Kevin Hart was faced with a rather simple decision when past anti-gay tweets resurfaced following the announcement that he would host the 2019 Oscars: Apologize or else the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences would rescind the offer. Hart decided to step down rather than say sorry.

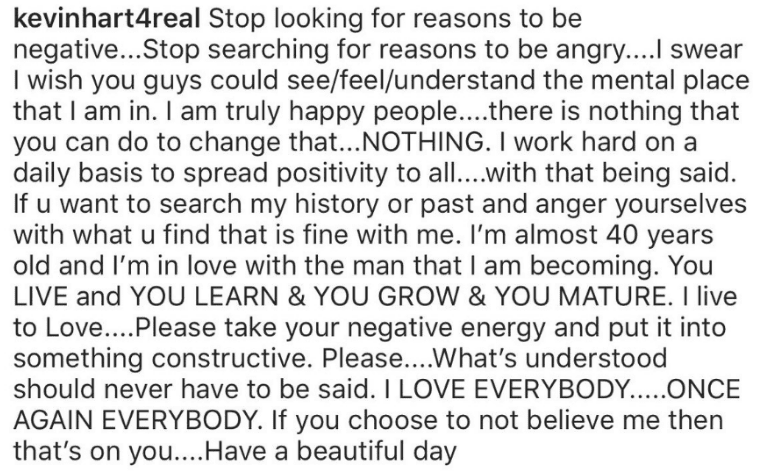

There was no remorse, no simple, authentic apology. Instead, Hart took to Instagram on Thursday night to tell people to “stop looking for reasons to be negative,” that he was “almost 40 years old” — a whole grown-ass man — and he was maturing and learning from his past mistakes. But what Hart has forgotten about being a man, about being an adult, is that to mature means admitting when you’re wrong.

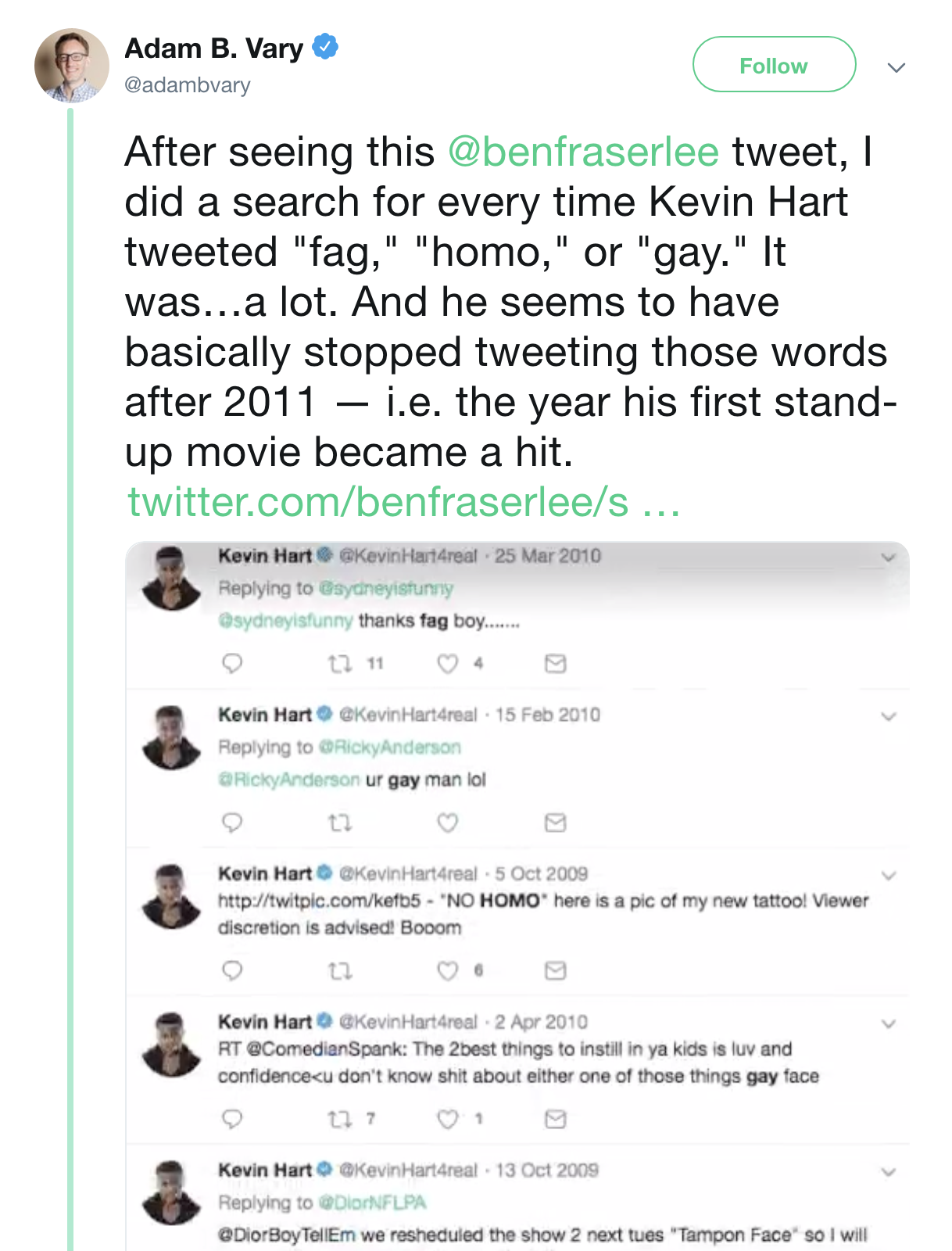

Social media users found endless tweets from Hart using the words “gay,” “homo” and “fag” and even calling someone a “gay bill board for AIDS [sic]” from several years ago, which ended sometime around 2011, when his career took off as a blockbuster star.

It’s not uncommon for comedians to push the boundaries of jokes — to move into offensive territory for laughs, to try out jokes on social media, to take off-limits topics and push the boundaries. But Hart’s anti-gay rants aren’t funny; there’s no punchline or a takeaway. And whether these tweets signify that Hart is, in fact, homophobic (and as actor Billy Eichner said on Twitter, “What bothers me about these is you can tell its not just a joke-there’s real truth, anger & fear behind these”), it still reeks of toxic Black masculinity.

Credit: kevinhart4real/Instagram

Toxic masculinity are harmful patterns of behaviour associated with most negative stereotypes about what it means to be “a real man”: being unemotional, tough, sexually aggressive, violent, misogynistic and homophobic. Toxic Black masculinity is a hypermasculine form of maleness framed through racial ideologies, a concept with origins stemming from the emasculation of Black men at the hands of white slave masters. It demands that Black men must act like big, tough men, or risk being emasculated by society.

Black masculinity is embedded in the socialization process of children: Don’t cry. Fight to settle an argument. Don’t show emotion. Dress a certain way. Don’t touch other men. Don’t let anyone — society, your peers, your woman — dare tell you that you are less than a man.

This performance and policing of masculinity is so toxic that “softer” traits are considered gay or effeminate, and so strongly enforced that even showing affection or giving compliments to another man must be followed by a “no homo.” From childhood, toxic masculinity denies Black men freedom to determine and express their own sexuality, giving them little chance to understand that there are many ways to be a man.

Which is all the more concerning when you take one of Hart’s 2011 tweets about breaking a dollhouse over his son’s head if he caught him playing with it: “Yo if my son comes home & try’s 2 play with my daughters doll house I’m going 2 break it over his head & say n my voice ‘stop that’s gay.’” He deleted this sometime on Wednesday or Thursday. This was not a one-time comment: during a skit from Hart’s 2010 comedy special Seriously Funny, he said having a gay son is one of his biggest fear as a straight man, and he’d correct homosexual behaviour by responding with “Stop, that’s gay.”

Credit: adambvery/Twitter

Hart’s comments reflect his own insecurities about his Black masculinity: in an industry that values the stereotypically tall, dark and handsome Black stars like Idris Elba, Michael B Jordan, Morris Chestnut and Winston Duke, Hart has taken on characters that play into his small stature, such as the annoying brother-in-law of Ice Cube in Ride Along, and the fast-talking accountant alongside Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson in Central Intelligence. He also talked to Oprah about being “beyond confident” in his height, yet admitted that it was a big insecurity as a child. It makes sense that in a film career where his roles are limited to the funny small guy, that he must find other ways to perform masculinity, and find other targets to help deflect from his own inadequacies.

There is most definitely an audience that Hart appeals to with his anti-gay comments. Toxic Black masculinity and homophobia often go hand-in-hand, though there are plenty of Hollywood stars and creators breaking the cycle through expansive and inclusive models of Black masculinity: Frank Ocean, Dev Hynes, Jaden Smith, Kidd Kenn, iLoveMakonnen, and Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight, to name a few.

But seeing as Hart has had different followings throughout his successful career from his time as a comedian to a big-name star, a sincere apology would go a long way in recruiting a new fan base — a queer fan base — that would clip the circle of toxic Black masculinity that is not only ever-present in society, but enabled by the stars we follow and adore.

Nowadays, most celebrities who’ve done wrong atone, whether out of sincerity or for damage control. But hypermasculinity — toxic masculinity — never admits when it’s wrong. If Hart thinks in 2018 that his resurfaced tweets from seven years back wouldn’t require an apology, then the joke is on him.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra