Canadian director Sharon Lewis says her latest documentary is “a love letter to God.” It’s an apt description: With Wonder follows eight queer people of colour and their evolving, sometimes strained, but always hopeful, relationships with God. Their stories take place across cities like Montego Bay, Los Angeles and Lagos, but all are connected by their faith, and Lewis’ poignant portrayal of their queerness.

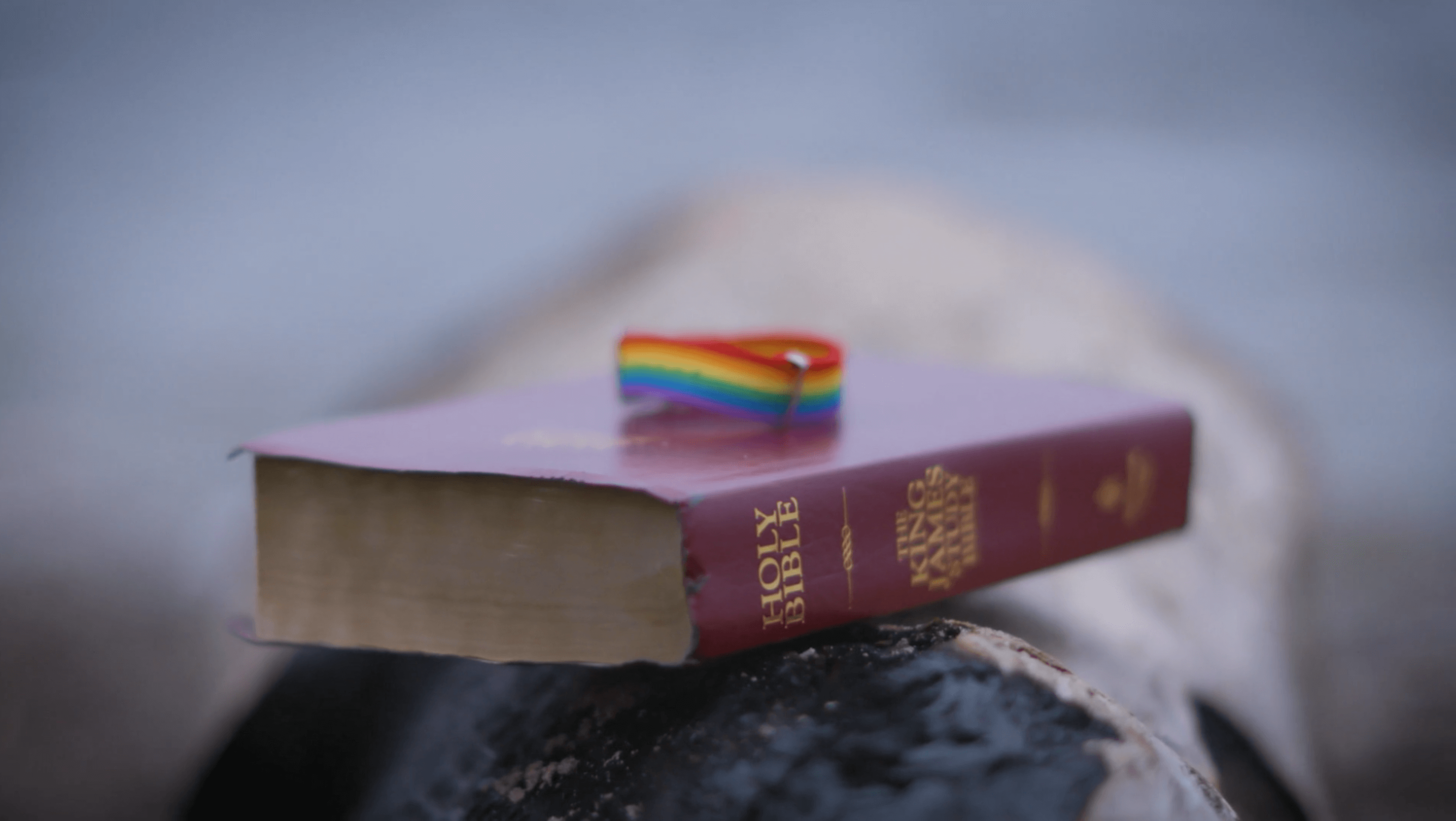

Credit: Courtesy of Sharon Lewis

Faith, spirituality and queerness, however, aren’t always so straightforward—especially not for Lewis. “I wouldn’t consider myself a religious person,” she tells Xtra. “It wasn’t until I started doing the doc that I was like, ‘Oh, I think I might be a closeted Christian.’”

Xtra contributor Ashleigh-Rae Thomas was raised in a conservative, Christian, Jamaican home before moving to Canada and realizing she was queer. She struggled with her faith in the same way the documentary’s Jamaican participants Maurice Tomlinson, Jessycka and Phyll do. Though she’s since realized she’s agnostic, Thomas has always wondered what her life would have been like if she remained religious.

Thomas and Lewis sat down together (virtually) to share an intimate conversation about the film, growing up with religion, Blackness and queerness and finding a balance between identities.

Ashleigh-Rae Thomas: Religion definitely feels very colonial to me. I feel like I would have been a religious person if I was allowed to choose at a more educated age as opposed to getting taken to Kingdom Hall and having it forced on me, and then me asking questions and being told, “It’s God’s plan. It’s God’s plan. Don’t ask questions.” I think I would have come to religion myself, if I had been allowed.

Sharon Lewis: Is there any part of the doc that you found hard to watch?

Thomas: When Serena [a Chinese-American lesbian, and daughter of a preacher] said her parents had never met her partner, that hit close to home for me. My mom is a little bit more lenient than my dad, so she has met my partner. She actually took us out: we all watched a baseball game together, and that was monumental. But my dad is like, “Do not bring that in my house. I don’t want to talk about it. I don’t want to hear about it.” So, Serena’s part, especially her journey as a mother, was hard to see, because I would like to have kids one day. Her journey as a mother with her mom being like, “My parents kind of came around just to see their grandchild.” My mom has said to me, she’s like, “I would be in your grandchild’s life because it’s the situation, not their fault.” And I was like, “That’s kind of an awful way to put it.”

What led you to create the documentary?

Lewis: I had made a documentary for CBC on the first openly gay Black classical music conductor, Disrupter Conductor. And when I met Daniel, he started talking about how religious he is, and how much he grew up in the Christian community. For some reason in my head, it felt like I could only be queer and secular. I had not really met anybody who was able to be queer and Christian.

We started talking about conversion [practices]—the doc was going to be about conversion so-called “therapy.” I started interviewing people around conversion practices, and it seemed to me that the essential question at the bottom of all of this, that the people I was interviewing were struggling with was, “Can you be queer and Christian at the same time?” Because, if you believed you could be both, then conversion practices wouldn’t speak to you.

When I talked to [Jamaican activist] Maurice Tomlinson and he told me he was going down to the Montego Bay Pride, I was like, I need to follow him, I have to go to Jamaica. I’m half Jamaican and half Trini, and I don’t think I’ve ever been fully out to my family. I present as straight, and my partner is male; I have a certain amount of privilege and invisibility. And I thought that this documentary would allow me to really explore and come out in a way again.

Thomas: I was wondering why conversion practices weren’t really talked about in the documentary. But at the same time, I was glad they weren’t, because the documentary has such a hopeful tone.

It reminded me of when I came out to my mother, she brought me to a “Christian counsellor.” It wasn’t until I was older that I realized she was a conversion so-called therapist. And I remember saying to the woman, “Did you print your degree off Google Images? What kind of psychiatrist are you? You’re horrible at this, you can’t bring religion into therapy.”

“This film wasn’t for white people and it wasn’t for straight people. It really was for us. To us.”

Lewis: I’m glad you’re saying that, because I really struggled with it. In 2018 in Hollywood, I was seeing those movies about conversion practices. And there was the documentary about conversion so-called therapy, where white people were taken into a camp. And I felt that’s not how it happens in our community. It’s not like we were forced to go up Christian camp or whatever; the way it happens is the local priest sits you down and talks to you and basically tries to convert you. And I thought, that’s a much more insidious way that it happens in our communities. And we don’t necessarily call it conversion therapy. So, I didn’t want to put a white label onto it. I wanted this really to feel like our community, and this is how it happens in our community.

Thomas: You captured that well.

Lewis: When you talk about your parents trying to convert you, or the local priest trying to tell you, it doesn’t look like how it does for white people. And this film wasn’t for white people and it wasn’t for straight people. It really was for us. To us.

I got to a certain point in the doc, probably a year into it, where both myself and the editor said, “The BIPOC experience is so specific, especially when you’re talking about a colonial religion, that I want to just focus on that.”

Thomas: I’m glad that that’s the route you chose to go down. It was very refreshing seeing people who look like me and sound like me.

Moving away from the documentary, how would you describe your relationship to Christianity or to God?

Lewis: I think in the same way my queerness could be invisible, my connection to Christianity can be invisible because I don’t believe that Jesus is the only way and is the only salvation, and I don’t believe being a Christian is the only way to feel the love of God. But what I do believe in is many of the Christian principles. Maurice says it best when he says that the Jesus he knows is of the margins and for the margins. And I really, really love that—Jesus was a rebel and an outsider, and worked on the margins and worked for the people on the margins. That’s the essence of Christianity. That’s the part that I connect to.

I still have a hard time calling myself a Christian. I don’t know if I even have an easy time saying I’m queer. But “Christian” is filled with so much colonial oppression, and the idea that Jesus is the Saviour—I still struggle with it. This documentary is helping me to kind of come to terms with my love of God and my love of Christian teaching without the homophobia and colonialism.

“You don’t have to choose between being queer and the love of God.”

Thomas: Did you ever notice a rift between your queerness and your spirituality as others did in the film?

Lewis: That didn’t occur to me because of the climate that I came out in, in the ’90s. I was doing a lot of activism work and a lot of AIDS activism work, which was very secular. And to be queer meant to be secular. I didn’t know that I could have both. And unfortunately, that meant giving up part of my culture, which is going to a Black church, which is going to a clap hand church, which is going to the churches in rural Jamaica—all of which feels integral to part of who I am. With Wonder has been a journey for me to kind of heal those sides of myself and bring them together.

Thomas: What would you tell a young, queer Christian who’s just coming into their identity?

Lewis: You don’t have to choose between being queer and the love of God. And I think that’s what affected me the most when I interviewed the participants: the anguish and the loss of love and connection to a higher self that kept them safe. The very thing that kept them safe, that kept them connected and guided them felt like it was being taken away from them.

Thomas: That was the note that I got from it as well. I think you really did accomplish that. What would you like to have known on your journey with spirituality and self-acceptance? What would you tell your younger self?

Lewis: I would say now: my God is funny, fierce and I have more than one. I have a couple. When I think about my higher power, I think of [Black Panther’s] Okoye: warrior, fierce, gorgeous, beautiful. And then sometimes I have to call on Thanos from Marvel, because I need somebody who’s a destroyer, somebody who’s fierce and not scared. So, I have a pantheon of gods that I call on.

Thomas: A lot of religions have a pantheon. So that’s valid.

Lewis: I don’t believe that Christianity means that I don’t have access to those.

Thomas: A lot of times, I feel like documentaries leave me feeling helpless. With With Wonder, this was not the case at all—it left me feeling like [the participants] have God in their hearts and they’re happy. What’s so different from my situation and theirs? And I mean that in a hopeful way, instead of a helpless way.

Lewis: It’s really what I wanted. You know, it’s funny, I just read a review from this white male reviewer. And he was like, “I don’t get it. Why are they still choosing the church?” And I was like, “Oh, my God, this is exactly what I’m talking about.” Stop shaming them. You have no idea what it’s like, you know, as a white man, why religion may be so important. When you’re growing up in a small place, and the central place that you go to get community support is your local church, it infuses every part of your life. It is not something you only do on Sundays.

“It’s a love letter that they have found a space in their life to be queer and to love God.”

Thomas: I went to a Christian school in Montego Bay—so even more Christian than public schools are—because everything in Jamaica is religious. It’s not like here where you have separation of church and state. So, to go to a Christian school was like, two times the religion. Everything revolved around religion and it was often used as a tool to shame. People who didn’t grow up in that environment will never understand that. They will always be like, “Why did you choose to be religious? Look at what religion has done.”

Lewis: Exactly. There’s a quote that Serena says: “Shame didn’t come from God, shame came from other people.”

Thomas: Why did you describe the film as “a love letter to God?”

Lewis: Because I think that ultimately, all of the eight participants find a way to feel connected to and love God and they have forgiven the idea of a God that is judgmental and threatening to them. It’s a love letter that they have found a space in their life to be queer and to love God and that doesn’t mean they accepted the church and religion. My hope as a filmmaker was that when you watch this film that you would feel that spirit of love.

This conversation was edited for length and clarity.

With Wonder shows at the Reelworld Festival until Oct. 27. (Digital screenings are geoblocked to Ontario only.) For more info on the film, visit its official website.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra