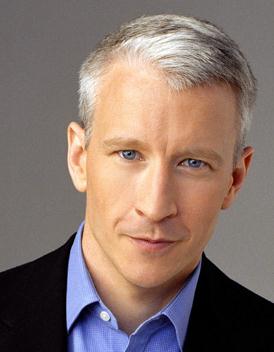

Facebook and Twitter lit up with the recent news that CNN personality and journalist Anderson Cooper would be receiving an award at this year’s GLAAD Awards on March 16.

For his coverage of queer-related subjects, Cooper has already been nominated for various GLAAD awards on seven occasions, winning three times.

Most people seemed to be elated that Cooper, son of celebrated designer Gloria Vanderbilt, would be winning this coveted award. But while I’ve enjoyed and appreciated a good deal of Cooper’s reporting, something did feel odd about this particular award. It is, after all, the Vito Russo Award, named in honour of one of GLAAD’s founders, the author of the landmark book on cinema’s longstanding issues with homosexuality, The Celluloid Closet.

Perhaps people have forgotten, but I haven’t. I heard Russo lecture in New York City, when he talked his way through a series of clips of Hollywood films. I also interviewed him about a year before he died of AIDS, for an undergraduate course I was taking, one of the first offered in Canada about homosexuality and cinematic representation. If there was one thing Russo railed against, in no ambiguous terms, it was people who remained in the closet. He argued, passionately and repeatedly, that the people he was most angry with and disappointed in were not the straight homophobes (“I already knew we couldn’t count on them,” he’d say), but rather the lesbian and gay people in positions of power who remained closeted. “They create the sense that to admit to being gay is something so terribly shameful it must remain hidden,” he said.

Timing is everything, and by odd coincidence, this past year marked the roundabout coming out of both Cooper and Oscar-winning actress Jodie Foster. Cooper came out officially through an email to his friend Andrew Sullivan, who wrote about it on the site The Daily Beast. Foster came out in a now-famous cryptic speech she made while accepting a Golden Globe Award. The only thing stranger than her speech was her choice of dinner guest — that being Mel Gibson, who sat, looking aghast, as she talked about the news about her being a lesbian as old hat.

Which it was, in a sense. If Cooper and Foster have indicated anything, it’s how much things have changed since Russo died of AIDS-related causes in 1990. In a sense, it’s like coming out by osmosis. Just let the rumours fly, let various people discuss it and speculate, until it becomes an accepted truth. In 2002, I interviewed Foster and asked her if she felt any special responsibility to the gay and lesbian community. “I feel a responsibility to many different causes,” she said, after a pause. She knew what I was getting at. I wrote at the time that her being lesbian was about as well kept a secret as William Shatner’s hair transplants.

Foster and Cooper have proven that there’s now no need for that tell-all Advocate interview of yesteryear. Your official coming out will still create something of a media spectacle, but less than it would have back then. In fact, both were sticking to a rule that was very old school: it was WH Auden who said he “would neither proclaim nor pretend.”

This becomes a complex issue in the case of Cooper, as many of his defenders have correctly pointed out. As a journalist, he has reported from parts of the world where homosexuality is still a criminal offence — like Egypt, for example, where Cooper reported throughout the Arab Spring uprising two years ago. But Foster’s rather late coming out has also been defended. It was a truth universally acknowledged in Hollywood that to be out would destroy an A-list actor’s career. If indeed Foster had come out 30 years ago, there can be little doubt her film career would have been remarkably different.

But Russo had little time for such arguments. He blasted people who remained closeted. He said things would change only if people stepped out and took risks. While I understand the importance of letting people come out on their own terms — and Russo was opposed to forcibly outing public figures — I also see Russo’s argument. If no one ever took a risk, and waited to protect their careers, then we wouldn’t have the rights we do today. It is precisely because so many came out so brazenly, often risking their own lives (remember Harvey Milk, among others) that we live in a world that has changed so remarkably on the queer-acceptance front.

I’m not opposed to GLAAD giving Cooper an award. Or Foster, for that matter. But named after Vito Russo? That makes me just a bit queasy. Memo to GLAAD: why not call it the Better Late Than Never Award instead?

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra