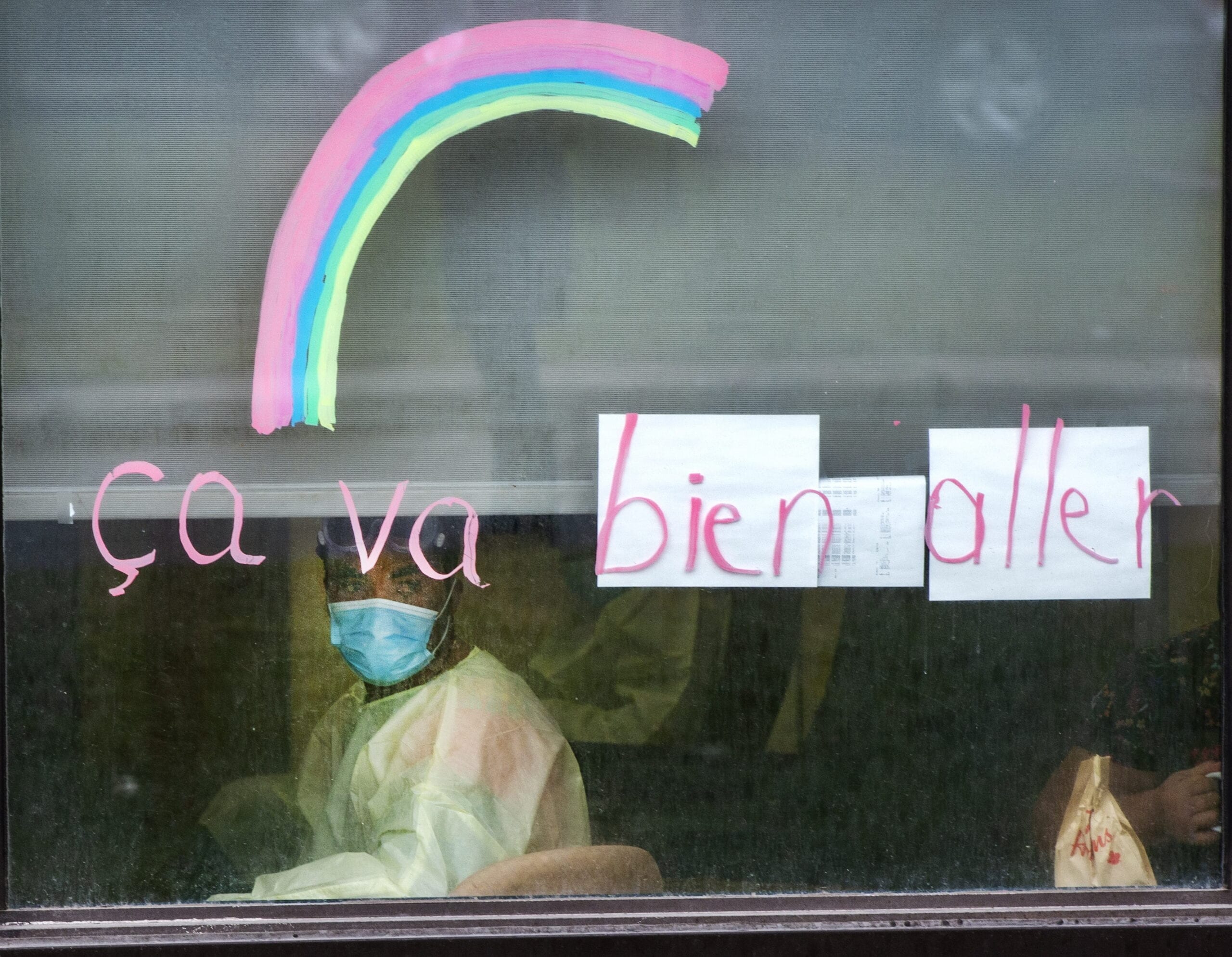

Getting residents across the city and province to display rainbows in their windows wasn’t a queer initiative, though it might look like one. The trend is said to have been started by a group of mothers in Italy—the European country hit hardest by COVID-19 in late February and early March—to help children cope, reassure citizens and foster togetherness. It then travelled to Brooklyn and landed in Montreal homes thanks to an Italian-born early childhood educator who wanted to spread hope and comfort as the novel coronavirus crisis worsened. Major landmarks—from the Jacques Cartier and Champlain bridges to the Olympic Stadium and the Museum of Fine Arts—have followed suit, lighting up their facades in bright colours to become beacons.

Traditionally, the area I live in is more likely to have buildings tagged with anarchist graffiti than it is to showcase rainbows every 20 metres. And yet, during this confinement that has stretched from days into weeks, more and more childish chalk drawings have joined the “ACAB” and “Support Wet’suwet’en” messages in the alleyways. And the more I look at them, the less dissonant these tucked-away pairings become.

The Jacques Cartier bridge in the Old Port of Montreal, is lit up in rainbow colours during the COVID-19 pandemic. Credit: The Canadian Press/Graham Hughes

Rainbows are about resistance and resilience.

I understand they don’t mean the same thing to everyone. For the first 14 years of my life, I associated them with the wallpaper in the bedroom I shared with my sisters, Pot of Gold chocolates and God’s covenant with all living creatures (Noah and his ark were my jam). It’s only after I had my first crushes on girls that I saw rainbows differently. I began looking for them glued to bookstore windows and car bumpers, or adorning the necks or earlobes or canvas bags of other teens. If I found one, it meant I’d found someone at least a little bit like me.

But these days, every time I pass our front window I am greeted by an “Everything will be okay” rainbow secured to a sill by the same across-the-way neighbour whose go-to expletive is a homophobic slur. Across the pond in the U.K., some have even appropriated the rainbow flag as a symbol of solidarity with frontline workers. The rainbow as I cherish it has been drained of its queer connotation.

Am I right to be upset by this? My neighbour has no way of knowing the kid I used to be grew into a young lesbian who grabbed onto rainbows like buoys. She likely doesn’t know about Gilbert Baker or Harvey Milk or their mission to create a symbol of pride—as imperfect as it may be by today’s standards—for a community that had so often been reviled. A community that until then had lacked a widespread emblem that said, “Come in, you are welcome, you are celebrated.” In the decades since, many schools, shops, restaurants and religious spaces have come to use that very emblem to demarcate queer-positive zones. Safe spaces, for us.

Gabriella Cucinelli, the early childhood educator, is right: The rainbow is a symbol of hope and comfort. But it’s also a symbol of strength and a reminder of inequalities and it does, to a great degree, belong to queers. During this fraught period, I want to honour that (and give my neighbour a bit of a history lesson). But ultimately, I’m happy to share. Let us find what sense of belonging and common purpose we can in those coloured arches.

After almost two months, the rainbows have begun to fray—the kraft paper is curling up at the edges, the chalk drawings have been muted by spring showers. As Quebec companies have glommed onto the message and turned it into messaging, it’s easy to be cynical: Rainbows are being used to sell cleaning products. And they aren’t tangibly helping the most marginalized among us, from people experiencing homelessness to the people working and living in Montreal’s besieged long-term care residences.

A rainbow poster in a window in Montreal. Credit: Courtesy Stéphanie Verge

And yet. My wife and I don’t have children, so our friend’s nine-year-old took it upon herself to mail us Ça va bien aller artwork for our front door. It’s two-sided: one rainbow faces out for passersby and one rainbow faces in for us. If I said that her drawing and its postscript (“We love you and we’re thinking of you”) doesn’t make me feel a tiny bit better, I’d be lying.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra