In a meeting with Malawi at next month’s G20 summit, Prime Minister Stephen Harper plans to raise the issue of a queer couple jailed in that country, but opposition MPs say it’s a “minimum” response to addressing international queer rights abuses.

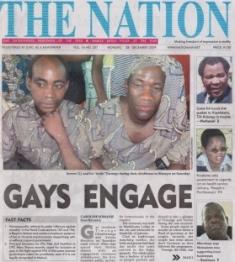

On May 20, a judge in Malawi sentenced Steven Monjeza and Tiwonge Chimbalanga to 14 years in prison with hard labour. The two were arrested in December 2009 after they held a symbolic engagement ceremony. Monjeza and Chimbalanga were convicted of “unnatural acts” and “gross indecency.”

Last Friday, the prime minister’s spokesman, Dimitri Soudas, told La Press that Harper would raise the issue with Malawi’s leadership at the G20 conference in Toronto this June, if not sooner.

“It’s a situation that we don’t find acceptable, and the prime minister does plan on raising it,” a PMO spokesperson confirmed with Xtra.

Malawi will be attending the G20 because of their position in the African Union, and Harper has made maternal and child health in the developing world a focus on the G8 and G20 meetings.

For some opposition critics, simply raising the plight of the Malawi couple at the G20 doesn’t go far enough.

“This level of discrimination — the criminalization of sexual activities between consenting adults — is really appallingly oppressive,” says Liberal foreign affairs critic Bob Rae. “It just takes us right back to the darkest of times, and I think it has to become a stronger priority for Canadian foreign policy generally.”

NDP MP Bill Siksay, the party’s queer issues critic, says the G20 meeting is “a very important start.” Siksay hopes that if Harper takes the initiative on Malawi, other world leaders may be encouraged to speak up.

Paul Dewar, the NDP’s foreign affairs critic, says he’s glad to hear that Harper will address the issue with Malawi, but he adds that the meeting is “a minimum.”

“It’s a matter of what is the message,” says Dewar. “I would like to have a strong engagement on the issue, including having people from our country, who represent our country, being in Malawi to talk about what our values are, and how we deal with things here in a relational aspect.”

Rae sees the issue in the context of a larger trend around the world. He notes the Ugandan anti-gay bill and an ongoing trial in Malaysia, where the country’s former deputy prime minister is facing charges of sodomy.

“We’ve got several areas and issues where there’s clearly serious, serious problems of human rights and respect for freedom and dignity,” Rae says. “In light of that, it’s kind of surprising that the prime minister would have invited Malawi to be part of the discussion, but now that he’s done that and Malawi’s coming, the prime minister has no choice.

“He has an obligation now to talk to them about the implications of that, and how serious it is for human rights and for the appalling treatment of those two individuals.”

Rae’s ultimate desire is to make queer rights a priority in Canadian foreign policy.

“I think we have to understand that, as Canadians, having taken such an advanced position ourselves with respect to recognizing gay relationships and gay marriages, that it would be a wonderful thing if we could champion this as a priority for our foreign policy,” Rae says.

In 2008-2009, Canada spent more than $25 million in development money in Malawi, but the Canadian International Development Agency has nothing listed on its website for Malawi in 2009-2010. Malawi is not one of CIDA’s “countries of focus,” and therefore no longer receives priority aid funding.

Dewar believes this weakens Canada’s ability to deliver messages for queer rights in countries like Malawi.

“It leaves us with less of a bully pulpit, if you will,” Dewar says. “Less of a stage to convince and engage, and that’s what a lot of people, myself included, were concerned with. As you withdraw from a region or area of the world, by design you have less influence. So absolutely, one of the outcomes of withdrawing from Malawi and other countries is that it means that we’re just not there on this issue and many others.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra