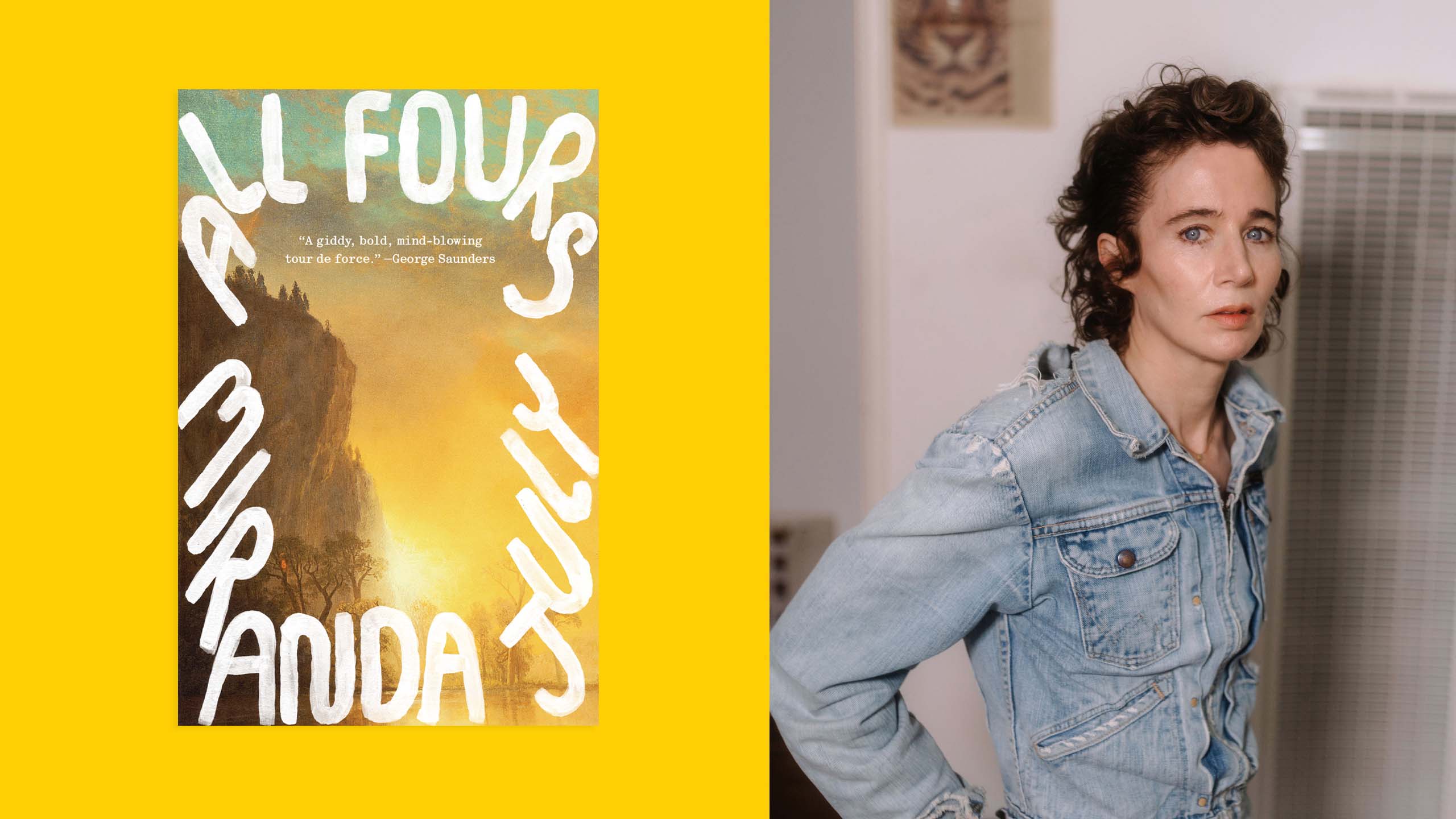

There might not be a mind quite like Miranda July’s in contemporary culture. Regardless of the medium she’s working in—film, art, literature, performance art—she always creates something utterly unexpected. Consuming a piece of her art often comes with more questions than answers, but in a welcoming way. Her take on the world around us has a distinct viewpoint—she looks at garden-variety topics through a kaleidoscope that refracts completely different meanings than the status quo. Her films Me and You and Everyone We Know, The Future and Kajillionaire all explore human connection and relationships, as does her first novel, The First Bad Man, through a lens only July could render.

Her latest novel, All Fours, is no exception. The book follows a 45-year-old semi-famous artist going through a midlife crisis. She’s preparing to take a road trip from Los Angeles to New York—leaving her husband and child at home. It’s the first time she’ll be leaving them both for an extended period of time and she’s stressed by the prospect. But her itinerary changes only 30 minutes into her trip, when she unexpectedly decides to exit off the highway into the town of Monrovia, checks into a motel and sets herself on an entirely different journey. She finds herself smitten with a local younger man, Davey, and they embark on an untraditional relationship. While her husband and son believe that she’s still driving, the only person who knows what’s going on with her is her best friend, Jordi. Through our unnamed narrator’s journey, July, now 50, examines the preconceived notions we have about women aging, their desires and needs, and motherhood. July looks at the places where one can rediscover oneself—and how those places are often ones we’d never expect.

Here, July speaks to Xtra about the novel, what midlife crises look like for women and why we all need to queer the marital institution.

All Fours is so incredible. I was just constantly delighted and shocked by it. What was your initial inspiration?

I started it when I was 45 and I was overwhelmed with the sense that there was suddenly this scarcity of information I was used to from being a young woman—when there was just tons of involvement in your body and all the aspirational ways you could be. I could see that stopping, and more than that, I could feel the perspective shift. Now, when I look forward, it’s death and old age and that’s such a huge perspective shift.

I thought: where’s the conversation about [women aging]? The book was the book I wanted and reflected the conversation that I was having with all my friends and with other women I met.

It feels like we rarely see representations of women having midlife crises. You see that with men with their sports cars and younger women. But you really show the narrator going through her own midlife crisis as a way to find herself again.

During a midlife crisis, you enter this territory and you think, “I’m being silly. I’m a mess, I’m a wreck.” And it’s like, no, we are meant to transform and we are shamed out of it. We’re always transforming. There’s this sense that every time the narrator and her best friend Jordi meet, they are different people—they’re also realizing, over the course of a lifetime, that there are going to be these major shifts in their lives. So that’s built in for us as a midlife crisis. It’s also a crisis that happens in puberty. I think it’s part of it probably in death too.

This character clearly needs and wants to create space for herself—you see that in her abandoning her road trip to New York and then spending a bunch of money sprucing up her hotel room in Monrovia. Making space is a way to find herself. But she also seemingly finds herself through a relationship with a new lover, Davey. He seems to see something in her that she forgot—why did you want to explore her crisis through that emotional affair?

I think if you have a part of yourself that’s starving, it’s usually in your blind spot and you’re concerned with other things. Then when that part’s seen, even by some sort of random, marginal figure, that starving part of yourself leaps out that is suddenly unleashed and not willing to go back in the box. That was very easy to relate to feeling. I wanted this character to not be stoic.

What role does sex play in that type of discovery?

I do think the first sex a person has with someone new after having sex with one person for a long time involves a reorientation—a sort of coming out feeling, like, “Oh, wait, who was I all along?”

You explore desire in All Fours in so many different ways: from the narrator’s decadent attraction to a pink bedspread she buys for her hotel room, her relationship with Davey, her sexual fantasies, her search for finding herself again. Why was it important to look at it from many viewpoints?

It’s only ever useful writing about sex for it to be a widening process, widening telling of sex. It’s insane how narrow [the definition of sex] is and how much pain that causes. I tried in all different ways to untie those knots and yes, to have some things feel erotic, but then also to have her not have desire in some places or not be sure if she was going to be able to. People sometimes feel bad about feeling that way. It’s like, well, why aren’t you hungry right now? The desire to have [sex] is the hottest thing of all.

A very unexpected exploration of desire in the book is a scene where Davey inserts a tampon in her. They can’t be physical in a more traditional way—because they don’t want to have a full-fledged affair—so this is the way they explore that attraction. I’ve never read anything like it.

Sometimes I’m reading or watching something and I think something is about to happen and it’s my own insane idea of what’s next. I think that happened in a book or movie [I was reading or watching]. I was like, “Oh, he’s going to put the tampon in.” After I get over my disappointment [that it didn’t happen], I’m like, “That’s mine.” It was a different way for me to think about a period. No one had ever offered to put in my tampon. For me, that suddenly seemed like a great loss.

There’s a line that really stood out to me in the book where the narrator says about the people in her life, “You’ve all missed the point of me.” I love that line so much, and I feel like that really kind of gets into the way that women are as they get older. We’re supposed to almost disappear.

In that moment, it’s funny. It doesn’t mean I’m not fucking serious as hell. She’s being loony, but she, in her own conception of herself, is dead serious and wants to be understood and seen fundamentally. Certainly as you get older, you’re faced with a sort of disregard almost. In my experience, it’s not like we want to be regarded in the same ways as we were in youth. We have outgrown those and now we have a new understanding. There’s nothing that exists for us, and so we have to make it out of our own minds and relationships.

I love the way that the relationships between women are shown both with the narrator’s deep friendships and also her sexual relationships with women, when her marriage opens up. She says she just wants to be seen, and throughout a lot of the book, when she’s most seen it’s by other women.

There was this question of how much weight [should her relationships with women be given]. Given she was in this straight relationship, relationships with women, with friends, are “supposed” to be secondary. The bet she begins to place or the way she starts to shift her weight is like, what if this is actually more? What if I put all my weight here? Could I build a home weighted in this direction? There are a lot of little moments that aren’t so little. They could be tossed away, but I think just trying to figure out, is this enough? Is this substantial? Because nothing in the world will tell her that this is sturdy.

The narrator starts out in a fairly traditional marriage before she goes on her meandering journey to self-discovery. By the end of the book, she’s in a much different arrangement. Why did you want to dismantle the marital institution in that way?

I’m just staggered that on the whole, we’re still doing marriage the same way. Even taking something like poly relationships out of it, it’s like just marriage. There are a whole bunch of different ways that marriage could look. Anything other than the norm is still all seen as pretty radical. I was having conversations with other people and it almost immediately became seen as a kink if relationships were in any way different than traditional. I was interested in presenting that less like, “Oh, aren’t we so radical?” I wanted to look at different relationships in practical terms—with all the fears too. There’s a sort of surrealness when you’ve been attached to a typical structure—it may not have worked, but it felt real because obviously it’s there in the culture.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra