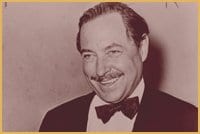

America’s greatest playwright spent a portion of his final years in Vancouver.

That Tennessee Williams would end up here (he was appointed Distinguished Writer-in-Residence at the University of British Columbia in 1981) gives his story the poetic tidiness myth-makers —and a public increasingly hostile to complexity —yearn for: a bona fide artistic icon in pathetic, irreversible decline, coasting on the laurels of a once-glorious career in what was then a cultural backwater.

More concretely, Williams was a bitter, fall-down drunk, and a lascivious connoisseur of rentboys to boot. In short, an old queen who had become a parody of his own most tragic (female) characters, a far cry from the bashful poet who ignited the American stage with The Glass Menagerie 35 years earlier.

With two recent Arts Club Theatre productions that ran (virtually) concurrently —a revival of Menagerie and the world premiere of Canadian playwright Daniel MacIvor’s His Greatness, which tells the story of Williams’ stay in Vancouver —local audiences were afforded the rare opportunity of seeing both faces of the southern bard (virtually) side by side.

What unites the two plays is not just that they are about Tennessee Williams (Menagerie being by all accounts heavily autobiographical) but also that they pit, as does the entire Williams oeuvre, truth against illusion —albeit in entirely distinct ways.

While the Arts Club is to be commended for programming this salutary diptych, artistically the two productions were only partially successful.

“I am the opposite of a stage magician,” says Tom, the narrator (and author’s surrogate) in Menagerie. “He gives you illusion which has the appearance of truth, and I give you truth in the pleasant disguise of illusion.”

Spoken like a true homosexual in pre-Stonewall America, these words are descriptive not just of the mellifluous, visually rich new style —termed “poetic realism” by critics —that Williams almost single-handedly brought to the American stage but also of the particular milieu homosexuals had to navigate: a world of codes and ellipses, disguises and masks.

How does this manifest itself in Williams’ plays?

In Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, ostensibly heterosexual ex-football player Brick is tormented by the suicide of his buddy, Skipper, who had confessed his love for him before he died. When his wife and father attempt to drag the truth out of him, he spews, “Why can’t exceptional friendship… between two men be respected as something clean and decent without being thought of as fairies… .”

Because virtually all of Brick’s speeches on the matter conveniently trail off into ellipses, the truth remains forever elusive.

In A Streetcar Named Desire, Williams’ magnum opus, Blanche is an aging belle, cultured and sensitive, obsessed with youth and beauty, haunted by her gay husband’s suicide. She is simultaneously repulsed by and drawn to her brother-in-law Stanley, perhaps dramatic literature’s most memorable embodiment of animalistic masculinity. (As portrayed by Marlon Brando —he was our culture’s first “hunk” —the modern male sex symbol was a decidedly gay innovation for which we have Williams to thank.)

Williams’ own assertion, “I am Blanche DuBois,” only reinforces the widely held reading of the character as a gay man in drag. In the words of famed American theatre director Joseph Papp, “Williams’ writing has the complexity —the dual sexuality —Shakespeare shows so often in his characters.”

For the essence of Williams’ art was complexity, in terms of both abstract design —the abundant, meaningful imagery and rich allusiveness that give his plays the aureole of myth —and, as Papp said, character.

And the complexity of Williams’ work is inseparable from the social context in which he operated: repression forced him to side with the lonely, the alienated, the ostracized, the dispossessed, and to transform them into theatrical characters that throbbed with life-like complexity.

It was inadequate complexity that was the problem with both Arts Club shows.

With The Glass Menagerie, there was, among other things, a failure to exteriorize the play’s gay subtext; with His Greatness, a failure to move beyond legend or reveal anything fresh or new about its subject.

The exquisite Menagerie, based closely on Williams’ own family story, is about meddlesome, Depression-era-mother Amanda’s attempts to better the lives of her two children: her shy, crippled daughter Laura and her temperamental, artistic son Tom.

Explicitly hinting at Tom’s queerness would have greatly added to the poignancy and pain of the family drama; instead, actor Robert Moloney, under the direction of James Fagan Tait, gave the character a pedestrian reading and with little sense of his inner life.

Therefore, when his justifiably suspicious mother asks him where he goes late at night, his response, “I go to the movies” carried none of the code-like suggestiveness that it should have. And when Tom talks about and to his sister’s gentleman caller, whom he deems “astonishing,” it was without a trace of anything other than friendly disinterest.

Cherise Clarke looked right for Laura but as so much of the character’s essence is found outside the spoken words rather than in them, she could have been more responsive and made greater use of meaningful gestures.

On balance, the show’s most successful performance belonged to Craig Erickson, who was funny and charismatic as the good-natured all-American who captures Laura’s heart before breaking it.

But the show was dominated by Gabrielle Rose’s Amanda.

Overall, tackling a role as nuanced and fully-fleshed as any in world drama, Rose was impressive despite some missed targets. Too often actors have gone the easy route with it and gone for pure laughs, and while Rose intelligently avoided this, she failed to completely project the loss and desperation underneath the ridiculousness.

And when there was a clear opportunity for pathos —as when Amanda reminisces about the summer she caught malaria fever —Rose played it much too stolidly.

She redeemed herself at the end.

When the Gentleman Caller’s visit goes awry and Tom leaves the house for the last time, Amanda’s heartbreak and fury shot across the proscenium, and the effect was devastating.

It was the script, not the production, that hampered Menagerie’s companion piece, His Greatness, which was inspired by Williams’ aforementioned stay in Vancouver shortly before his death.

Playwright MacIvor sets the play in a hotel room where three unnamed men —The Playwright (Williams), in town for a production of his play; The Assistant (The Playwright’s lover/caretaker); and The Young Man (a rentboy) —converge and, over a period of two days, speak of art, dreams, faded hope and lost glory.

The performances, under Linda Moore’s direction, were uniformly excellent.

David Marr was appropriately prim as the taken-for-granted assistant, and Charles Christien Gallant brought both sexiness and naïveté to the role of the rentboy. As The Playwright, Allan Gray was well-nigh magnificent, imbuing the narcissistic scribe with palpable warmth, charisma and heartbreak. That he looked eerily like Williams only added to the wonder of his performance.

The by-now widely circulated legend of Williams being little more than a boy-chasing drunk while in Vancouver is, like most legends, a gross distortion of the truth; according to those who actually worked with him, he was thoroughly pleasant and professional —painstakingly, unerringly devoted to his craft.

But, apart from the beautiful monologues that bookend the play, His Greatness never shows you what made Williams the artist tick, opting instead to go the expected route and perpetuate the familiar myths.

For what matters, ultimately, is the writing.

The knock against Williams today is that his work was pre-Stonewall; that in our more accepting age, his depictions of people tortured by and for queerness are passé. Such statements are obviously from those who have never set foot outside an urban centre, let alone a non-Western country; in the majority of the world, being queer is still taboo, even criminal.

No one is advocating a return to pre-Stonewall repressiveness but there may be something in the Nietzschean idea that conflict makes one creative. Certainly, no post-Stonewall gay playwright (no, not even Tony Kushner) has come close to emulating the example Williams set for creating works that throb with the totality of life and for giving the outcast so memorable and complex a voice.

It is an example young gay playwrights should return to.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra