Hotel Castelar was one of the early hotels that was openly gay-friendly, perhaps in part because of the Turkish sauna in the basement. Credit: Michael Luongo

Boys hang out poolside at the Axel Hotel. Credit: David Walberg

Tigre islands on the Paraná Delta was integral to the development of Argentina’s gay rights movement, with LGBT groups meeting out of the reach of various dictatorships over the years. Credit: Michael Luongo

Carlos Daniel Franco runs two locations of the popular Pride Café. Credit: David Walberg

On weekends, tourists head to the San Telmo district for art shows and antique fairs on Defensa Street. Credit: de Benutzer Zenfea

A man stands outside the Congreso building on Avenida de Mayo draped in a rainbow flag; the building was the location of gay rights protests. Credit: Michael Luongo

María Rachid, former head of the LGBT Federation of Argentina and now a Buenos Aires city legislator. Credit: Michael Luongo

Recoleta cemetary. Credit: Andrew Currie

Marcelo Suntheim (left) and César Cigliutti, head of the rights group Comunidad Homosexual Argentina (CHA). Credit: Michael Luongo

The Cabildo of Buenos Aires on the Plaza de Mayo. Credit: Herbert Brant

When President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner signed the same-sex marriage law in the Casa Rosada, she called Argentina a “beacon” for LGBT rights in Latin America and the rest of the world. Credit: Michael Luongo

Plaque at Castelar Hotel commemorating gay Spanish playwright Federico García Lorca’s stay at the hotel; his room has been made into a mini-museum. Credit: Michael Luongo

Tres Bocas is a sleepy, secret hideaway. Credit: David Walberg

“Don’t Cry for Me, Argentina,” from Evita, is the song that often comes to mind when thinking of Buenos Aires, especially for a gay man planning a visit. On my first trip back in 2000, I was the one who left crying for Argentina.

That Buenos Aires adventure was part of a multi-country backpacking trip through South America. I started in Rio for Carnival, the world’s most famous party, and ended with a scientific cruise through the Galapagos during Easter week. Looking back, the time frame corresponds roughly to the Catholic holiday of Lent, but I didn’t deny myself anything during that whole trip.

And that’s why I was crying when I left Argentina. Of course, it involved a guy I had met, too.

His name was Mario. He was one of many men I would meet in Argentina, and the rest of the countries on that trip. (To be young and in shape again!) Yet the special circumstances of that evening — his 29th birthday, which he was celebrating with friends at the Oxen, a club that no longer exists, on my last night in his hometown — made it all the more memorable.

When I left his apartment that rainy morning after, Mario promised he would see me off when I took the Manuel Tienda Leon bus service back to the airport. We had already become more than just tricks to each other. Though his partners over the years wound up hating me, Mario turned into a lifelong friend, even if we never experienced again what we did that night. In recent years, we content ourselves with lunchtime meetings, making sure to dine somewhere his jealous partner will never catch us. It’s all very innocent now, but that original adventure became the chapter “The Eyes of Caravaggio” in my 2003 Haworth Press book Between the Palms, which I dedicated to Mario.

And, as it was with Mario, my relationship with his city turned out to be far more than just a one-night stand.

I became the author of the Frommer’s Buenos Aires book, moving back and forth between Argentina and the United States over the years. Ultimately, I would work on nine books for Frommer’s focused on Buenos Aires while penning countless articles for other publications, gay and straight.

I don’t cry anymore, but each time I leave my beloved Buenos Aires, I feel a deep sadness. And I have seen the city change over the years. Some changes have made me happy; others have made me sad, especially as more and more foreigners make learning Spanish unnecessary.

Among the changes is the way that Buenos Aires, and Argentina as a whole, has become a much more progressive place for gay men and women. There was always a large gay infrastructure — bars, clubs and restaurants — but watching the legal changes has been especially interesting.

The first was the passing of civil unions, which became the law in Buenos Aires in 2003, eventually spreading to most of the country. The original legislation was brought up at the end of 2002, something that César Cigliutti, head of the rights group CHA (Comunidad Homosexual Argentina), told me was a Christmas “gift” from the government. It was this status quo that the current Pope Francis, formerly Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio of Buenos Aires, had tried to maintain in Argentina when full gay marriage passed in 2010.

President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner often butted heads with Bergoglio over LGBT rights. When she signed the same-sex marriage law in the Casa Rosada, she called Argentina a “beacon” for LGBT rights in Latin America and the rest of the world. The passing of the law by chance coincided with that year’s G Networks gay travel conference, run by Pablo de Luca and Gustavo Noguera. I was invited to attend the ceremony as a VIP along with the rest of the conference speakers. Afterward, President Fernandez held a private meeting with us in her office, eager to chat with the foreign delegates, telling us she believed Americans might start moving to Argentina, seeking out the freedom to marry.

While I don’t personally know any Americans married under the Argentine law, anecdotal evidence suggest she’s right about foreigners moving to take advantage of it. In fact, earlier this year, the residency requirements for foreign couples marrying in Argentina were loosened, allowing travellers to get married and turn their vacations into honeymoons. This might not sound remarkable to Canadians (Canada has permitted foreigners to do this for nearly a decade); still, I find the fact that Argentina has leapfrogged into being a leader on LGBT issues astounding.

I don’t agree with Fernandez on everything; in fact, I think Argentina’s continually plummeting peso and re-emerging economic crisis, a normal cycle for the country, might be one more sign she’s wrong on economics. She is also known for confrontations with Argentina’s indigenous people. However, she was right about Argentina becoming a beacon on LGBT rights for the region. Mexico City soon followed suit, passing a same-sex marriage law. It’s become part of the conversation in neighbouring Chile, a country once so conservatively in the grip of the Catholic Church that divorce became legal only in 2004.

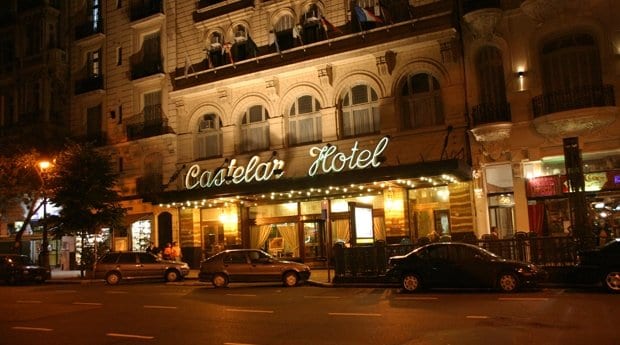

All of this is a long way from the city I first visited in 2000, where few hotels were openly gay-friendly. The historic Castelar Hotel on Avenida de Mayo was among them, a result of its historical affiliation with gay Spanish playwright Federico García Lorca and the Turkish sauna in its basement. In addition to the plaque commemorating Lorca’s stay, the room he stayed in was made into a mini-museum.

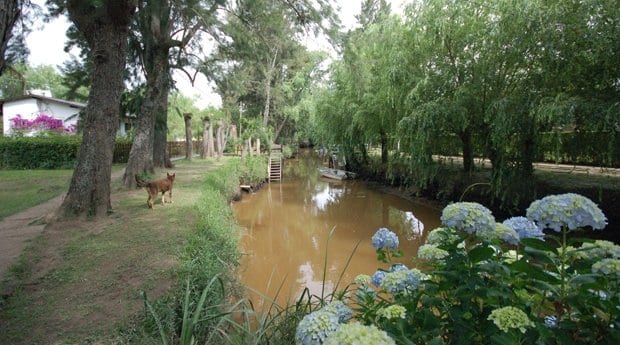

Now, when hotel managers learn I am gay and that I work for the gay press, they demand I describe their hotels as gay-friendly, even if it has nothing to do with the article at hand. The request comes from trendy hotels in Palermo Viejo, like the Soho All Suites, and luxury resorts on the Tigre islands, on the Paraná Delta, an hour from Buenos Aires. Tigre is technically part of Buenos Aires’ suburbs but feels remote because of the waterbound method of transportation required to reach it; the area was integral to the development of Argentina’s gay rights movement, with LGBT groups meeting out of the reach of various dictatorships over the years.

Gay visibility has exploded in the time I have been writing about Argentina. The annual national Pride march, Marcha del Orgullo, was once a tiny affair. The event has grown exponentially in size and media attention as same-sex marriage and other legal milestones were reached. It’s usually the first or second Saturday in November, the date marking the founding of Nuestro Mundo, “Our World,” Argentina’s first known gay rights group, in 1967. Manuel Puig, the author of Kiss of the Spider Woman, was an early member.

The late-spring event (Argentina’s in the Southern Hemisphere) starts with a Pride fair at 3pm in Plaza de Mayo, in the shadows of Evita’s famous balcony at the Casa Rosada. It’s the usual, with booths rented by LGBT groups, vendors, booksellers and others interested in reaching the gay community.

The parade steps off at 6pm from in front of the Catedral Metropolitana, where Bergoglio once reigned. The world seems to forget how anti-progressive he was on LGBT and other issues as archbishop of Buenos Aires, in spite of his work with the poor. The cathedral’s façade was often marked by graffiti and splatter bombs of red paint representing blood on the church’s hands while he was its head.

The parade heads up Avenida de Mayo to the Congreso building for a rights rally with onstage entertainment, including gay couples doing the tango. When I first witnessed the parade, it was tiny at its start, growing in size only as darkness fell, allowing attendees a sense of anonymity. Now, the beginning is crazily crowded. Even burly union leaders jostle for camera face-time, next to nearly naked transgender beauties, to show off their progressive credibility to the country. María Rachid, former head of the LGBT Federation of Argentina and now a Buenos Aires city legislator, is always one of the rally’s leaders. When I first started living in Argentina, the rally was a protest against Congress, the stage set up across the street facing it. Now, the rally is held on the steps of the building, welcomed as an official cultural event by the city.

Argentina has come a long way in my more than 14 years of writing about and living in the country, transforming itself from a secret for those in the know into one of the world’s most important gay travel destinations. It has been a beautiful thing to witness.

For the most up-to-date travel information on gay Buenos Aires, see our City Guide, Listings Guide, Events Guide and Activities Guide.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra