Shouts of jubilation and recrimination erupted in Uganda’s Constitutional Court Aug 1 as judges struck down the Anti-Homosexuality Act, ruling that parliament violated its own rules of procedure when it passed the act last December.

In declaring the anti-gay law “null and void,” the court found that parliamentary speaker Rebecca Kadaga abdicated her duty to ensure there was quorum when legislators voted on the bill. The court also ordered the government to reimburse half the legal fees of the nine petitioners who challenged the law in March.

The government now has 14 days to appeal the judgment to Uganda’s Supreme Court.

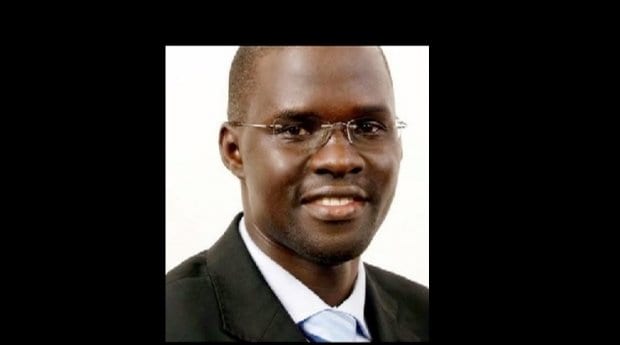

Lawyer Nicholas Opiyo, who co-represented the petitioners, tells Xtra the ruling is significant. The act cannot simply be reintroduced, he says. “They cannot simply resume from where the court said they were committing illegalities. They have to go back again, and it might be a long process, if that at all happens.”

Opiyo says cases involving people who are being investigated, or who have already been arrested and charged under the now-void Anti-Homosexuality Act, will have to be dropped, because “the basis for them has now been pulled away.”

The act had also been leveraged to suspend the activities of organizations like Makerere University’s Walter Reed Project, which offers AIDS services to gay people in the Ugandan capital of Kampala. A government spokesperson had alleged the project was “training youths in homosexuality.” The court’s ruling means such organizations will be allowed to resume operations, Opiyo suggests.

“But that said, we must be cognizant of the fact that the bigger problem still persists, and that problem is the sense of hatred, the sense of homophobia that has been planted by the Pentecostal movement in the process of enacting this law,” he says. “They will not relent. They will go all over the country; they will go back to churches and whip this issue of discrimination.”

Opiyo predicts a spike in the discussion against homosexuality in Uganda. “Every Sunday, when pastors and priests take to the pulpit, they pound this point,” he says. This pervasive anti-gay sentiment must be addressed once the celebration over the ruling ends, he says. “We must reflect on those issues as a long-term response to homophobia in this country.”

Opiyo thinks the court ruling might put pressure on President Yoweri Museveni, but he doesn’t think it will affect Museveni’s chances of reelection.

Opiyo is not surprised that the court ruled in favour of the petitioners — their case was strong on both the quorum (which the ruling focused on) and human rights questions, he says. What did surprise him was the speed with which the case was decided. He says he and his colleagues had been writing constantly to the court over a three-and-a-half-month period asking that the case be heard quickly.

Opiyo describes the atmosphere in court over the last two days as tense. “The pastors in their official priestly attire were all over the court, making their presence felt,” he says, “but also on the other side, you had members of the LGBTI community, who have been in hiding for fear of their safety. They were right inside that courthouse, so anything could have happened,” he says, adding it “was almost acrimonious.”

Following the ruling, members of the public hurled verbal abuse at jubilant LGBT community members, who had their rainbow flags snatched by police, but there were no arrests.

In addition to challenging the lack of quorum in the act’s passage, the petition filed in the Constitutional Court says the Anti-Homosexuality Act, “in defining and criminalising consensual same sex/gender sexual activity among adults in private, [is] in contravention of the right to equality before the law without any discrimination and the right to privacy” guaranteed under the Ugandan constitution.

It also states that the law’s criminalization of “touching by persons of the same sex” creates an offence that is “overly broad,” also a violation of the constitution.

The petition adds that the act, “in imposing a maximum life sentence for homosexuality, provides for a disproportionate punishment for the offence in contravention of the right to equality and freedom from cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment,” which is guaranteed under the constitution.

The petition challenged the act for targeting homosexuals with HIV, subjecting them to compulsory HIV tests and “classifying houses or rooms as brothels merely on the basis of occupation by homosexuals.”

The petitioners argued that the spirit of the act promoted and encouraged a “culture of hatred” in contravention of the right to dignity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra