TRUDEAU'S SENSE OF MISCHIEF. 'He liked to walk into the Commons and everybody gasped because he was wearing sandals,' says Trudeau's executive assistant Tim Porteous. Given Trudeau's penchant for wearing fur coats and even for taking ballet classes, he was often assumed to be gay. 'People talked about that all the time,' says Porteous. 'That was part of his Credit: Doug Ball

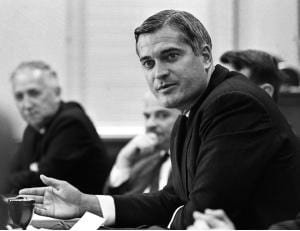

THE RELUCTANT SHEPHERD. When John Turner (right) stepped into Pierre Trudeau's role as justice minister in 1968, he inherited Trudeau's omnibus bill and the responsibility of getting it passed in the House of Commons. Not an easy task, particularly since Turner himself was less than keen to decriminalize gay sex. 'There is nothing in the bill which would con Credit: Chuck Mitchell

TAKING THE LEAD. 'I needed first of all to persuade my Cabinet colleagues that it was appropriate to put these controversial subjects on the order paper in the Commons. Several of them objected strenuously, some for political reasons, some for moral ones. But I held my ground until finally, tired of arguing, even the opponents ended up saying, 'If you want t Credit: Chuck Mitchell

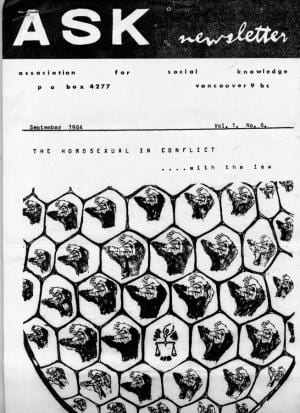

LAYING THE FOUNDATION FOR CHANGE. Without the Klippert verdict, without the Wolfenden Report, without the grassroots discussions fostered by homophile organizations like Vancouver's Association for Social Knowledge (ASK) and the Canadian Council on Religion and the Homosexual, Trudeau could not have decriminalized gay sex when he did, says gay historian Gary Credit: BC Gay and Lesbian Archives

“It was the personal initiative of Mr Trudeau,” says Marc Lalonde of the bill that decriminalized gay sex in Canada 40 years ago this summer.

Lalonde worked with Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau for years, first as his principal secretary then in key cabinet positions. He remembers Bill C-150 well.

“If not for the initiative of Mr Trudeau,” gay sex would not have been decriminalized in 1969, Lalonde says.

Tim Porteous, Trudeau’s executive assistant, says the Criminal Code amendments both fit with his boss’ conception of a “just society” and suited his “sense of mischief.”

“He liked to provoke people,” Porteous says.

Trudeau’s bill was nothing if not provocative.

“It’s certainly the most extensive revision of the Criminal Code since the 1950s and, in terms of the subject matter it deals with, I feel that it has knocked down a lot of totems and over-ridden a lot of taboos,” then-justice minister Trudeau told a media scrum outside the House of Commons on Dec 21, 1967, after introducing his sweeping 72-page, 104-clause omnibus bill.

In its quest to modernize Canada’s Criminal Code and bring it in line with society’s evolving views of which acts should and should not be illegal, Bill C-195 (and its successor the now-famous Bill C-150) touched on a variety of matters, from homosexuality to abortion to gambling to gun control.

“It’s bringing the laws of the land up to contemporary society I think,” Trudeau told reporters. “Take this thing on homosexuality. I think the view we take here is that there’s no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation.

“I think that what’s done in private between adults doesn’t concern the Criminal Code,” he said.

“When it becomes public, this is a different matter, or when it relates to minors this is a different matter,” he added.

Though the bill dared to tread into many areas widely considered to be moral issues, none proved more contentious than its proposal to decriminalize gay sex.

If passed, the bill promised to amend the buggery and gross indecency sections of the Criminal Code to ensure that anal and oral sex between two consenting, adult gay men would no longer be a crime — as long as it took place in private and between participants aged 21 years or older.

The amendment’s limited scope did little to lessen the fierce debate and fear mongering in and around the House of Commons.

Trudeau would become prime minister mere months after introducing his omnibus bill, leaving the Liberals’ new justice minister, John Turner, to somewhat reluctantly reintroduce the bill in December 1968.

Turner, who declined numerous requests to be interviewed for this story, described Bill C-150 to the House as bearing Trudeau’s “indelible imprint.”

It was Trudeau “who had the courage to assemble it, to introduce it into parliament and to defend it across the land under the sharp scrutiny of a general election,” Turner told the House of Commons on Jan 23, 1969.

Turner argued that the Liberals’ sweeping electoral victory in 1968 meant the proposed omnibus bill had already “been tested by public opinion and received a popular mandate.”

He also maintained that “there is nothing in the bill which would condone homosexuality, promote it, endorse it, advertise it, popularize it in any way whatsoever.”

“All it does is recognize what those of us who support the bill recognize: that there are areas of private behaviour which, however repugnant, however immoral — if they do not directly involve public order should not properly be within the criminal law of Canada,” Turner told CBC Radio on Apr 20, 1969 as the bill continued to make its way through debates in the House.

“There are acts and situations in life which most of us would consider to be immoral that are not crimes,” he said. “Adultery is one, yet it is not a crime. Fornication is immoral, I suppose to most of us, yet it is not a crime. These are matters for private judgment, private behaviour, private morals, and the criminal law says these are not our concern.

“In the same way, acts between people who suffer under a sexual deviation — as long as it doesn’t involve the corruption of a minor, as long as it doesn’t involve force, as long as it is not done in public — if in fact it consists of adult, mature, private behaviour, however repugnant as I’ve said to most of us, these are matters for personal conscience and should not be in the public criminal domain,” Turner said.

“We are not for a moment conceding that homosexual acts are in any way to be equated to ordinary, normal acts of intercourse,” he reminded the House of Commons.

Despite a lengthy, heated debate, Bill C-150 passed in the House of Commons by a vote of 149 to 55 on May 14, 1969 — six weeks before the Stonewall riots launched the gay liberation movement in New York.

One hundred and nineteen Liberals, 18 New Democrats and 12 Conservatives, including leader Robert Stanfield, voted in favour of Bill C-150.

One Liberal broke ranks and voted against it, joining 11 of Réal Caouette’s conservative Créditistes from Quebec and 43 Conservatives.

It wasn’t enough to defeat the bill.

Bill C-150 went on to pass in the Senate and received Royal Assent on Aug 26, 1969.

Trudeau’s “indelible imprint” had become the new law of the land.

***

As bold as Trudeau’s initiative was, it did not spring forth from thin air.

The bill’s introduction followed several key developments in Canadian and British society, chief among them the Wolfenden Report.

Published in England in 1957, the Wolfenden Report “became the Bible for liberal regulatory sex reform” in Canada, says Gary Kinsman, author of The Regulation of Desire: Homo and Hetero Sexualities.

In fact, Kinsman says, many Members of Parliament (MPs) in Canada arguing in favour of Bill C-150 “were basically using the Wolfenden Report for their crib notes.”

The Wolfenden committee had been charged in 1954 with investigating the “nauseating subject” (as one member of the British House of Lords put it) of male homosexuality and prostitution in the post-war reassertion of heterosexual family values.

The committee was asked to find a more effective way to regulate “sexual deviance.” Its solution: to separate the public and private realms and use criminal law to preserve public order and decency, while allowing people to do whatever they want — however immoral — in private.

“There must be a realm of private morality and immorality that is in brief and crude terms not the law’s business,” the report said.

That said, the report did not condone homosexual behaviour and in fact expressed concern about the possible “menace to boys” that homosexual men allegedly posed. Hence the prohibition against any homosexual act involving anyone under the age of 21.

As for homosexuality in the public realm, that was to be dealt with severely, the committee said, urging police to vigilantly patrol “public” spaces such as bathrooms.

Armed with the Wolfenden Report, early homophile organizations like Vancouver’s Association for Social Knowledge (ASK) began suggesting that similar reforms might be possible in Canada.

In 1964, ASK tried to support a private member’s bill by maverick NDP MP Arnold Peters calling for the decriminalization of homosexual acts between two consenting adults in private.

Peters’ bill — egged on, according to Kinsman, by a gay civil servant in Ottawa named Gary Nichols — would have made homosexuality a crime only if it involved an adult “assaulting a young person.”

ASK wrote to Peters to request a copy of the bill but never got any response.

“The bill never reached the floor of the House of Commons but it did give ASK its first real encounter with law-reform activity and generated publicity for homosexual law reform,” Kinsman writes in The Regulation of Desire.

To some extent Peters’ bill “foreshadowed the ’69 Criminal Code reform,” Kinsman says.

Peters (who also sought to introduce a bill to legalize abortion) would go on to become involved in Nichols’ homophile Canadian Council on Religion and the Homosexual, a group of about three dozen people, including some mostly closeted gay civil servants, some mostly straight Anglican and Catholic clergy and a few doctors and psychiatrists.

“We believed that homosexuality was abnormal and that it was something in respect of which they could use help. I was joined by many people of the religious community who were aware that many people in the community faced this problem,” Peters later told the House of Commons as it debated Trudeau’s bill in 1969.

According to Kinsman, the short-lived Council held discussion groups and submitted a brief supporting Wolfenden-type law reform to the Ontario Select Committee on Youth before disbanding in 1967.

“These changing attitudes toward homosexuality and support for law reform within some of the churches — in interaction with homophile organizing — paralleled developments in the United States and England,” writes Kinsman. “Limited as they were, these shifts represented a general change in social institutions and helped lay the basis for law reform.”

Three years after Peters’ private member’s bill went nowhere, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled 3-2 that Everett George Klippert should remain incarcerated indefinitely as a “dangerous sexual offender” for having sex with other men.

Though the climate could hardly be described as gay-friendly, many Canadians disagreed with the Klippert ruling and the possibility of life imprisonment for consensual sex among adults.

Klippert, a mechanic’s assistant in the Northwest Territories, had pleaded guilty to four counts of “gross indecency” and was sentenced to three years in jail. While in jail, he was visited by two psychiatrists on behalf of the Crown who successfully sought to have him declared a “dangerous sexual offender.”

Ten years after Wolfenden, the Supreme Court’s decision essentially made every practicing homosexual liable to imprisonment for life.

There was a limited, but real, public outcry.

As Kinsman writes, “The controversial Everett George Klippert case played a central role in speeding up the process of reform, especially in getting the Wolfenden reform strategy taken up by government.”

The Supreme Court handed down its Klippert ruling on Nov 7, 1967.

Six weeks later, Trudeau introduced his omnibus bill.

***

When Trudeau stepped into the role of justice minister in 1967, he did so with the full awareness that a succession of minority governments (including the one of which he was then a member) had neglected several “thorny” issues.

“Proposed amendments had been gathering dust in the department’s files,” Trudeau wrote in his Memoirs. “I needed first of all to persuade my Cabinet colleagues that it was appropriate to put these controversial subjects on the order paper in the Commons. Several of them objected strenuously, some for political reasons, some for moral ones. But I held my ground until finally, tired of arguing, even the opponents ended up saying, ‘If you want to risk destroying yourself, it’s up to you.’ And I had carte blanche.”

Trudeau’s commitment to modernizing Canada’s Criminal Code stemmed from his belief that there is a clear distinction between sin and crime.

“What is considered sinful in one of the great religions to which citizens belong isn’t necessarily sinful in the others,” he wrote. “Criminal law therefore cannot be based on the notion of sin; it is crimes that it must define.”

For Trudeau, it was a matter of personal liberty — a basic principle.

Others did not share his perspective.

The bill touched off fierce debates in parliament, as MPs on both sides of the House expressed strong personal convictions on the issue of homosexuality — even when it only concerned consenting adults, which Trudeau pointed out “was the sole focus of the amendment.”

Trudeau was convinced, however, that the time had come to adapt the laws of the land to the circumstances of our time, and that the public would support him and his bill based on the argument that “the state has no place in the bedrooms of the nation.”

Porteous became executive assistant to and speechwriter for Trudeau after “most of the legislative manoeuvring [on Bill C-150] had already been done.”

Asked what he thinks motivated Trudeau to risk his career on such a contentious bill, Porteous points out that Trudeau drafted the bill as justice minister — before he had given any consideration to running for the Liberal leadership. He made the decision “without having to consider the impact on the possibility of his becoming prime minister.”

Trudeau may also have calculated that the support he would gain could offset any support he would lose, Porteous suggests.

“The consensus was there were a fair number of votes out there from people who felt that homosexuals were being badly dealt with. But there was also a large number of people against the whole thing. Trudeau ignored the possibility that these people would vote against him. But he also recognized that he had actually gained an important group of supporters by passing that legislation.”

In particular, Porteous mentions Trudeau’s awareness of homosexuals “working in professions that might be helpful to him — for example, in the broadcast business — who would be much more likely to support him because he’d been the author of that bill.”

Although “anybody who had political aspirations would have run in the opposite direction,” Porteous says, the amendments fit with Trudeau’s conception of the “just society.”

He “had the only reasonable contemporary attitude to homosexuality,” he says.

Trudeau also had “a sense of mischief,” Porteous notes. “He liked to walk into the Commons and everybody gasped because he was wearing sandals.”

Given Trudeau’s penchant for wearing fur coats and even for taking ballet classes, he was often assumed to be gay.

“People talked about that all the time,” Porteous says. “That was part of his provoking people. He did things which would encourage the people to believe that, and got enjoyment out of the fact that he was misleading them.”

Lalonde, who served as principal secretary to Trudeau before joining his cabinet, thinks the bill came about because the age of “flower power” was more permissive than prior eras. Plus the amendments suited Trudeau’s personal convictions, he says.

Homosexuality was “not particularly high on the priorities of the government of the day,” Lalonde notes.

But as justice minister Trudeau “was concerned with the fundamental rights of individuals” and Prime Minister Lester B Pearson supported him, Lalonde says.

Together, they managed to avoid radical opposition within the Liberal party, even though there was no great enthusiasm for the bill’s homosexuality and abortion measures in caucus. But nobody resigned and eventually cabinet endorsed the matter, Lalonde says.

“The government fully endorses this bill,” Turner told the House of Commons in January 1969. “It is a government bill, bears the government stamp and will be supported by the government.

“We feel bound to the bill as the principal item of social reform in this session of parliament. It is identified with our Prime Minister and party.

“We believe therefore that, on the one hand, we have the right and, on the other hand, the duty to stand behind the bill in all stages of debate that will follow,” Turner said.

There is no doubt, Lalonde says, that the omnibus bill “was a step toward personal liberty, for recognizing that the state does not need to legislate on private ethical issues.”

He credits Trudeau entirely for its introduction and passage.

“If not for the initiative of Mr Trudeau, it would have been years later” before such amendments were implemented, Lalonde says.

Kinsman isn’t so sure.

“It seems to me [that the situation was] much more complex,” he says. Trudeau doesn’t deserve all the credit; his way was paved by the variables and broader social trends that preceded the introduction of his omnibus bill.

Without the Klippert case, without the Wolfenden Report, without the grassroots discussions fostered by homophile organizations like ASK and the Council on Religion and the Homosexual, Trudeau could not have done what he did, Kinsman contends.

“Without all of these things, it would have been much more difficult for Trudeau to move at that time.”

Don McLeod agrees. “Trudeau was instrumental in getting it through but all of these things came into play too,” says the author of Lesbian and Gay Liberation in Canada.

Though some might argue that the homophile organizations had little direct connection to Bill C-150’s formulation, Kinsman maintains these groups helped shape the emerging discussion of homosexuality in legal, professional and religious circles that led to the bill’s introduction and passage. “Without them organizing, it would have taken longer.”

If anyone deserves credit for bravery, says Kinsman, it’s Peters, the maverick NDP MP who tried to decriminalize homosexuality three years before Trudeau brought his own bill forward.

“In 1964, for somebody to be raising that in parliament was pretty significant,” says Kinsman.

Peters introduced his private member’s bill three years before the discussions had begun to ripple through at least certain sectors of society, three years earlier in the social change movements of the 1960s, three years before the Klippert verdict angered at least some Canadians.

Peters “actually helped produce some of the discussions” that led to Trudeau’s bill, says Kinsman. Yet he’s often left out of gay history.

***

As Bill C-150 made its contentious way through the House of Commons, some suggested it be split so MPs could vote on each Criminal Code amendment separately. Trudeau wouldn’t hear of it.

He explained his inflexibility on this point on CBC Radio on Aug 14, 1968: “I can see nothing to be gained from having the same speeches — and they would be the same speeches — on 10 or 20 bills whether the Criminal Code should sanction opposition to sin or to public disorder.”

MPs will have “ample room” in the debates to dissociate themselves from those sections of the bill they find particularly “obnoxious,” Trudeau added.

McLeod believes that if the amendment decriminalizing gay sex had stood alone, it would not have passed.

“We would have had to wait until the 1970s or so. But since it was lumped in with lotteries, it passed,” he says.

Trudeau’s omnibus strategy, combined with party discipline and a majority government, ensured that the more controversial aspects of Bill C-150 would ultimately be adopted, although opposition members and the Edmonton Journal described the government’s process as “arrogant, authoritarian, undemocratic, brutal and downright immoral.”

The bill’s opponents in the House were outspoken and plentiful.

“If homosexuality were practiced on a widespread scale society would break down,” argued Walter C Carter (St John’s West). “If it were universally practiced, the human race in a matter of time would become extinct. Obviously, therefore, it cannot be said to be conducive to social progress….

“The bill gives legal recognition to a practice that is basically anti-social. If I voted for the bill, it would mean that I am condoning that which I feel if carried out on an unrestricted basis would destroy the way of life we have painfully built up over the centuries.”

Similarly, Roland Godin of Portneuf suggested that because “the adoption of the clause regarding homosexuality will help to reduce the number of births,” the government could speed up the process “of annihilating the Canadian nation… by moving an amendment promoting cannibalism.”

Godin and Gilbert Rondeau (Shefford) agreed that the ridiculous conclusion of proceeding down the decriminalization path would be to pass legislation legalizing marriage between homosexuals.

For Georges Valade (Sainte-Marie), carrying the amendment to its ultimate, ridiculous conclusion required asking how to reconcile “the fact that two persons can commit homosexual acts in private without being considered criminals, while three homosexuals performing the same acts in similar privacy would in point of fact become criminals.”

Steven E Paproski (Edmonton Centre) spoke about the dangers of “compulsive coercion.”

“Homosexuals proselytize,” Paproski claimed, “and in so doing endanger young people before they are at an age to realize what is involved. That is why in flashing a green light at this time the government is embarking on a course fraught with dangerous consequences.”

The Hon WG Dinsdale (Brandon-Souris) agreed with that particular worst-case scenario: “It is abnormal social behaviour, because homosexuals are predators…. Homosexuals prey on juveniles. It is something that spreads like a plague, for there is no more destructive drive than the sexual impulse running wild.”

Gérard Laprise (Abitibi) went even further: “A few years ago, one such sexual pervert assaulted boys who objected to such perversions and he killed them. He murdered them to satisfy his lust… Such sexual perverts are not satisfied with meeting other perverts; too often they try by every astute means available to pervert boys and sometimes, they kill or pervert. By legalizing homosexuality, such sexual perverts are given full liberty.”

Laprise also indicated that those under the legal age of 21 “who are sexually ill or perverted would resort to all sorts of tricks to take advantage of the provisions of the act.”

In a similar vein, Léonel Beaudoin (Richmond) said the passing of the amendment “would mean that young people would be continually threatened by the unbridled instincts of those sexual perverts.”

Other MPs were less concrete in their slippery slope arguments, asserting simply that the amendment was the first step toward decay, decadence and socialism.

The debate contained two other overriding themes: religion and illness.

On the former, Trudeau’s distinction between “sin” and “crime” failed to persuade all MPs.

“The only effect the proposed amend ment on homosexuality will have, if it is passed, will be to indicate that the government approves what God himself condemned so emphatically,” Laprise argued.

Former Prime Minister Diefenbaker, despite his reputation as a civil rights leader, indicated he was “sorry” to see this legislation: “We live in an age that is becoming more and more permissive. Some say there is no God, that each man should be able to live his own life as he wills as long as he does so in private. I do not find any support for that philosophy in the scriptures.”

In response, Stanley Knowles (Winnipeg North Centre) objected to “the constant appeal to religion as though some of the interpretations of religion which we have been given are the final answer….

“If true religion means anything it means compassion,” he said. “It means understanding, it means concern for people, especially people who are ill. That is the object of [this amendment].”

With respect to this “illness” theme, many MPs on both sides of the House referred to homosexuality as a disease and compared it at times to leprosy or tuberculosis in suggesting that a more appropriate legislative response was treatment.

Another common example was alcoholism. “Just as we worked for the alcoholics’ rehabilitation,” said André Fortin (Lotbinière), “we must try to rehabilitate the homosexuals since they have a disease, a sexual deviation.”

This compassion only extended so far, however.

As the Globe and Mail pointed out on Apr 18, 1969, “a number of MPs who have called homosexuality an illness, nevertheless have advocated its continuing to be treated as a crime.” Even those voting in favour of the amendments often offered only qualified support, referring to homosexual acts as odious or as “a sexual perversion which arouses a sense of horror in most normal people.”

Despite the backlash, Trudeau’s procedural tactics worked. Bill C-150 was adopted, although Trudeau himself was called a “dictator” in the process.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra