The trouble with Surrealism is that it’s no longer surreal. Sigmund Freud’s theories have now blended into the tide of mainstream pop culture, and a tiger jumping out of another tiger’s mouth ain’t nothing you can’t see in any multiplex theatre in any given summer. It’s not just that Surrealism’s source material has lost cultural currency, its images have long since stopped being challenging. That’s just how it goes: What was once an avant-garde revolution now graces the pages of calendars and mousepads.

The artistic confrontation with the psyche that Salvador Dali, Giorgio de Chirico, Jean Arp and others envisioned has made the pilgrimage from avant-garde to acceptable to commercialized to kitsch.

This inevitability is something that the curators of Surreal Things, the Art Gallery of Ontario’s summer show (via the UK’s Victoria and Albert Museum), wisely attempt to account for. The show traces, over the course of the first half of the 20th century, how, through the vagaries of taste and fashion, Surrealism made the ginger step from art movement to design aesthetic, and then exploded into mass popularity.

The show is relatively small, but still manages to give a whirlwind tour of Surrealist practice in four rooms, touching on all the major practitioners. It introduces its theme with a bang, a vast recreation of de Chirico’s set and costume design for Les Ballets Russe, which touched off a major scandal within Surrealist circles for abandoning the purity of art for the sullied commercialism of the theatre.

For me the unpacking of this infighting was one of the major delights of the show. As I said, it’s easy to forget that, prior to two World Wars, or Dali hamming it up on the Dick Cavett show, or Rene Magritte being day-calendar fodder, Surrealism was a utopian aesthetic philosophy that aimed to plumb the depths of the human psyche.

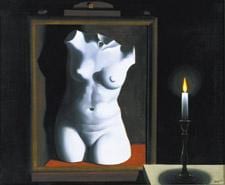

Among the Surrealist paintings assembled (decent works by de Chirico, Dali and Joan Miró among others), Magritte is a painter who never fails to impress me, and who, for my money, comes the closest to articulating the psychological shock at the heart of Surrealism. Dali is too extravagant and showman-like, and any conceptual urgency gets lost in all the florid theatricality. It’s the plainness of Magritte’s paintings, the spare, matter-of-fact way he represents his impossible juxtapositions — a cannon in a fireplace, a stone boulder filling up a room — that channels the uncanniness of dream logic.

The most excitement in the show is to be had with the objects; for one thing, they haven’t suffered from overexposure. In their translation of Surrealism into design the designers seem to latch on to the idea of trompe l’oeil. Dali’s jewellery for instance, spends all of its extravagance mimicking anything and everything: an enormous brooch shaped like a tumescent tropical flower, a choker that looks like a fountain with little spurts of diamonds at regular intervals that shoot out and splash forming a necklace. Or Elsa Schiaparelli’s dresses: a “torn” gown, made of fabric printed with strips of skin torn away to reveal magenta blood (a trick she builds on in the matching cowl, where stray bits of fabric are sewn on to look as if they’ve been peeled off); a bolero jacket that looks like a comforter cover; and a skeleton dress, a black form-fitting number with fully articulated ribs, collar bones and one long, gnarly spine that travels down the back.

Ultimately, however, these things are less surreal than just fabulous. That skeleton dress doesn’t shock me with my own mortality; I want to wear it. And this is where Surreal Things makes its point: Paintings and sculptures can afford conceptual purity (especially in the early 20th century) but design is at the service of a client. The broader the design market, the more palatable the aesthetic has to become.

As a final underscore to this, the last room consists of Surrealist furniture design: modular, kidney-shaped tables and sofas, Miró-designed wallpaper swatches. Taken all together, it looks like any boutique furniture store in this city. By the time I turned the corner into the gift shop, hawking Surrealist perfumes, magnets, umbrellas and figurines, I couldn’t tell if that was expert curation, profound irony or an unwitting commentary. Or maybe it was a combination of all three.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra