IT'S OFFICIAL. Livingstone, centre, joins two couples signing the partnerships register he created, at a ceremony in 2001. Credit: (David Walberg)

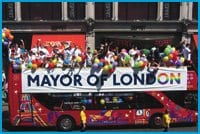

One could be forgiven for thinking that Ken Livingstone owns London’s Pride celebrations. As promotional ads for the festival blanket the city, the mayor’s logo — simply, the words Mayor Of London in clear, bold capital letters — shouts from every Pride billboard and banner, identifying his office as the event’s major sponsor.

The man himself is nearly as ubiquitous. He launches Pride week in late June with a characteristically rousing speech outside of London’s new city hall. On Pride day itself, Livingstone leads the parade as it snakes through the city before flowing into Trafalgar Square, where he speaks again to an enthusiastic crowd spanning as far as the eye can see.

The parade has just ended when I meet Livingstone in the lounge at the Trafalgar Hotel, situated across the street from Canada House in a corner of the square. It’s a roasting hot day and the mayor is chatting and chuckling over a glass of wine.

I’m surprised to see him imbibe before an interview, given his tortured relationship with the press. In many instances, he’s a refreshingly mouthy mayor. Yet he faced suspension from his office this year after comparing a badgering journalist to a concentration camp guard.

To no one’s surprise, the scandal had a gay twist — the tussle occured as the mayor left a ceremony marking 20 years since Chris Smith, the UK’s first openly gay MP, came out. The mayor accused the newspaper in question and its reporter, who turned out to be Jewish, of harassing guests at a predominantly gay and lesbian event. Last month he won his challenge of the suspension.

A longtime gay rights activist who isn’t even gay, Livingstone is close enough to the community that any history of his career would be broadly streaked with gay highlights — major accomplishments as well as the odd gaffe.

***

At Pride, Livingstone is in his glory, pleased as punch with the gay rights successes that have occurred during his term as mayor, many of them attributed to his own Labour party.

“In Britain since Tony Blair was elected, homophobia has become effectively illegal,” he tells me. “You can have a partnership in which you get the legal rights that married people have… we have lesbians and gay men in the government, and so it’s been a huge sea change.”

A worldly man, he’s also brimming with confidence about the prospect of gay rights progress around the globe.

“I mean, on this march today, we’ve got people from Venezuela, and you can’t have a more macho culture than Latin America,” he says. “Yet Hugo Chavez, the president of Venezuela, has written in his constitution rules against homophobia, has declared Caracas a homophobia-free zone.

“And if you can make those changes in Latin America, there’s nowhere in the world where eventually we can’t change.”

Livingstone expects to help make those changes, and does not limit his efforts to his London jurisdiction. Earlier this year, he spoke out against both the mayor of Moscow and the president of Poland. Both leaders attempted to ban Pride marches and later condoned the violence that met gay activists who defied the bans.

After Moscow’s Pride ended in bloodshed, Livingstone announced, “To see open fascists and Nazis parading in Moscow, and assaulting lesbian and gay people, is to trample on the memory of all those who fought against Nazism and particularly the 27-million Soviet citizens who died in the fight against fascism.”

Livingstone shares with me his recipe for social harmony, whether in diverse London or in places where gay rights are unknown. “You have to actually say to religious fundamentalists, whether they’re Christian, Jewish or Muslim, what they’re doing and saying is unacceptable,” he says unequivocally.

But then he channels his inner cultural relativist. “In Russia, Stalinism froze attitudes on race and gender and orientation, and they’re now catching up. In a few years’ time, the pink ruble will have its effect and the mayor of Moscow or his successors will recognize what having a gay Pride march actually brings to us, and it brings money.

“We shouldn’t get too arrogant now,” he warns. “Forty years ago — I mean, it was actually only 40 years ago that [homosexuality] stopped being illegal in this country, and even when it stopped being illegal, it still was a real career downer. It’s really only in the last 10 years that being lesbian or gay in the commercial or government sectors has not damaged your career.

“So we’re not in a position to be too supercilious about all this. We’ve had hundreds of years of persecution ourselves. The rest of the world will catch up.”

***

Not that London is one big rose garden. Closer to home, Livingstone singles out education as a priority. The mayor has joined forces with gay activist group Stonewall on a project called Education For All.

“One area in London where there’s still homophobia is our schools,” he says. “Stonewall and the mayor’s office are circulating every school in London with a DVD for teachers, how to deal with homophobia in your school.

“Because the most vulnerable time in the life of a lesbian or gay man is when they realize they are. They’re 12 or 13 or 14, they don’t know anyone in the world is like them, and they can’t talk to their parents, and their teachers — they’re frightened to talk to them — and so we want to have an open debate in our schools.”

During our chat, I’m intrigued by Livingstone’s ambiguous presence. He appears both boyish and ancient, rugged and fey, princely and poor. He is at once the friendly cherub, the mischievous imp and the wise crone. One minute he mouths off like a scrappy street lad, the next he pronounces with the air of a regal dowager.

“If you go into our schools,” he continues, “and you say a racist remark other kids will criticize it. If you say a sexist remark, certainly at least the girls will criticize it. But you can be homophobic and no one complains.

“This is the legacy of Mrs Thatcher who made it illegal for teachers to talk about homosexuality. And so this is the single most important thing left in London to do.”

I ask whether this will be mandatory curriculum, and he clarifies an aspect of local government control. “Oh no. I don’t run the schools. They’re run by the 32 London boroughs,” he explains. “But some schools will take this and they’ll run with it. And others will, well, the head teacher will say ‘filthy perverts,’ and so it will end. And it’s just a slow, inch-by-inch progression.”

Inch by inch, perhaps. But for Livingstone, it must feel as though he has come full circle. Twenty years ago, it was a similar push for gay-positive education that became a catalyst for a dramatic show of rage and force from Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government.

***

Ken Livingstone led London once before, in what must seem like another life, or perhaps another country. In 1981, he became leader of the Greater London Council (GLC), where he was first elected as a member in 1973. The GLC was a progressive oasis in Thatcher-era Britain, and thus became a thorn in the Iron Lady’s side.

In his first year as leader, Livingstone gave the first “gay grant” to the London Gay Switchboard, and in 1985, another GLC grant helped start the London Lesbian And Gay Centre. During this time, Livingstone was dubbed Red Ken by the tabloid press. GLC members, among other progressives, became known as “the loony left.”

In 1986, the lesbian and gay unit of London’s Haringey borough wrote to schools asking them to promote “positive images” of homosexuality. That’s when the shit hit the fan. The backlash galvanized opponents of progressive local government just as the Conservatives made good on their plan to abolish the GLC entirely, which they accomplished that same year with relative ease.

The next year the Tories introduced legislation to prevent the “promotion of homosexuality” by local councils. The notorious Section 28, as the legislation came to be labelled, was passed into law in 1988. The law, which was not overturned until 2003, was a major setback to gay rights in Britain, particularly in schools. The Stonewall group formed in 1989, largely in response to the law.

Given this history, I ask Livingstone if he expects a similar response to the Education For All campaign.

“No,” he says. “No, and the big difference with 20 years ago is, well, I suppose the media has played a big role…. I suppose there are parts of Britain, remoter areas, where it’s still very backward.

“In the great cities, in London and Manchester, we’ve had all these studies showing economies are more dynamic where you’ve got an open lesbian and gay community. The cultural dynamism in that community, its effervessence, impacts on the economic process.

“In UBS, which is one of the major international banks, in London, their chief executives actively support their lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender group of workers because they know, if the culture in UBS is offensive to their gay and lesbian staff, they’re going to lose talented people with real skills that create profit.”

This is the second time in a week I’ve heard the mayor praise a bank — at the Pride launch, he had singled out the support of investment firm Morgan Stanley. He has already told me that commerce will be key to ending homophobia in Russia, and I’m sensing a theme. I ask him whether one ought to find such statements strange, coming from a man once known as Red Ken.

“No, no. Business has changed,” he asserts. “Thirty years ago big business was totally reactionary in Britain, signed up to the Reagan/Thatcher agenda. Opposed to public spending. Racist, homophobic, all that.

“When the Thatcher/Reagan agenda didn’t deliver long-term benefits — short-term benefits, but not long-term — and now that the European and American economies are under such pressure from India and China and the emerging economies, we can’t afford to write off 10 percent of our population and their potential, any more than we can write off the 50 percent that’s female.”

***

Livingstone’s resurrection in London was a slap in the face, not just to Margaret Thatcher, but also to Tony Blair. After Thatcher destroyed the GLC in 1986, the city went without a central administrative body until the Greater London Authority (GLA) was created in 2000.

In the intervening years, Livingstone served as a Labour MP. But he lost his bid to become the Labour candidate for London’s first mayoral election in 2000, with Blair reportedly saying Livingstone would mean “disaster” for the city. Livingstone defied the party, ran as an independent — and won. Famously, his victory speech began thus, “As I was saying before I was so rudely interrupted 14 years ago….”

Livingstone was expelled from Labour for his chutzpah, but was readmitted (with Blair conceding he was wrong) in time for the 2004 mayoral election, in which he won a second term.

In 2001, just a year into his first term as mayor, Livingstone set up the London Partnerships Register, making the GLA the first public body in the country to make gay relationships the equals of straight ones. At the time, Livingstone told the BBC, “Although our register is only a small step on the road to equality, I would like it to act as a trigger for real change.”

Indeed, by 2004, the Blair government had passed the Civil Partnerships Act, legalizing same-sex unions nationwide. But local councils have notable autonomy in the UK, and several — including Bromley in South London — tried to prevent gay couples from using council premises for their ceremonies. Livingstone displayed his newfound influence among even politcal opponents when he pressured the Conservative-controlled Bromley council, resulting in the ban’s reversal.

Livingstone was credited with facili-tating another gay about-face last year. Conservative-controlled Westminster council banned rainbow flags from flying outside businesses in the borough’s Soho neighbourhood. Revealing the puritanical thread that hems so much recent urban planning, councillors described their antiseptic scouring of Soho as “removing visual clutter.” But councillors reversed their decision after Livingstone called them, among other things, “Neanderthals.”

By the time it was over, he had the borough’s cabinet member for planning declaring: “The flying of rainbow flags is an important tradition in this part of Soho.”

***

Livingstone wears a casual T-shirt as he addresses the homo throngs in Trafalgar Square, but it feels as though he’s wrapped in a victory mantle. The crowd adores him — a sea of smiling faces beams in his direction. People cheer, hoot and holler. They wave their arms and pump their fists in assent to his words.

The crowd’s fealty endures even as the mayor’s speech goes on and on, incorporating a lengthy, puzzling detour in praise of the Hugo Chavez regime in Venezuela.

Livingstone has recently been vilified in the British press for hosting Chavez in London, and perhaps he sees an opportunity to vindicate himself in this hijacking of Pride. If so, the hostages seem happy with their lot. They splash playfully in the fountains and wave huge, gay versions of the Union Jack — the blue replaced by shocking pink.

The mayor is credited with offering Trafalgar Square to Pride. The festival had long sought what the English call a free rally to punctuate the parade, and the mayor came through with the city’s most treasured public space.

Livingstone has spruced up the square with an expensive and controversial project that uses hawks to scare away the pigeons, which had become so numerous they had turfed out the people and turned the square, literally, into a shithole. Now, the city invites major festivals like Pride to bask in the newly renovated space.

Even the former colonies get in on the fun, although they continue to suffer imperial slights: the gays trump Canadians in London, and so Canada Day was celebrated a day early in the square this year, so that on July 1, the homos could have the run of the place.

London has flourished during Livingstone’s tenure as mayor, and even unexpected voices credit him for the city’s renaissance. London First, a group representing 300 of the city’s major businesses, recently voiced their approval of the mayor’s controversial congestion charge, which uses tolls to reduce traffic in central London. Last month, the Liberal Democrats adopted Livingstone’s transit policy, pledging to reverse the bus privatization imposed by the Thatcher government in the 1980s. They point to figures demonstrating a significant reduction in national bus usage, versus a whopping increase in London ridership since Livingstone took control of buses in 2000.

Livingstone remains the man to beat in the 2008 mayoral elections. The mayor himself notes how much has changed during his career by pointing to the Conservatives’ current search for a candidate to run against him. During the summer, rumours buzzed that Margot James, a lesbian businesswoman, would run. The current Tory favourite is Nicholas Boles, a think-tank director who is also openly gay.

The tables have turned, and Livingstone has the Conservative party — those evil architects of Section 28 ? engaged in their own frantic promotion of homosexuality.

***

Although Livingstone is not gay, he shares the experience of having been reviled and then accepted, despite unorthodox practices.

When I ask whether he ever made peace with Thatcher, he responds as both statesman and victor. “No. I mean, what she did was terrible and the human casualties were legion. But basically, when people get old and frail, you stop attacking them. That’s not fair.”

He has described his role in achieving gay civic partnerships as a proud moment in his career. I ask whether he worries that the gay movement will become too assimilationist, too bourgeois, too comfortable.

“No. No one should ever assume that because a man is gay, he will necessarily be progressive, any more than a black person might not be reactionary. We will only have a genuinely decent world where a gay man can be a really rightwing neo-con and a Muslim can be, you know, deeply reactionary, and we just don’t think there’s any problem with that. It’s not where you came from, it’s what you say today.”

Livingstone remains a radical in many ways, and yet he has come to embrace the virtues of commerce and big business. I’m curious to know how he sees himself in relation to his own success. Has he moved toward the mainstream, or is it the other way around?

“Any human being that hasn’t changed over 30 years would be a very sad individual,” he says with a grin. “But the big factor is that society has changed.”

The mayor’s tone becomes dour as he lists past controversies. “When I first advocated lesbian and gay rights in London, called for democratic accountability of police, said we should negotiate with the IRA, I mean, my poll rating went down to 18 percent. With the passage of time, people come to see these things are right.

“I’m lucky in the sense that, most politicians don’t get it ’til their 50s. I got it when I was 35, and, huge controversy. I was attacked on the streets and all of that, for saying these things.”

His face lightens. “But now, 30 years on, everyone says, ‘Well, Ken was right, wasn’t he?’ ” He suppresses a smile, but his eyes twinkle as he adds, “I like that.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra