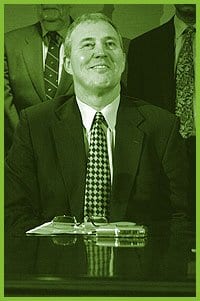

On the morning of Apr 6, just after being appointed chief of police by the Toronto Police Services Board, Bill Blair stopped by city councillor Kyle Rae’s office. Rae exuberantly kissed Blair in congratulations. Blair, 50, didn’t flinch, but cheerfully told Rae that he was looking forward to being the first chief to officially attend Pride celebrations this year. (This week he said he’d hold a reception at police HQ during Pride.)

Rae and Blair go way back. When Rae was sued by some 52 Division officers in 2000 for saying that they acted like “rogues cops” on a “panty raid” when they raided the Pussy Palace in September of that year, Blair, then a senior officer and Julian Fantino’s right-hand man as staff superintendent in charge of the community support units, told Rae in private that the lawsuit was “bullshit” and that he was “angry and embarrassed” by it, Rae says now.

Blair represents a big change in style from the last chief. While Fantino was often brash and confrontational, Blair, an articulate charmer, is the type who quietly seeks consensus, as demonstrated by his interest in community policing. Fantino was always the simple-minded moralist; Blair is a more sophisticated pragmatist.

But Blair has had his ups and downs dealing with the lesbian and gay community in which he’s revealed something of how he operates.

In July 2000, Blair helped arrange a meeting in the chief’s office between Fantino, who had just been appointed chief that March, and a group of gay activists including Coalition For Lesbian And Gay Rights In Ontario (CLGRO) members Richard Hudler, Nick Mulé, Clarence Crossman, Christine Donald and myself. The motivation was to air concerns about Fantino’s handling of the infamous kiddie porn ring investigation in the early 1990s when Fantino was London’s chief. The investigation resulted in few convictions and no kiddie porn ring, except for the teenaged hustlers who police claim were victims.

When we arrived to find Blair alone in the chief’s boardroom, he immediately said, “We’ve been set up,” complaining that reporters had called him about the meeting as a result of a CLGRO news release. None of us activists had assumed the meeting was secret.

“Why do you feel the need to be public about this meeting?” Blair asked angrily.

Looking back, Mulé suggests Blair’s outburst was purposeful.

“I really believe this was a psychological tactic, an attempt to both disarm us and set the tone of the introduction of the meeting in such a way that it allowed Fantino to go on the offensive,” says Mulé.

Fantino arrived, claiming he felt betrayed. It was so tense, several members of our delegation thought we had no option but to leave. Donald saved the day by calmly suggesting that we all step back and talk since we were already there. The meeting went ahead, after all, with the delegation suggesting that the kiddie porn investigation was an antigay witchhunt.

While Fantino defended his actions, Blair, who of course had not been involved with the investigation, said nothing. But after the meeting Blair apologized to me for overreacting at the beginning and said that he hoped that the ghosts of the London cases would now be behind Fantino.

In the months following the meeting, Blair helped Fantino set up Toronto’s first Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender (LGBT) Police Liaison Committee, which is elected annually, and encouraged Fantino to appoint the first official police LGBT liaison officer (first Judy Nosworthy and now Jackie O’Keefe, both openly lesbian).

But, in fact, the liaison process almost didn’t happen because of the fallout from the Pussy Palace incident where male police officers stomped through a women-only bathhouse. It was Blair as the senior community support officer who tried to reopen a dialogue. He attended a Pussy Palace protest meeting in 2001 and started to engage in dialogue with organizers. This time, too, he went on the offensive, and at one point accused organizers of engineering the raid themselves for publicity. And again, he retracted his inflammatory statements and tried to build consensus.

In the end, the Toronto Police Services Board brokered a deal with organizers. Police agreed to pay $352,000 to designated charities and provide sensitivity training to all police officers. Fantino never apologized, though the five male officers involved in the raid did as part of the deal. Blair has yet to say anything publicly about the settlement.

Explaining why they picked Blair, board chair Pam McConnell said that Blair understands “Toronto’s diversity” and “is a strong advocate of community policing and is committed to civilian oversight.”

If Rae’s and McConnell’s faith in Blair is justified, then a good place for Blair to start is to finally apologize for the Pussy Palace raid and to promise such a thing will never happen again.

There are bound to be con-tinuing conflicts and problems between the queer community and the police. It remains to be seen whether Blair will lead with his personal charm or lead with tactics that put his critics on the defensive.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra