Behind a Plexiglas window at Ottawa Carleton Detention Centre (OCDC), an HIV-positive gay man picks up the telephone for his fourth interview with Xtra. He’s accused of not disclosing his poz status to sexual partners on more than a dozen occasions; he now faces more than two dozen charges.

Dressed in the prison-issued bright orange jumpsuit, he is clean-shaven and his hair has grown much longer. He is in good spirits after his daily 20-minute outdoor time.

“I haven’t had a haircut since March,” he says.

The accused talks about his experience in protective custody. Some fellow inmates recognize him and hurl threats like “I’m going to kill you, motherfucker, when I get out.”

“It’s very scary. It’s very real,” he says.

“Karen,” a sibling of the 29-year-old Ottawa man, says her brother has been reaching out for help for many years. Karen says her brother was a needy child and required more attention and love than her parents could provide.

Mental health and substance abuse problems run rampant in her family. Her mother suffers from anxiety, and her biological father has substance abuse problems.

After her biological parents split, her mother married Karen’s stepfather, a recovering alcoholic and medicated schizophrenic. They had four children together, including the accused. At 13, he moved in with his maternal grandparents.

When he was a teen, Karen says, her brother always had permission to use his grandmother’s debit card. But she says her brother felt isolated then and had few friends, mostly girls. She said he had temper tantrums: stomping, yelling and shaking his hands — behaviour she felt he should have outgrown.

But Karen says her brother served on student council and earned good enough grades to attend Laurentian University. Due to illness, his university education was cut short. She says her brother would have finished school — if he had attended university closer to home, where his grandmother could have taken care of him.

The accused was 22 when he told Karen he was gay. She says she did not know, but looking back, he never pretended to have girlfriends. His grandmother, a devoted Catholic, repeatedly tried without success to introduce him to women.

In his early 20s, Karen says, her brother became popular — a contrast to the isolated child she had known. He dated and was connected to Ottawa’s gay community. He was always meeting a friend or partying. She also says this is when her brother started drinking to excess.

In 2007, Karen’s grandmother died and her brother took it hard. She says his drinking got out of control, but he saw a counsellor and often talked about advice he was given. At this point, she says, he was beginning to act responsibly, understanding how his actions made others feel. He was also working for the government, on short-term contracts in call centres or in clerical roles.

Karen fears jail will only exacerbate her brother’s mental health issues. When she asked his lawyer, Delinda Hayton, if he would get the help he needs in prison, Hayton replied, “That’s not what the justice system is for.”

The accused says he does not agree with his family that he has a drinking problem but admits drinking gets him into trouble. He does not feel he has mental health problems, but he is taking Seroquel to ease his anxiety.

Since the accused was imprisoned on May 6, he says Michael Burtch, the MSM Community Developer for ACO, has provided consistent emotional support. He is grateful for Burtch’s encouraging words, but that is the extent of the HIV support he gets, a condition he was diagnosed with just last November.

He is isolated from other prisoners. In June, a doctor ran HIV tests and recommended a course of treatment, but he is still waiting for it. In prison, he says, getting HIV treatment is up to him. When he did go for it while in Ottawa, he felt embarrassed, transferred to the General Hospital in shackles, ushered through the building in an orange jumpsuit with a guard on each side.

“Correctional Services of Canada (CSC) is one of the five stakeholders working in the HIV strategy in Canada. They get enormous funding from the government because that’s where the HIV care money is allocated. A good chunk of the money is for education, prevention, support and care,” says Trevor Gray, PASAN youth and outreach education coordinator.

Gray says healthcare in prison is not a priority because it is about incarceration; security for both jail workers and inmates is. Gray also says HIV stigma in prison is a serious problem.

“If you’re in prison and you want to fuck but there are no condoms, you’re going to fuck anyway. We’re talking about a prison, not talking about an AIDS organization where you can get clean needles, crack kits and talk about sexual orientation. That’s not what happens in prison. And if you’re worried about being stigmatized, you may choose to go into isolation because you don’t want to disclose your HIV status. It’s going to disrupt your life. You may be sharing a cell with someone who doesn’t have the knowledge. And while you’re telling a healthcare worker what you need, it’s not confidential if there are 10 people within earshot,” says Gray.

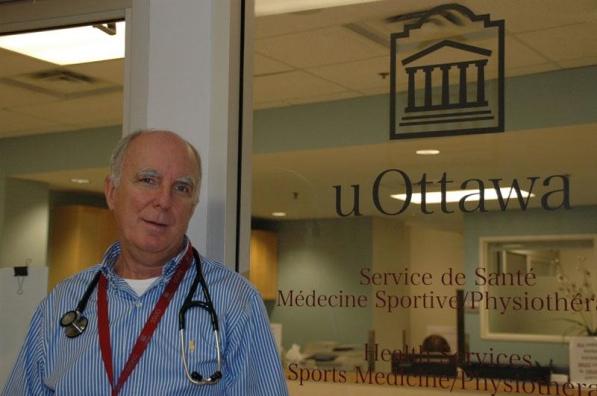

“[The prison medical system in Canada] is grossly inadequate,” says Dr Don Kilby, director of health services at the University of Ottawa, adding that larger, more private spaces are needed to reduce the risk of diagnoses being revealed.

Kilby says that even though the rate of HIV transmission in prison is 20 times greater than the streets, from a combination of drug use and unprotected sex, the stigma is also greater.

“Within [the prison community], people are often less informed and more prejudiced,” says Kilby.

Kilby says he often sees poz inmates with guards present, wearing orange jumpsuits and shackles. He says this can be deemed as humiliating, but the argument is a matter of individual rights versus societal rights.

“Prisoners do have the right to accept treatment. But they’re likely going to be put into embarrassing situations because they don’t have privacy,” says Kilby.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra