Growing up, I never liked having my picture taken.

When my relatives pointed their cameras at me, I’d try to duck out of the frame. I never understood why they wanted to keep me captive for as long as that image survived. The idea that someone could photograph me as though they owned a piece of me, without asking me how I wanted to appear or be remembered — I wasn’t comfortable with any of that.

My parents gave me my first camera when I moved to Toronto, a handheld digital device with a single button to document my adventures at university and my new life in Canada. I went berserk trying to take photos of as many things as possible, clicking that one button as though it were a video game controller as I tried to get pictures of my freshly-decorated university dormitory from every possible vantage point.

Pressing that one button did nothing to improve my photography skills. As classes began and homework piled up, my stream of photos slowed to a trickle. It wasn’t until I reached my second year and upgraded my phone to a smartphone with a front-facing camera that I started to take pictures again. But this time, I practised on myself.

When I started taking selfies with my smartphone, I became both the owner and the subject of photos, controlling who got to see them. I would take hundreds of selfies from different angles, turning around in slow circles to find the best-lit spot. Looking through all the photos and happening upon the one I wanted to share with the world was incredibly satisfying.

As a queer, trans person of colour, total control over my own image was everything I had always wanted. And photography became the way I could experiment with my gender expression and live out ideal visions of how I wanted to look.

I started modelling just under 18 months ago. I didn’t want to make money or become famous — I wanted to make up for the years I refused to have my picture taken.

Iris Robin. Credit: Courtesy Poynter Photography

Initially, I worked with my photographer friends. They practised their photography skills on me while I clumsily tried to figure out how to pose and express myself. Starting with friends was a good move: they were people who already knew me and liked me, and who already knew that I’m queer and trans. I didn’t have to explain anything to them and they never asked me to. We just focused on our respective creative growth and had fun while doing it.

I quickly realized that I had it easy when it was just me and my friends. When I decided to branch out and find opportunities outside of my social circle, I discovered many model castings demand a “Caucasian” person or someone with “natural blonde hair” — and since I’m neither, these opportunities excluded me.

While I did find “open ethnicity” castings, that still meant that white people would be considered along with people of colour. It’s a reminder that the industry upholds white models as the most desirable and frequently shafts models of colour.

Even when I found photographers who wanted to shoot me, I encountered too many who simply didn’t know how to edit my photos. I’ve received numerous images where my skin appears lighter or where the image is so oversaturated I look orange.

When cisgender models of colour are already struggling to find opportunities, there’s little space for discussions about the limitations imposed on transgender and gender non-conforming models — much less if those transgender and gender non-conforming models are also of colour.

Because the fashion industry is built around binaries, with clothing divided into “men’s” and “women’s” categories, I’m always read as a woman and misgendered. The attires themselves don’t bother me; I’m happy to wear any kind of clothes as long as they fit me. But if they’re to be advertised as women’s clothing and I’m walking on what is described as an all-women runway, I don’t feel entirely comfortable knowing that everyone watching will be under the impression that I’m a woman.

In March, I walked in a fashion show with the themes of multiculturalism and diversity. I let the organizers know that I didn’t fall within the two gender categories that they established for the show before attending my casting call, and they said that was fine. The organizers knew what a nonbinary person was, which was far more knowledge than I’d ever expect from the majority of cisgender people I meet on a daily basis.

When I received an email telling me that they liked my audition and I’d been chosen for the show, I was excited and optimistic. I could finally do a fashion show without worrying about being misgendered.

The event involved a rehearsal and a promotional photoshoot that took place a week before the show itself. In preparation for the shoot, the organizers sent out an email with the dress code. To my dismay, they had used gender to determine what each model would wear, with separate dress codes for men and women. I emailed them back and asked them to clarify: which dress code should I follow?

They replied promptly and said that I should choose whichever option I felt most comfortable with. I didn’t know how to tell them that I wasn’t comfortable with either.

I chose the “male” dress code for the event because I wanted a more masculine vibe for the show itself — and also because it was cold outside and the women were instructed to wear shorts whereas the men could wear long pants. As I waited with the men, I watched the women huddle together for warmth and winced sympathetically as periodic gusts of wind made them squeal.

The fact that I had a choice in the dress code didn’t make me feel more accepted or understood; I was anxious the whole time because I was waiting for someone to question where I had chosen to stand, to say “shouldn’t you be over there with the women?” or “why are you with the men?”

Luckily, that didn’t happen. But the whole time, I felt like it could have.

Even when creative directors choose me for jobs because of my genderqueer self-expression instead of treating me like an afterthought, the experience isn’t necessarily better. Once, I was chosen for a project because of my androgynous appearance and aesthetic, and had the chance to discuss the shoot beforehand. I was to do one masculine and one feminine look, then have both edited onto the same page for a clear Victor/Victoria concept. I told the creative director that I was genderqueer and that I was excited about this project because it was an opportunity for me to express two aspects of my gender authentically and artistically.

Part of the deal was that the clothes I wore would be custom made, so I sent in my measurements. But when the day of the shoot rolled around, I found that my clothes were neither custom-made nor did they fit me at all. Each one of the four outfits I tried on was too big. The heels offered by the wardrobe stylist didn’t fit me either.

“It’s hard because you’re so petite,” the wardrobe stylist told me.

I was livid. The size of my body wasn’t the problem. It was that evident that she hadn’t received my measurements or had simply chosen to ignore them.

I shouldn’t have been disappointed that a white cisgender wardrobe stylist was ill-equipped to find clothes for a genderqueer model of colour. But I was. It was her job.

Credit: Courtesy Darryl Pezzack Photography

I didn’t want to have trouble finding work later because I complained and someone on the team perceived me as ‘difficult’ for raising my concerns. The team had chosen me for this project because of my look. What my colleagues had failed to realize was that for me, this wasn’t just a “look” — it was my identity, something I live out every day.

The team should have taken advantage of my knowledge and experience about gender fluidity to strengthen the project’s effectiveness and impact. The miscommunication — whatever it was — was the fault of the production team. But the industry standard measurements, whiteness, cisness were likely a large part of why the stylist was unprepared to find clothes for me. She might not have ever worked with anyone who had a body like mine.

Shorter, Asian, queer and trans bodies are less common in the modelling world both due to a comparative lack of opportunities and the industry’s framing of such bodies as less desirable. Incidents like these may discourage those like me from pursuing a career as a model. And that’s to say nothing of the immense challenges that darker-skinned queer and trans models face.

Diversity is a hot-button topic and a trendy look for the fashion industry right now. At this year’s New York Fashion Week, Marco Marco’s Collection Seven featured a runway comprised entirely of transgender models.

I am skeptical of efforts that treat trans models as representatives for all trans people when cisgender models are never expected to ‘represent’ anyone other than themselves and the designer they’re walking for. Transgender models should be on the runway, not as representatives for the trans community, but because the industry has adapted and welcomed us such that we can work to the best of our abilities. We should be here because we’re everywhere else. We deserve to have our needs met and our identities respected, and to have the same opportunities as white, cisgender, straight models.

I’ve begun to stand up for myself. When I do, I’m standing up for other models like me, and the industry becomes that little bit easier for all of us to navigate.

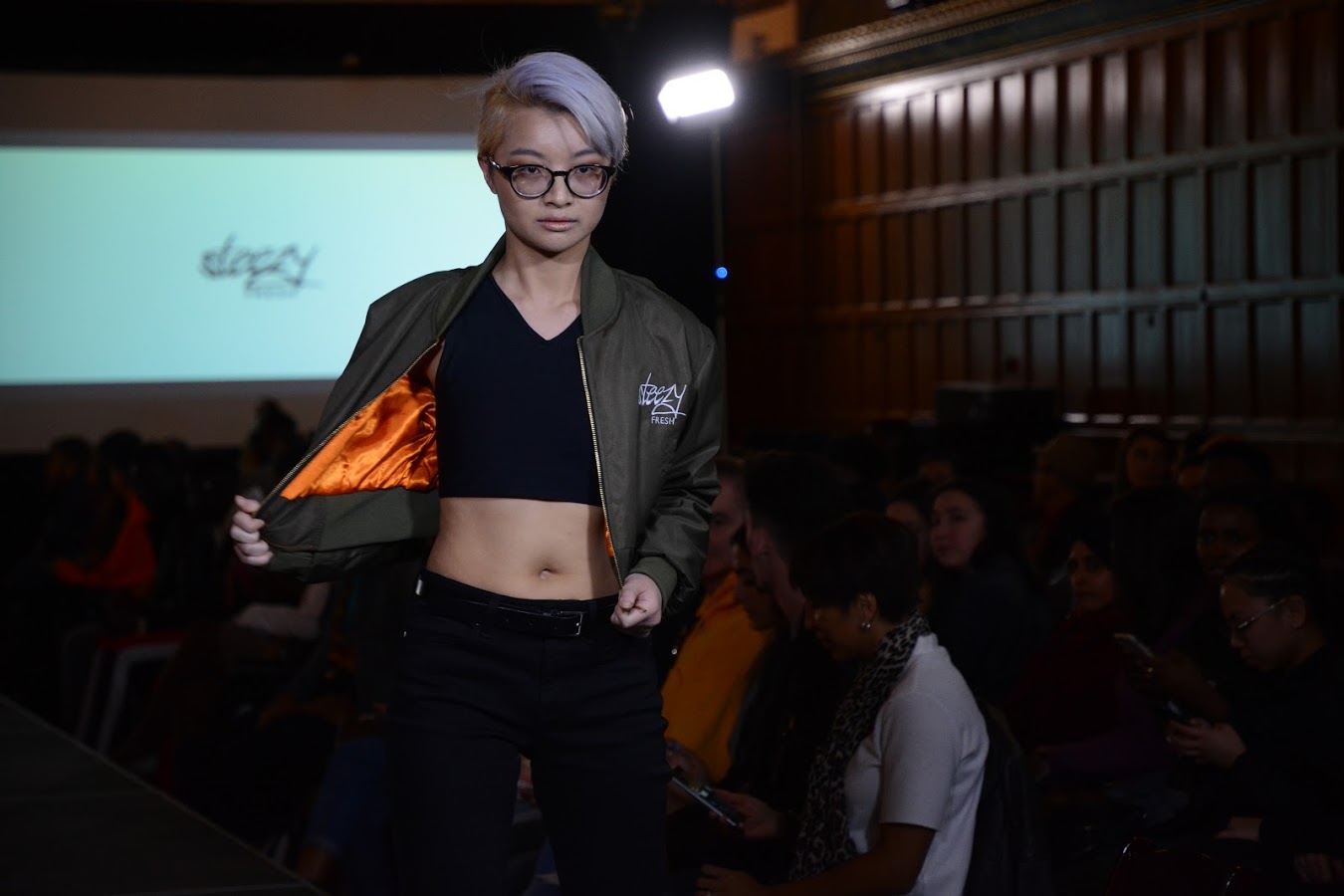

More recently, I’ve been asserting myself at work and I’ve noticed an improvement. I’m now a model with agency experience and commercial work on their resume. Despite facing an organizing team that didn’t understand me, I spoke to the designer of that same show with the gendered dress code. I walked in that show while visibly wearing my binder, which is what I was most comfortable wearing, and it looked incredible with the jacket I was modelling.

At a shoot I did a couple of months ago, I corrected a photographer on my pronouns, and she went on to correct other members of her team when they used the wrong ones. She was completely at ease with using they/them pronouns and I felt so relieved that I didn’t have to explain myself to her because she was already educated. I was comfortable for the duration of the shoot. I felt free to be myself and I think that my work improved significantly because of her thoughtfulness.

I was grateful then, but even more so when the people I work with take the time to read the information that I’ve provided and explore my online public presence before we start the job. I did a fashion show this April where the designer quietly approached me to say that she saw I used they/them pronouns on my Instagram profile and wanted to double-check that she was using my pronouns correctly. It meant a lot to me because she showed that she cared about my wellbeing and my personhood, and took steps on her own to ensure she got it right.

But treating me with such respect should be the norm, not an exception. The fact that I can recall these isolated times when I’ve been lucky enough to work with people who treat me with compassion and dignity reveals the problem: that standards built around cisgender white people still govern the fashion world.

Credit: Courtesy Steven Lee

While dealing with a lack of understanding about my gender, I’ve also had to confront the prevailing idea that there can only be so many marginalized people in one place. Although I have met other models of colour and other queer and trans models, there are often only a handful of models of colour on a project, with one of each ethnicity because representing the diversity within whole races and cultures would be “too much.” And that’s because people want their work to be diverse — but not too diverse.

Despite this, I know we queer and trans models of colour are so much more than a monolith. The fashion world has been slow to catch on, but we’re getting there.

We aren’t tokens to check off the “representation” boxes with. We are the future of fashion.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra