By the time he enrolled in BC’s Christian evangelical university, Jacob was already deeply in the closet.

Reluctantly, he’d admitted the truth to himself when he was 14. He liked boys. But he didn’t dare tell anyone in high school. How could he? His peers had threatened to kill him on the mere suspicion that he might be gay.

“We hate everything about you and you better watch your back because we’re going to kill you on your way to school,” a fellow student messaged him online.

By the time he set foot on Trinity Western University’s small campus in the suburban community of Langley, BC, he was determined to keep his sexuality a secret.

“It felt like if I didn’t talk about it, then it might not be real,” he says.

I meet him in December 2016, at the end of semester in one of a handful of low-rise buildings scattered around TWU’s leafy campus, located about 45 minutes east of Vancouver in BC’s Bible Belt.

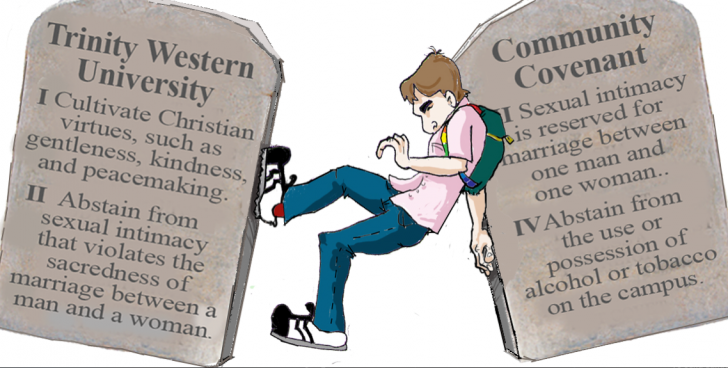

The rules at TWU have made headlines in recent years, as the school’s now-infamous community covenant strictly forbids homosexual activities or any form of “sexual intimacy that violates the sacredness of marriage between a man and a woman.”

Of course the covenant also prohibits lying (and other supposedly un-Christian acts like adultery, gossiping and booze), leaving students like Jacob in a double-bind.

Though it’s shifted over the years from a signed document to a box checked online, every student and teacher at TWU must pledge their allegiance to the covenant every year.

As Jacob and I roam the halls searching for an empty classroom in which to conduct our interview, I’m mindful of the risk he’s taking to share his story. My camera bag bumps conspicuously against my leg with each step. I tuck my notebook away. Finally, we find a classroom we can use.

We close the door and I agree to withhold his name and identifying characteristics for this story. Jacob is not his real name. Still he seems nervous during our interview, and sometimes asks to speak off the record.

He tells me about another moment in another classroom, feeling pinned under an unwanted spotlight as his classmates suddenly focused on him, wondering out loud who he’d rather sleep with, men or women? He tells me about the TWU teacher who was in the room and who did nothing to intervene. Feeling trapped, Jacob says he once again ducked the question.

I met Jacob through a handful of Trinity Western alumni that I interviewed for this piece earlier last fall. When I asked each of them if they knew any openly queer students currently attending TWU who might be willing to share their experiences, they were skeptical.

They said they would ask around but warned me not to expect much of a response. Current students likely won’t want to rock the boat, they said. They were right.

Jacob is one of only two queer students currently enrolled at TWU who contacted me. According to its website, Trinity Western boasts a student population of 4,000.

I ask how he felt when his classmates grilled him about his sexuality. He says it’s difficult enough trying to figure out his own sexuality without having other people project their assumptions onto him.

“I loved the community here so much that I didn’t want to jeopardize those relationships,” he says.

He acknowledges that non-religious queer people also risk losing friends or family members when they come out. But it’s different in a Christian context, he says; the risk of rejection is amplified.

He tells me that he has been wrestling with his feelings about Trinity Western. First he says it’s a great place to go to school. This is where he got his undergraduate degree, and he has now returned to complete some prerequisite courses in order to enroll in the education program. The professors and students here are “amazing,” he adds.

He says he wants to continue his studies here, but he changes his mind every week.

“There definitely are things on campus that I hope wouldn’t be the case everywhere else,” he hesitantly admits.

He remembers walking across campus one day and overhearing a group of students laughing about someone’s “lesbian haircut.” He wanted to object but couldn’t say a word.

Other campuses are rife with homophobic comments too, I want to assure him, though most now have queer resources, rather than a covenant that explicitly forbids same-sex relationships.

Trinity Western’s covenant has sparked controversy across Canada for years, especially since the university announced its intention to open a law school in 2013.

Many lawyers objected to seeing future members of their profession trained on a campus governed by what they consider a discriminatory policy against LGBT students.

Several provincial law societies have outright refused to accredit the school’s future grads. (Ontario said no, BC initially said yes then changed its mind, and Nova Scotia said it would only recognize TWU’s grads if the school changes its covenant.)

The question is now making its way through several court cases, which have so far all yielded different results. In a June 2016 ruling in Ontario, the justices found TWU’s covenant discriminatory and said LGBT students deserve equal access to law school. A month later, Nova Scotia’s court of appeal sided with TWU, saying the school is entitled to its religious freedom. Five months after that, BC’s court of appeal sided with TWU as well. The evangelical school has a right to its beliefs, the court ruled, even as it acknowledged that the covenant is “deeply offensive and hurtful to the LGBTQ community.”

The Supreme Court of Canada has now decided to weigh in on the appeals with what is sure to be a landmark ruling in the case. The judges’ decision will likely determine whether graduates of an evangelical law school can practice as lawyers in Canada.

And as the court prepares to deliberate, the covenant continues to hover over students and staff at Trinity Western, stifling not only their sexuality but their ability to openly discuss the topic at all.

Queer students, past and present, tell Xtra that when they speak out about homosexuality, they’re met with suspicion, hostility and even outright censorship from TWU’s administration.

When Jacob first started at TWU, he tried to live by the covenant. First he stayed celibate. Then he tried dating women.

“Being a student leader on campus means you have to agree to not just live by the community covenant, but help others to live by the community covenant,” he says.

I ask him if he feels like he has violated the covenant now.

“Initially, for most of my undergrad, I felt like I was upholding the covenant. I would say I am still upholding the covenant,” he says. “I’m not dating, and even if I was dating someone of the same gender, it wouldn’t actually break the covenant.”

But doesn’t the covenant prohibit same-sex relationships?

“It says that you can’t have sex,” he points out. “So, if you aren’t having sex, you wouldn’t be breaking it. And if you were, I think some people would just be like, ‘Well, I know that there’s straight people having sex, too.’”

Corben meets me in the parking lot by the tennis courts and together we walk across campus to the theatre department, me in my Blundstones and Corben in his glittery Doc Marten-style boots.

We sit down in an empty dressing room. The first half of our interview is sprinkled with pauses as we wait, or lower our voices, whenever anyone walks by the closed door.

Though Corben seems more comfortable than Jacob, he still asks that his last name not be published.

He tells me he’s from Valleyview, Alberta, population 1,972. Like many queer youth who grow up in small towns, Corben moved away to an urban area as soon as he graduated from high school, so he could live openly as a gay man.

For four years, he did just that. He moved in with a supportive cousin in Abbotsford, about an hour east of Vancouver, found a job in customer service, made friends, went to parties and loved the downtown nightlife.

He also gave up his faith during this time. His family and community had told him that he couldn’t have a relationship with God and be gay.

Then, in 2014, he enrolled at Trinity Western University, largely because it was the only university his parents would pay for.

“My parents, I think, kind of wanted Trinity to be for me sort of like reparative therapy, which is why they would only help financially with this school,” Corben says. Reparative therapy refers to the now-discredited and increasingly banned practice of trying to convert or “cure” queer people of their sexuality.

His parents did not trust a secular drama department because they thought it would nurture his homosexuality.

Corben came out to his family when he was 18, shortly after graduating from high school. He had come out to himself years earlier, watching YouTube videos late at night after his family went to bed.

He still remembers the first image he found of two women kissing on YouTube. He hadn’t known that people of the same sex could behave that way. Later that night, it occurred to him that YouTube might also have videos of two men kissing. They weren’t that hard to find.

“That’s when I knew — because I just continued to watch,” he says. “It revolted me. Growing up in a Christian home you’re just like, ‘that’s not allowed.’”

But his mom was tracking the family computer.

She eventually stumbled across some messages that Corben had sent his boyfriend at the time over Facebook.

His family has since told him that his partner will never be welcome in the family home, that they will never attend a gay wedding for him, and that they’ll denounce his sexuality to any children he might have in the future.

“I know their love for me will never go away, but that’s not going to stop them from never talking to me again.”

He prayed for six years to change his sexuality. Unsuccessful, he now considers it a sign from God that nothing is wrong with him. Though if God had granted his prayer to be straight, he says he would have gladly accepted.

Corben says he’s only had positive experiences on campus related to his sexuality, but suggests that students who are still struggling with their sexuality when they arrive at TWU, or who discover they’re queer while on campus, may feel isolated without support.

“I haven’t had a lot of people who are searching and closeted come to me, but I do get a few,” he says. “I try to help them the best I can. They just want answers, and I tell them I can’t give them answers . . . I tell them that no one is going to know this answer until we’re standing face-to-face with God.”

I reach Ren Lunicke via Skype in New Zealand. Lunicke graduated from Trinity Western in 2007 and remembers quietly signing the covenant in their first year.

“I believed the covenant and didn’t think it was a big deal to follow it,” says Lunicke, who now uses the gender-neutral pronoun they. Back then, Lunicke had a boyfriend and identified as straight.

By second year, a somewhat emboldened Lunicke, who had fallen in love with a woman at school, signed the covenant but crossed out the parts they didn’t agree with.

At first, Lunicke thought they had gotten away with it. But when they tried it again the following year, TWU administrators intervened and asked Lunicke to meet with a counsellor.

Lunicke sidestepped the intervention by submitting a signed but still-amended form to a different registrar.

But other queer students sought counselling to try to “get better,” Lunicke says.

TWU encouraged students to seek reparative therapy, and brought in speakers to chapel sessions who talked about homosexuality and how “God’s love can bring you out of it,” Lunicke alleges.

Even over Skype, Lunicke’s frustration towards Trinity Western is palpable. They are adamant that the school is not a safe space for queer students, and they are determined to push for change.

The atmosphere on campus stifles students’ sexuality and self-exploration, Lunicke says. Some students really struggled to reconcile their feelings with their learned sense of shame.

“I was terrified while I was attending the school that at any point I could be found out,” Lunicke says. “Nearly all of us had a reverberating effect for years after finishing at Trinity that made it difficult for us to get away from the shame.”

“We might be out and proud, but then we have to put so much separation between us and our upbringing, our friends from that time in our life.”

Lunicke, who studied theatre and psychology, remembers one class where a professor started a debate about whether homosexuality, as defined by Christian values, should be labelled a mental illness.

“They have incredible power to tell people that their natural experience of themselves in the world is wrong, and if you’re not ashamed of it and if you’re not trying to fix it, then you don’t belong and your experience doesn’t count,” Lunicke says.

The overall message Lunicke says they received from TWU staff was that queer culture is morally bankrupt, flagrantly sinful and not just bad for Christianity — but bad for the world.

TWU’s president, Bob Kuhn, a practicing lawyer for over 30 years, is no stranger to defending religious rights.

In 1997, an elementary school teacher named James Chamberlain wanted to use three books depicting families with same-sex parents in his kindergarten classroom in the Vancouver suburb of Surrey, BC.

Kuhn’s law firm represented the Surrey school board in the ensuing legal battle, after it refused to allow the books into its classrooms. The board claimed that children were too young to learn about homosexuality, and that schools should not use books that conflict with some parents’ religious beliefs. In 2002, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled against the board, stating that “tolerance is always age-appropriate.”

Two years before Chamberlain’s request precipitated the Surrey book-banning battle, TWU had applied to the BC College of Teachers to accredit its teacher-training program. Like the lawyers associations would do nearly 20 years later, the teachers’ association rejected TWU’s application, saying the school’s covenant violates its anti-discrimination policy.

Kuhn represented TWU in the case and led it to victory when the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in its favour in 2001. The court found no evidence that teachers trained at the evangelical university would discriminate against gay and lesbian students in their classrooms. TWU now offers a five-year teacher education program.

In 2005, Kuhn’s firm also represented the Canadian Religious Freedom Alliance in the Kempling versus British Columbia College of Teachers case. Chris Kempling was a high school counsellor in the northern town of Quesnel, BC, when he was suspended by the BC College of Teachers for sending anti-gay letters to the editor endorsing reparative therapy. This time the teachers’ college won. Kempling left the public school system three years later, after the college accused him again of conduct “unbecoming” of a teacher.

According to his TWU bio, Kuhn studied at TWU in the early 1970s before pursuing his undergraduate and law degrees at the University of British Columbia. While at TWU, he served as student-body president.

Kuhn was awarded an honourary doctorate from TWU’s board of governors in 2012. He was also president of the TWU Alumni Association at the time.

He stepped in as interim president in 2013 and was then named president and vice chancellor of the university in March 2014, three months after TWU got preliminary approval to open its proposed law school. (Under pressure, BC’s education ministry rescinded its approval one year later.)

Kuhn calls me on a Saturday evening in January to talk about life for queer students on campus.

I ask him about the covenant.

He says it’s unfair to characterize the university or its covenant as unfriendly to gay students.

“The basic principle is that we believe marriage is, in a biblical context and a Christian context, between a man and a woman, so sexual behaviour outside of that . . . is something that we don’t agree is correct,” he says.

Some students are afraid of backlash from the administration if they speak out, Jacob suggests, when I ask him why only two students responded to my request for interviews.

Jacob says he and other students were encouraged to speak with Kuhn before ever talking to media.

Alexandra Moore, a queer TWU alumni, says she faced discipline for challenging the covenant when she was a student at the university from 2000 to 2007, prior to Kuhn’s arrival.

She says she was working as a teaching assistant when she wrote an article in favour of same-sex marriage for the student newspaper, Mars’ Hill. Shortly thereafter, she says, she was pulled into the office of the professor she was working for and nearly fired.

In a detailed post about her years at TWU, Moore, like Lunicke, says the school is not a safe space for queer people. She says students are discouraged from openly expressing any views inconsistent with the beliefs of evangelical Christianity.

She tells me that she chose not to be publicly out about her sexuality while attending TWU because her she didn’t want to jeopardize her career. Like Corben, her family would only financially support her if she stayed at TWU. “It was a practical move for me,” she says.

Interestingly, after her Mars’ Hill story was published, another professor wrote a piece in the newspaper’s following edition that was also in favour of gay rights. Moore says it was the first time she had seen a professor publicly voice their support; she believes that most staff chose not to for fear of losing their jobs.

Kuhn tells me he has a good relationship with students on campus, and denies the allegation that he encourages students to speak with him before speaking to the media.

Although, he says, if he has a good relationship with a student, he would rather they come speak to him without involving the media. But there is no school policy on speaking to the media, he says, adding that he has extended an open invitation to journalists who would like to visit the university’s campus.

“It’s a pretty casual environment,” he says. “It’s not like there’s a heavy-duty administrative imposition of rules and regulations.”

“People come to talk to me about all kinds of things,” he continues, “including their sexual identity or issues related to homosexuality.”

Kuhn says he has not dealt with a single case of someone who has breached the covenant’s prohibition against same-sex relationships in his four years as president.

Ultimately, he says, each student makes a personal choice to join the TWU community.

University spokesperson Amy Robertson echoes Kuhn, saying the school’s administrators are open and responsive to all students, including queer ones. “I can speak specifically for the president, because I work with him closely, that his door is open to talk and share their stories,” she tells me by phone in January, two days before leaving her position at the school.

Robertson said the covenant is not about punishing people. “It’s about learning together and growing together.”

“Our goal is for students to stay and have a positive time here,” she said. Many students choose to attend TWU because of the covenant, she added, as it “creates the kind of safe community space they’re looking for.”

If anyone does violate the covenant, “there’s an accountability process in place.” The process is determined on a case-by-case basis, she explained: it might mean having to speak with the director of student life, or completing an educational project such as writing an essay.

“To put that type of moral requirement for getting a university degree is problematic,” Moore contends. “But that’s part of why my parents were comfortable with sending me there.”

Nicholas Noble, who graduated from TWU last year, alleges he was quickly pulled into a meeting with Kuhn when he publicly challenged the covenant.

Noble was skimming Facebook in July 2016 when he read a post by a TWU graduate on the university’s law school battle and how the covenant could potentially be reworked to build bridges on campus.

Skeptical, Noble, who describes himself as a straight ally to the LGBT community, posted a long reply critical of the university.

Within just a few hours, the president of the university himself had replied to Noble’s comment.

Kuhn questioned Noble’s definition of community, then suggested a meeting. “Perhaps we could get a time to discuss this when you return, rather than rely on well written, but perhaps overstated, argument and accusation. Just my opinion though. Would love to sit down and have a coffee,” he posted.

Noble says he was surprised that the university’s president quickly and publicly refuted his comments. But “Bob Kuhn never rescinds or drops his lawyer persona,” Noble says. Partly it’s a personal touch, Noble acknowledges — “at the same time, it was 1984 Orwellian-esque.”

“Typically, if a student at a secular university has complaints with ethical issues at a university, there are departments you can go to. There’s a sense that there’s a human resources department or a designated person in student life you can talk to,” Noble notes. “But at TWU, when you have an ethical concern about how the university is being run, you are directed directly to the president.”

Noble alleges that Kuhn sends Facebook friend requests to most TWU students.

Noble ultimately accepted Kuhn’s invitation to have a meeting because, then on the cusp of graduating from TWU and flying to Toronto to start a new chapter, he seized the opportunity to finally voice his complaints.

Noble says the main focus of the meeting was how queer students are being treated on campus.

According to Noble, at the meeting Kuhn asked him to prove that TWU is a hostile environment to queer students.

When Noble said that some TWU professors sympathized with queer students, and that some were looking for jobs elsewhere, Noble alleges that Kuhn asked him to name dissenting faculty members. Noble says he refused, and left the meeting feeling “confused and dumbfounded.”

I contacted TWU spokespeople Amy Robertson and Ann Coats again on Feb 8, 2017, to schedule a follow-up interview with Kuhn to ask him about Noble’s allegations. But after an initial reply from Coats asking what the allegation was about, and my reply that I would rather speak to Kuhn directly to give him a chance to respond, I didn’t hear back. I followed up again a week later to no response.

During our initial interview, Kuhn told me, “I don’t know any other university that has the president of the university meet with students every day, multiple times a day.”

“It’s a unique place.”

It’s certainly rare to see a university president engage so directly with his students on Facebook.

Even as TWU administrators try to control the narrative and keep conflict out of the public eye, some students and grads are taking it upon themselves to create space for their queer peers to speak.

Alumnus Matthew Wigmore helped run the Facebook group One TWU, to support LGBT students safely exploring their sexuality and faith on campus, and to encourage the university to amend its covenant to “reflect the diversity of opinion regarding same-sex marriage within the Christian Faith.”

He’s quick to distance the online group from the administration.

“The goal of One TWU is completely independent of any conflicts the TWU administration finds themselves in,” he writes in an email to Xtra.

“We seek to create an emotionally and physically safe space on campus for students to journey openly with questions of sexuality, which are otherwise ignored or pathologized.”

TWU can’t control conversations that happen online, Lunicke says, so “this is where the admin as an old regime is losing the battle, and maybe this war.”

Some students are taking tangible steps on campus, too. The student government organized an event on Nov 23, 2016, where students read aloud stories from queer TWU students.

“It was amazing,” says Jacob, who estimates that more than 300 people attended. He says the stories told revealed a mix of positive and negative experiences on campus. But of the approximately 15 stories shared, only one person was willing to read their own. All other testimonies remained anonymous.

“It speaks to the culture at Trinity that there really is this fear underlying,” Jacob says.

“It’s kind of like a last stance on a culture war,” he suggests. If Trinity Western relents on its covenant and its opposition to same-sex relationships, he says, “a lot of people will feel like the evangelical Christian world has lost.”

Corben says Christianity itself may be shifting. When it comes to the covenant, TWU is “fighting so hard for this thing,” he says, but “generations are changing in their ideologies and their views and in their Christianity as well.”

I am sitting in a classroom at my own university when, two months after our first interview, Jacob calls to tell me about the latest “Facebook explosion.”

He says an unofficial Facebook account called Trinity Matchmayker (now deleted), whose apparent aim is to pair students together, has released its latest list of student couples.

“One of my friends, bless his soul, commented: ‘Sounds heteronormative, but okay!’”

Jacob says the Matchmayker account responded to the comment by posting an excerpt from the Bible.

“I’m going to paraphrase, it was something like: ‘if a man should lay with another man like he does a woman, it’s an abomination and he should be put to death and his blood should be on his own hands,’” Jacob says.

“Even from a conservative Christian perspective, that’s a weird verse to choose,” he says. “Why not choose a verse that defines marriage as being between a man and a woman. Why do you have to choose one about execution?”

I ask Jacob if he thinks it’s okay to be gay at Trinity Western now.

”I don’t know,” he says. “I wish I could give a straightforward answer. I want to say that I know some queer students who have had an amazing experience — and just last night, I saw somebody crying and talking about how it was anything but a safe space.”

Several weeks pass before I check in with Jacob one last time.

To my surprise, he tells me that he has come out publicly and has a boyfriend now, whom he met online in a Facebook group for gay Christians.

He is no longer a student at Trinity Western.

Had he stayed on campus, he would have had to become a vocal advocate for LGBT students, he says, and he doesn’t have the energy for that.

“I’m good with having my calm season of life to figure things out,” he tells me by phone.

He says he’s cultivating more safe spaces in his life.

“Trinity couldn’t be that for me.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra