This story is part of “Still Fighting,” a series exploring the past 50 years of LGBTQ2 activism in Canada.

My involvement in queer activism started back in 1971, when I signed the “We Demand” document. It was a 13-page brief with 10 points calling on the government to change laws and policies that affected gays and lesbians, and I was the only woman to sign it. At that point, I was 20 and was already out to my parents and friends. (I identified as a lesbian at the time. These days I refer to myself as queer or bisexual.)

“We Demand” felt important because we really had no rights back then. Much of the hoopla surrounding the “decriminalization of homosexuality” in 1969 is overblown. Then–prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s famous line is “the state has no place in the bedrooms of the nation.” But the government was forcing us back into our bedrooms. You could still be fired for being gay. You could still be refused a job or an apartment. Decriminalization didn’t give us human rights.

That year was also the first Pride in Toronto. The atmosphere was joyful—a real “we’re here, we’re queer” feel. It wasn’t that different than Pride today, except instead of a million people, we were about 100. That, and nobody wanted to support us back then. There were no governments, no corporations on our side.

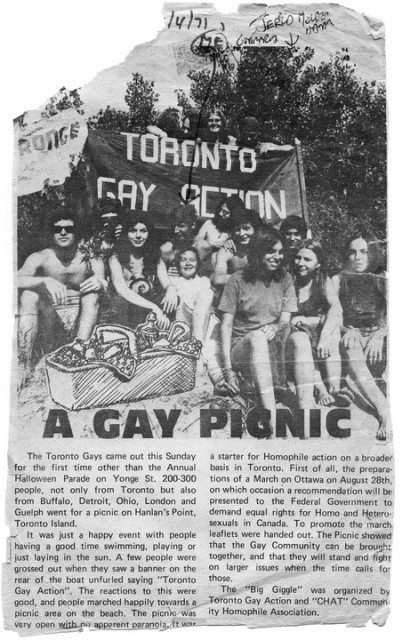

That day, we marched down to Hanlan’s Point, on the Toronto Islands, for a picnic. There are a couple of famous pictures from that day, and I’m in one of them with my girlfriend at the time. I still have a framed copy in my office. We look very cute.

The first Toronto gay picnic at Hanlan's Point. Credit: Courtesy Guerilla magazine

After the first Pride, I stayed involved in the LGBTQ+ movement. The Toronto bathhouse raids in the 1980s were mostly about the boys, but I, like many queer women, showed up to march to Queen’s Park alongside them.

In 1988, I joined a United Church congregation in Richmond Hill, Ont. I moved around to a few different churches after that and eventually became part of the ministry at Toronto’s Emmanuel-Howard Park United. That’s where, in 2001, I performed one of the first same-sex marriages registered in Canada. Keep in mind, same-sex marriage wasn’t legalized in Canada until 2005. But two queer women of colour, Paula Barrero and Blanca Mejias, approached us asking to be married, and our congregation didn’t see any reason why they shouldn’t be. They were in love.

Back then, straight couples getting married didn’t necessarily need a marriage licence from City Hall. You could read the banns—a public announcement of an impending marriage—in church. I did, and didn’t mention whether the parties were male or female—I just referred to them as the bride and groom. The Ontario registrar mistook the name Paula to be a man’s name, and certified the marriage. We were ecstatic, but once the media learned what had happened and reported on it, all hell broke loose. What followed was an absolutely wild few years.

The Ontario government sent a letter to the United Church asking them to take away my licence. Although they were the biggest protestant denomination in Canada to ordain openly gay and lesbian folks, they stayed silent. They didn’t strip me of my licence, but they refused to support me. Thankfully, my congregation stuck together. I got Toronto lawyer Doug Elliott to work with me, and he sent a cease-and-desist letter to the registrar’s office. The press was covering us favourably at that point, and the government backed off for long enough for the case to make it to Ontario’s Supreme Court, which ultimately allowed the couple to stay married. I did eventually get a written apology from Queen’s Park just as I was leaving politics—but it took about two decades.

A few years after I officiated that marriage, Peggy Nash, who was a Toronto MP at the time, asked me to lunch. I accepted the invitation and during our meeting, she said, “Would you consider running provincially with the NDP?” I was shocked. I’d always thought of myself as a social justice activist, not a politician. I took a few months to think it over, but eventually agreed, and won a seat in 2006. Between then and 2018, as a member of provincial parliament in Ontario, I passed more LGBTQ bills than anyone in Canadian history.

My first major piece of LGBTQ legislation was Bill 33, Toby’s Act, which became law in 2012. While sexual orientation was in the Ontario Human Rights Code, gender identity and gender expression were not. We wanted trans folks to have official legal protection from discrimination.

I named the bill in memory of a friend. Toby was a trans woman who had been part of our church. She was an incredible musician and everyone adored her. When she died from an overdose, it was a huge blow to the community. I knew that her name should be on a piece of legislation, and Bill 33 seemed like a good opportunity for that.

Next was banning conversion therapy in Ontario. During my stint as the province’s first LGBTQ critic, I met with a trans advocacy group in Sudbury, Ont., called TG Innerselves. When I asked them what they wanted from the Ontario government, they told me to work to ban conversion therapy. I was shocked to learn how pervasive the practice was—not just among right-wing religious groups, but counsellors and psychiatrists as well. Just before Pride in 2012, I introduced a private member’s bill that delisted the practice for adults and banned it outright for minors. I went to then–premier Kathleen Wynne and said, “Do you want us all carrying signs saying this supposedly queer-positive government is not going to ban conversion therapy?” Her party helped us get the bill passed in two weeks—it was a miracle.

The last big piece was Cy and Ruby’s Act, which was passed as Bill 28 in 2016. We were approached by two women, both lawyers, who were married and had two children together. Before the act passed, even if one queer parent donated sperm or got pregnant, their same-sex spouse would not automatically be considered the child’s second parent. They wanted to change that.

I introduced another private member’s bill to allow married same-sex couples to automatically become legal parents of their children, and after a complicated legal battle, we got that pushed through as well. When the bill was voted in, nearly half of the Conservative caucus was absent. Nonetheless, we had the support of people from their party, and the Liberals as well. That wasn’t unprecedented for me. During my political career, I tabled the most bills that had the support of all three parties.

I decided to leave politics at the end of 2017. I had accomplished a lot, but it was time for me to go. Being a politician comes with the power—and I used that power. But I’m a drooling old socialist and I never liked having a boss. I’d been chastised by my party a few times by then. When I spoke to the media about conversion therapy, when I complained that the Ontario NDP ran a terrible campaign in 2014, I got my ears slapped back. I wanted to go back to running my own show. Besides, being an activist is way more fun. Don’t get me wrong, I got more private member’s bills passed in Ontario’s history than anyone. That’s beyond fun. But it takes a toll. Each one was an uphill fight.

With activism, you have more freedom, no hierarchy to answer to, or expediency issues to deal with.

I landed as a minister at Trinity St. Paul’s. It was a perfect match—the church has been inclusive for decades. We just buried a queer man who had been a member of the congregation with his same-sex partner for 40 years. That’s how far back the church goes in being LGBTQ-affirming.

These days, we’re attracting more millennials. Younger queer folks especially need a place like that they can run to—somewhere that will affirm them and fight for them. Our congregation wants to be that community—we’re directly advocating for LGBTQ rights, environmental rights and migrant rights.

We can’t get too comfortable with the rights we’ve gained. Things are going to get scary—everything we’ve worked for is under threat right now. Bigoted people who had shut their mouths are opening them again, and speaking all sorts of garbage with impunity. Just look at the group of anti-LGBTQ+ Christians who tried to march though Toronto’s gay village in September. We have to be proactive, not just reactive, and elevate queer voices, trans voices, people of colour’s voices.

We also need to be internationally minded. Lots of countries that we vacation in or do business in—throughout the Caribbean, for example—are criminalizing or killing queer people. We need to put pressure on politicians, but also put pressure on our banks, the places we shop. Until we’re all safe, nobody’s really safe.

Still, blending faith and activism gives me hope. At its best, the church is a loving, accepting community. And that’s what we are here.

As told to Megan Jones

This story is part of “Still Fighting,” a series exploring the past 50 years of LGBTQ2 activism in Canada.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra