Las Catrinas, signature characters of Dia de los Muertos celebrations, parade along Plaza Machado in Mazatlán. Credit: Natasha Barsotti

Overlooking the historic district of Mazatlán. Credit: Simon Koldyk

Guadalajara-born Mario Gonzalez Aguilar, 76, began cliff diving in 1962. Credit: Natasha Barsotti

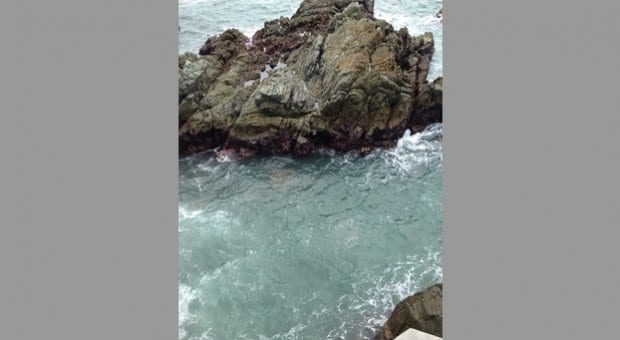

The 14-metre cliff from which divers plunge, just off the Olas Altas seawall in Mazatlán. Credit: Natasha Barsotti

A freshly painted gravesite at Panteón El Quelite, to the northeast of Mazatlán. Credit: Natasha Barsotti

A display of Catrina figurines at the Angela Peralta Theatre near Plaza Machado. Credit: Natasha Barsotti

This Catrina couple joined hundreds who took to the Plaza Machado and surrounding streets for the annual parade commemorating Dia de los Muertos. Credit: Natasha Barsotti

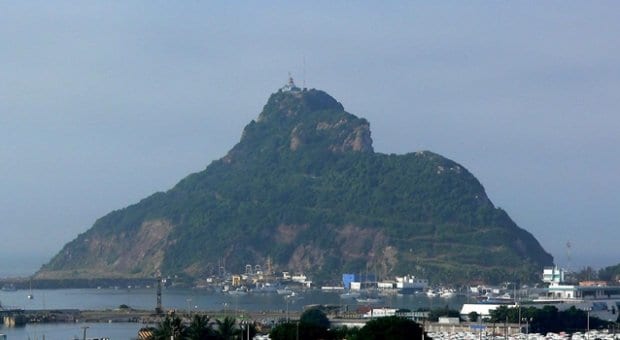

El Faro, Mazatlán’s famous lighthouse, began operating in 1879 and was once the highest lighthouse in the world. Credit: Stan Shebs

An altar de muerto adorned with sugar skulls, favourite tequila, foods and treasured personal items. Credit: Natasha Barsotti

Olas Altas. Credit: Simon Koldyk

Blanch-faced, dressed to the nines and ornately adorned with plumage, flowers and sugar skulls, las Catrinas sashay along Mazatlán’s crammed Plaza Machado to frenzied drumming, piercing trumpeting and firecrackers.

The pleasantly macabre signature characters of the annual Dia de los Muertos move among the sea of humanity that converges on the central plaza to jumpstart the carnival in honour of beloved departed relatives and friends, flirtatiously thumbing their noses at death or delighting in it.

The image of la Catrina, skull and bones wrapped in fine period fashion and elaborate head-wear, is associated with turn-of-the-20th-century Mexican illustrator José Guadalupe Posada, whose satirical work provided sharp commentary about race, making fun of Mexicans who aspired to be European in appearance and culture.

But it was artist Diego Rivera who took Posada’s image and turned her into “an icon of Mexican-ness,” geography professor Juanita Sundberg says. “That was what his work was about, creating this idea of a Mexican national identity, situated in its pre-Columbian and folk roots. He is reportedly the one who called her La Catrina.”

As Posada and Rivera have demonstrated, the Catrina image can be leveraged to make an array of statements, political and otherwise.

From the sidewalk patio of the Plaza Machado’s bustling Pedro y Lola restaurant, I wonder if I’ll see any genderbending Catrinas. I don’t have to wait long to spy one or two amidst the promenading heteronormative calavera (skull) couples, some rushing — plastic cups in the air — to catch up with the burro-drawn carts of free beer that the “bartenders” are dispensing hand over fist.

“You can see how the image would lend itself to drag. It’s supposed to be all about playing with costume and playing with your identity. That’s what Posada was talking about, even though he wasn’t commenting about gender identity or sexuality,” Sundberg says.

• • •

The dead are very much part of life, and they have it made, at least on the first two days of November — Dia de los Angelitos (Day of the Innocents) followed by Dia de los Muertos, the day of remembrance for adults who have died.

Walk into restaurants, artists’ studios, businesses or homes and altares de muertos (altars to the dead) are front and centre, decorated with banderillas (small flags), bread of the dead, tequila, fruit, skulls of sugar and clay, and specific effects treasured by the deceased.

In Mazatlán’s historical centre, the storefronts of flower shops, some almost three generations old, are a riot of blooms, including cempasúchil — otherwise known as the Mexican marigold — touted as the ideal flower to adorn loved ones’ final resting places.

As Dia de los Muertos approaches, the panteones (cemeteries) are anything but sites of sadness and regret to be avoided. They are a flurry of preparation and anticipation: one or two children run in and among the graves, which have been swept, weeded and given fresh coats of paint.

Entering the cobblestoned, colonial city of El Quelite, about 40 kilometres northeast of Mazatlán, a handful of families are in vigil mode in the local panteón, patiently awaiting the arrival of recent or long-gone loved ones whose favourite foods, drink, books and other personal items are laid out to entice them to a celebration of their lives.

“It’s about saying, ‘We honour the dead.’ It’s saying that our dead are with us, and we memorialize them,” Sundberg says.

• • •

The seeming absence of fear of the hereafter, or of mortality itself, extends into everyday life itself.

Situated along the six-and-a-half-kilometre seawall, Olas Altas, is a 14-metre rock where cliff divers literally throw caution to the wind that whips around its height and crevices.

Below, the churning waves submerge and expose the rocks below.

Timing is everything, the story goes. As the waves come in, there is ideally just over two metres of water to execute a safe, head-first dive. Absent the “right” wave, the depth is a little more than a metre.

A mini-figurine of Mary and some flowers are tucked into the mid-section of the outcrop in memory of the last diver who, in 2006, did not emerge alive. It serves as a reminder, but hardly a deterrent, to fellow divers, who carry on — for the right price.

Approached at night, both rock and diver are shrouded in darkness, except for the fiery flares the latter brandishes to induce takers.

Guadalajara-born Mario Gonzalez Aguilar, 76, first flirted with cliff diving in 1962. He has taught almost every diver in Mazatlán the tricks of the trade.

While he stopped diving — for health reasons —four years ago, he is eager to take the plunge again.

Perched on a ledge on the landward side of the cliff he has mastered, Aguilar, with pet iguana astride his left shoulder, shrugs off questions about the risk of his profession and rejects any notion of fear.

He has no logical answer to give. It’s just his life and a way to make a living.

• • •

Mazatlán is about a five-and-a-half-hour drive northwest of Puerto Vallarta. For the most up-to-date travel information on gay Puerto Vallarta, see our City Guide, Listings Guide, Events Guide and Activities Guide.

Mazatlán is about a five-hour-and-15-minute drive north of Guadalajara. For the most up-to-date travel information on gay Guadalajara, see our City Guide, Listings Guide, Events Guide and Activities Guide.

For a real adventure along Mexico’s west coast, make the 18-hour drive south from Tijuana. For the most up-to-date travel information on gay Tijuana, see our City Guide, Listings Guide, Events Guide and Activities Guide.

For more information on Mazatlán, visit gomazatlan.com and allaboutmazatlan.com.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra