It seemed unthinkable just two months ago, but the New Democratic Party tripled its seats Monday night, garnering more than 100 — the party’s best showing in history. A party that won just 8.5 percent of the popular vote in 2000 captured more than 30 percent on May 2.

To understand the game-changing performance of the NDP, we have to go back five years.

In September 2006, the New Democratic Party faithful met at a hotel for their semi-annual policy conference. Such conferences usually yoke mild political celebrity worship to Robert’s Rules of Order–style wonkiness. Earnest, hours-long policy meetings are broken up by barnburner speeches. The meetings are dry but, in a puritan way, affirming.

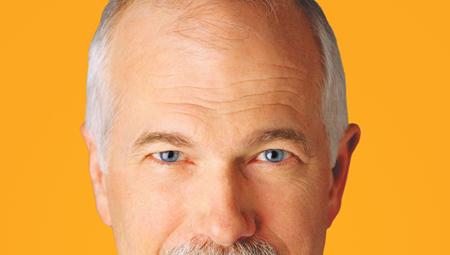

The NDP’s 2006 conference was different for several reasons, and, prophetically, it foreshadowed what was to come. Already, Jack Layton’s name and face were appearing on NDP branding more prominently than the party’s name. Already, the focus was shifting from grandiose new programs to so-called pocket-book issues. And, perhaps most importantly, the conference was held in Quebec City, in the heart of a province that would lead public opinion in the 2011 election.

At the time, there were no NDP MPs in Quebec.

Even before the conference started, it threatened to go off the rails. The grassroots of the party was planning to pass a resolution calling for the immediate withdrawal of Canadian troops from Afghanistan. As Corvin Russell, a onetime NDP member and journalist for Rabble, remembers it, it became clear that the voting delegates at the conference would favour — overwhelmingly — ending Canada’s war effort immediately. So, just weeks before the conference, Layton announced that he favoured withdrawal, saving face from potential embarrassment.

For those who think that the lefties are an undifferentiated mass, this is going to come as a surprise. But card-carrying NDP members — those eligible to attend conferences such as this one — are generally understood to be the left flank of the NDP, more lefty than either party brass or rank-and-file NDP voters.

“There’s always been division within the party between the left and the right wing. I’m sure outside of the party, it all looks left, but those divisions go back 20 years,” says Andrew Brett, who attended the Quebec City conference as an NDP delegate.

The inevitable tension was fought out for the last time in 2006, as the conference became a contest between the progressive membership and the more staid party machine.

Brett was part of the progressive youth and queer caucuses. During that convention, he fought to pass a resolution condemning the Conservatives’ plan to raise the age of consent, but he was foiled by vote stacking from party brass, especially Windsor MP Joe Comartin.

“They were afraid of being attacked as soft on crime,” he says. “But even the MPs who opposed us, they argued on a technicality.”

Comartin won the day, and — after stacking a committee — the motion was tabled. At the time, Brett bitterly condemned Comartin and other NDP leaders for it. Now, he is more sanguine.

“It was intense and divisive, but it was all very exciting,” he remembers.

Even so, the NDP’s Quebec City conference was historic for several reasons. Putting aside its aspirational location in la belle province, there’s still the matter of what happened to the NDP’s leftwing policies at the conference. Some were defeated. Others passed but were simply not implemented. Others, like Brett’s age-of-consent resolution, were sent to a kind of procedural no-man’s land.

The consent resolution did rear its head one final time. After the conference, it was quietly passed as a recommendation at the NDP’s federal council. The federal council’s recommendation, however, was ignored by Layton and his caucus in the House of Commons.

Subsequently, the influence of the progressive wing of the NDP — and its conference delegates — waned. The conferences that followed have been mild in comparison, and some progressives, like Russell and Brett, have simply moved on.

In the House of Commons, the shift has been pronounced. Rather than oppose the Conservatives’ three-strikes sentencing bill — as once it might have done — the NDP, led by Comartin, by then the NDP’s justice critic, helped amend it. Then, he and his party helped pass it.

Or take the Conservatives’ so-called human-trafficking bill, introduced in the last Parliament. It was the kind of bill with big, logical holes in it — and the whiff of xenophobia, misogyny and the fear of sex. Once upon a time, it might have been the kind of bill the NDP fought a noble, losing battle to educate Canadians about.

Not so after the Quebec conference.

While a rump of MPs voted against it — BC MPs Libby Davies and Bill Siksay, plus Halifax’s Megan Leslie — the rest of caucus supported it.

In this way, it echoes the consent bill, which was opposed by just one MP, Siksay. In fact, even though Siksay’s position was widely shared at the Quebec conference (before the bill was yanked from the agenda) and later endorsed by the party’s federal council, Siksay was disciplined for his vote. Given this, it’s no surprise that Siksay’s parting wish for his party is for it to begin to oppose the Conservatives’ crime agenda.

“A lot of those issues made me really uncomfortable,” says NDP member Susan Gapka, one of the party’s national lesbian, gay, bi and trans reps. “Supporting those bills didn’t seem like it was consistent with our values.”

Gapka, for her part, chalks up the NDP’s support to debt — neither the NDP nor the Liberals could comfortably oppose the Conservatives’ crime agenda until they’d paid off their debts from the 2008 election.

That may well be true. But even so, the Quebec conference and the NDP’s subsequent voting record represent a move away from principled fights that are unwinnable and toward more of a middle way.

Ian Capstick, a political commentator and former Layton aide, places the NDP’s push to the middle a couple of years earlier — in 2003 — when, as he says, the party stopped talking about the “idea that Layton would pull Canada out of NATO and NORAD or would run perpetual deficits.”

As for the mainstream media, they’ve been pretty good at reporting on the NDP’s platform and performance during the campaign, says Capstick.

But what they’ve missed is the history. And they’ve been poorly placed to get it right, having spent a long time trying to understand the Liberal and Conservative party machines and virtually no time — until this past month — trying to get inside the head of the NDP.

The result during the campaign was some painfully shallow analysis. The NDP surge was attributed to Layton’s personal charm, his performance in the televised leaders’ debates, his French accent, his modest chat on Tout Le Monde en Parle and even to a single cheer for the Montreal Canadiens caught on tape.

No one I spoke to — including Brett, Russell and Capstick — was willing to dismiss Layton’s charisma. Some dippers stress that Layton’s charisma is especially pronounced compared to the relatively unlikeable stiffs who are his main rivals.

And, of course, it doesn’t hurt that Stephen Harper and Michael Ignatieff have spent a good deal of time and money ruining each others’ reputations. Their personal attacks were a boon for Layton. The result, personality wise, was a perfect recipe for NDP gains.

Sort of. It’s more like a decade-long overnight success story, or, as Capstick says, “six years of Layton preparing and tilling the ground.” That’s included investing heavily to win ridings in places where they weren’t previously competitive, from Linda Duncan’s in Alberta to Jack Harris’s in Newfoundland, Capstick says, which has a spillover effect.

But it wouldn’t have mattered if the party was talking about withdrawing from NORAD or nationalizing the telecoms. Instead, it has been pushing sleek, middle-of-the-road, affordable policies designed to alienate as few people as possible.

Put another way, “the NDP haven’t given the media a lot to attack them on,” Russell says.

Wedge issues like sex work, harm reduction and marijuana — issues that matter to party volunteers like Gapka — were all but invisible during the campaign. Instead, Layton stressed feel-good promises over tougher sells and avoided anything that would have branded him and his party as ideological.

So how does that bode for the party, now that the election is over?

“It’s too early to say,” says Russell. “[But] nobody campaigns to the right and governs from the left, so that’s not going to happen.”

Even so, a new, relatively inexperienced caucus of true believers will certainly make it more difficult for Layton, Comartin and his ilk to keep the progressive side of the party in check. And, as Brett points out, parties that gain seats in Quebec tend to shift to the left. Add to that a progressive membership, made up of people like Gapka, and that pressure becomes harder to ignore. Such a shift is possible, but any bold move could jeopardize the NDP’s popularity.

On the other hand, moving toward the centre — either because they form a coalition with the Liberals or because they want to further poach voters from that party during the next election — would be just as difficult.

“I don’t think that they can move any farther to the right without losing their base,” Russell says.

That means they’ll be walking a high-stakes tightrope in the coming months. And, given the sudden surge of media attention, the whole country will be watching this phase of the NDP’s development a whole lot more closely than the last one.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra