Though he’s credited as director, Jim Hubbard’s documentary United in Anger: A History of ACT UP is as collective an exercise as the radical AIDS activist group it profiles. Pieced together from thousands of hours of footage shot by dozens of activists over a 20-year span, the work would never have been possible were it not for the happy accident of consumer-grade video cameras entering the market at the same time as the AIDS crisis.

“People were shooting constantly at our events,” Hubbard says. “It seemed like everyone had a camera tucked in their backpack on the way to the demonstrations. This was the first phase of the gay rights movement to be documented like this, and people would make copies of the tapes and send them around the country. In a way, the cameras became extensions of ourselves.”

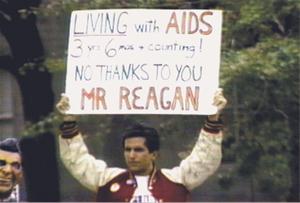

Covering ACT UP’s major interventions at places such as New York City Hall, the Food and Drug Administration, and the National Institute of Health, United in Anger captures the rage of those fighting, literally, for their lives. Whether showing activists chained together in the streets, soaked with fake blood, or being dragged away in handcuffs by the police, the film unflinchingly charts the battle for the benefits many HIV-positive people enjoy today.

Though the organization’s work is so thoroughly documented, this history hasn’t been consistently passed down. Mention ACT UP to the average 20-something gay person and you may well be greeted with a blank stare.

“That’s a huge part of why I felt compelled to make this,” Hubbard says. “It’s important to ensure this history isn’t lost to the next generation. But it’s also our intention to force the history of ACT UP into mainstream historical circles.”

So what is the history of ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Release Power)? Beginning with weekly meetings at New York City’s Lesbian and Gay Community Center (they hadn’t added Bi and Trans to the moniker yet), the organization expanded organically to include more than 100 groups with various causes in different cities. Bringing together activists from beyond the gay community — sex workers, intravenous drug users, the homeless and the women’s health movement — the group’s diversity was its strength.

“Women were a hugely important part of the movement,” Hubbard says. “They were the ones who had most of the political and organizational experience, because they were already working on issues like reproductive rights. They gave us lessons in civil disobedience and taught us the tactics the police would use against us. ”

ACT UP’s diversity was a product of the disease; “AIDS doesn’t discriminate” was one of its mantras and its membership was proof. People who would never have been activists suddenly found themselves in the streets fighting alongside people they would never have met, were it not for one fateful visit to the doctor’s office.

“In a certain way, AIDS destroyed the closet,” Hubbard says. “Before that you could succeed in the larger world if you kept your sexuality private. After AIDS, that was not a choice everyone was able to make. It utterly changed the way people perceived gays, because suddenly a lot of people were forced to come out.”

While AIDS united the gay community through shared tragedy and a common fight, Hubbard is concerned that’s begun to dissipate. Despite many advances being made, when it comes to HIV stigma he sees a backward drift.

“The idea back then was that all of us were living with it, whether or not we were individually infected,” he says. “You knew you could get it at any minute, so it was impossible to live in an us-versus-them world. We don’t have that same sense of community now, and there isn’t the same political focus.”

ACT UP’s politics weren’t just focused on relief for the sick. It was a pioneer when it came to sex education, distributing condoms and information publicly long before it was a common practice, another area where the gay community has lost ground as safer-sex fatigue grows.

“Sex is where you want to lose yourself, and in a way it’s antithetical to being careful,” Hubbard says. “I haven’t been fucked without a condom since 1984 and it still shocks me when I hear people are doing that. The only way it works is if you integrate it into your practice and it’s reinforced by the community. It’s something we all have to work on together.”

In the video interview below, co-director Sarah Schulman speaks with Elvira Kurt about making the film.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra