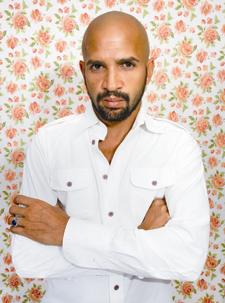

THE RIGHT TO RECKON WITH THE OFFENSIVE. 'It's my own experience, you can't argue with somebody's experience,' says Berend McKenzie. 'You can empathize or not, but you can't say, "No, that's not true," or "No, that can't be."' Credit: Sarah Race

“Nigger,” says Berend McKenzie and unfurls his right arm away from his body, palm slightly open.

“Fag,” he says in the same matter-of-fact tone, this time uncoiling his left arm.

“I know. They make me uncomfortable. They make me angry. Welcome to my world.”

“As a child,” he explains, “I realized I had [these] two things working against me, and both would determine the course I took in life.”

With that quietly explosive prologue, the slightly built McKenzie-as-Buddy relentlessly unleashes his lifelong collision with the historical power that the words nigger and fag have been infused.

Nggrfg is a one-man, hour-long performance of four vignettes — Liner; Oh, Brother; Father, by the way; and Tassles. They mark pivotal periods in McKenzie’s life when those two words, either separately or together, have elicited deep shame, grief and terror of the private and public kind.

He weaves the tale non-linearly, morphing seamlessly and assertively into the different personae that make up his life’s trajectory. At first, he’s a 16-year-old mouse of a teen desperately trying to be anything but his obviously gay self, as he vies for the affection of the edgy, mohawk-sporting girlfriend of his high school dreams. With her on his arm, he thinks, his street cred would skyrocket. His predatory schoolmates won’t call him fag anymore.

Fast forward, and he’s 40, a frustrated actor battling entertainment industry stereotypes — and the grating ignorance of his own agent — about the roles black men can play and how they should play them.

“You may not be black enough for many of the roles out there,” the agent whines, disparagingly adding that his client needs to be “a little more ghetto” in his self-presentation.

Then the agent’s parting shot: “Do you have to be so… gay?”

That Buddy does not at all embody the smooth-talking, black-man-as- gangsta-rapper mold is painfully and humorously conveyed during a hapless stab at an audition in which his rhythm-less take on a bad-ass hip-hop artist, Little Bro’, leaves a roomful of “real” black men rolling in the aisles.

“I was the whitest guy there,” Buddy observes.

Flashback: and Buddy is a vulnerable 30- year-old trying to connect with his physically and emotionally distant black, biological father who is pleased that his son landed a supporting film role opposite Halle Berry, balks upon hearing it’s the role of a gay man, finally becoming painfully silent when his son reveals he is actually gay himself.

Finally there’s Tassles, and for McKenzie, the “emotional high point” of the journey. But this final chapter is the real beginning of Buddy’s conflictive, life-altering relationship with “nigger,” which he first encounters as a seven-year-old watching a television adaptation of Roots with his adopted, white father. And then again on the school playground, where Buddy, ecstatically skipping with a pink, tassled rope incurs the torment of Nelson, the school bully who aims and fires both nigger and fag at him.

“I was called a nigger and a fag together, as a kid and as an adult,” McKenzie, the playwright says, but it wasn’t until he began conceptualizing nggrfg that he delved inside himself to sort through his feelings about the words — particularly nigger.

The catalyst for all that analysis arose from a series of media moments McKenzie witnesed: one, a standup routine in which Seinfeld sitcom star Michael Richards (Kramer) called his black audience niggers, another in which conservative American commentator Anne Coulter labels one-time vice-presidential candidate John Edwards a faggot.

Television talking heads and news anchors had a field day with the two events, McKenzie remembers.

“The bubble heads would say, ‘Should we ban the n-word?’ or ‘Should we ban the word faggot?’ And then the anchors would say, ‘What do you think? Should we ban the n-word or should we ban the word faggot?’

“They wouldn’t say nigger, but they would say faggot over and over and over,” McKenzie remembers. “In a nine-minute segment, everybody was tossing it back and forth 25 times.”

For McKenzie, the answer was a no-brainer back then.

“I was watching that and going, ‘Yeah, we should ban the words. We should get rid of them, they’re bad, they’re bad.’”

It was only after a longer, more reflective conversation with friend and nggrfg co-producer, Darrin Hagen, that McKenzie began reassessing the stridency of his stand and his knee-jerk instinct to jump on a censorship bandwagon.

“If we ban those words, and if we’re not allowed to talk about them or to use them, where does that leave me?” McKenzie remembers asking himself. However inflammatory the words nigger and fag were, they were an intrinsic part of his life’s journey.

“In that conversation,” McKenzie remembers, “Darrin said, ‘That’s got to be the name of your next piece!’”

But McKenzie also recalls Hagen advising him to make sure he knew how he felt about the words before writing the show.

“I knew how I felt about the word fag, because I use it all the time and I use it with my friends and I use it to describe other people,” McKenzie explains. Gays have “taken it and dressed it up and made it our own and shown it to the world.”

“Faggot is something that I didn’t like of course when I first came out,” McKenzie acknowledges. “At one time people hated the word queer. Now queer is a way that we use to describe the community as a whole, [and] fag seemed to take that progression.

Not so much when nigger is the word elephant in the room, he observes.

“If you’re sitting around a group of black people, you do hear, ‘Hey, nigga, what up?’” McKenzie concedes. Still, he contends, black people have not been able to take the word and “flip it” into something truly and universally positive and celebratory. “There’s too much evidence, there’s too much record about what happened when the slaves were brought to the Americas.”

“The word nigger has always been a really difficult one to get out of my mouth,” he adds. “Nigger brings on a sense of fear and dread and anxiety and a lump in my throat and apology.”

Even as he began promoting nggrfg or simply telling people about what he’d been working on, McKenzie says he had to steel his courage to be able to utter its name. “When I first started saying the title for people, I would always preface it with, ‘I don’t mean this to offend you but the title is…’ or ‘Please don’t take offence…’ ”

He says both the provocative title and its intentionally vowel-less spelling have made for some curious interactions.

“I’d have people that don’t know how to say it, some people that don’t want to say it, some people go, ‘How do I pronounce your show?’

I’m like, ‘It’s what you think it is. You either call it nf, or you say it, however you feel comfortable. The show about the black gay guy,” he says with a laugh. “Or don’t say it at all.”

White guilt regarding the show’s name is huge, he notes. It’s usually white people who say, ‘Oh no, you can’t. No, no, no.’

“I had quite a few black people going, ‘I don’t know, brother, I don’t know, man.’” McKenzie adds.

But his intention is not to incite or anger people, he says, but to initiate more open dialogue about words – and people’s experiences with their power – that really cannot be erased.

“It takes me explaining that these words were used as weapons against me,” therefore giving him the right to talk about them and turning them into something good, that allows people to get it, he says.

He has performed Tassles, the first offspring of what is now nggrfg at Edmonton’s Loud and Queer Festival, as a stand-alone piece. The response was overwhelming, he recalls, with audience members lining up to tell him about their own experiences with the hateful use of language.

Almost a year after completing nggrfg, McKenzie is calmly philosophical and more self-assured about the words — even grateful for them.

Somewhere in the process of writing the four stories, McKenzie says, he decided that the words themselves weren’t bad.

“There’s nothing wrong about language. Language is awesome. It’s what people do with language that hurts and incites panic and fear and anger and resentment and hatred. It’s the people behind the language.

“I respect these words, I’m humbled by these words, and by what people have lived through so that I could come up with a piece like this,” he maintains. “Because I am black and because I am gay, it’s allowed me the opportunity to write a play like this.”

McKenzie says if he were white and straight, “there’d be no way.”

“It would be held up as racist and homophobic,” he says. “But because it’s my own experience, you can’t argue with somebody’s experience. You can empathize or not,” he allows, “but you can’t say, ‘No, that’s not true,’ or ‘No, that can’t be.’

Neither is the goal to tell the audience to feel a certain way.

“I needed to be able to tell myself, that even with these two words, that I was enough and I am enough. This is just my story.” McKenzie asserts.

“I think that’s what has given me the courage to do it.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra