In 2017, after six terrible months of unemployed freelancing, I landed a job as a content strategist at a company that produced and sold medical aesthetic devices. These were sleek, silvery machines with futuristic touch screens and ergonomic wands that did everything from skin tightening, laser hair removal and intense pulsed light therapy, to vaginal rejuvenation and something called “skin resurfacing”—which involved dozens of tiny, energized needles that pierced the skin and encouraged collagen regeneration. I was 21 years old, far and away the youngest and gayest person in the office, and not yet openly transitioning. While still feigning cis to my coworkers, I would eventually begin hormone therapy midway through my time there, plus laser hair removal treatments whenever I could get them using the in-office machines—dodging questions with a shrug, saying, “I just like a really close shave!”

That job only lasted 10 months, but it was a foundational experience. I became intimately familiar with the varied and arcane options available to women to change themselves, albeit at a price. In ways both subtle and transformative, over a matter of months, you can alter your appearance—and, with it, your world—through a program of carefully administered, nonsurgical treatments. Feminization, by any other name.

At all times, we are inundated with messages communicating who and how we should be and look. We firm up wrinkles, fill in faces, shrink hips, build muscles, dye, grow, cut and shave our hair. The idea of natural beauty is something of a fiction, and rightfully so; if it wasn’t, there would be no need for gyms, tattoos or cosmetics. Everything is reversible or irreversible in its own way.

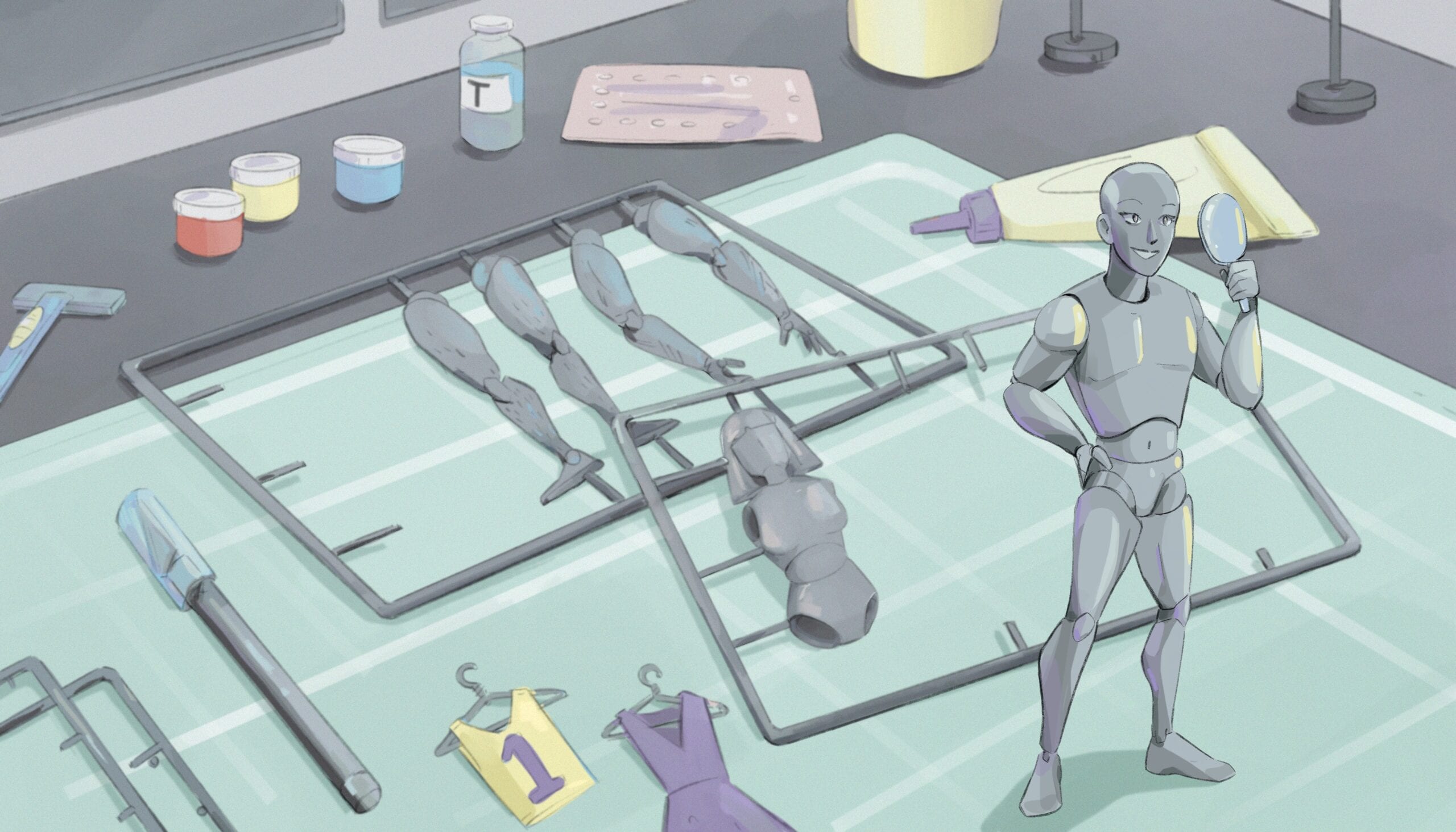

Transition is a universal experience. Some people want to imagine transness as uniquely pathological, but in truth, many cisgender people seek to change their bodies for similar reasons trans people seek to change ours: social perception, personal comfort, identity and community. Though these experiences are diverse, the essential logic is shared. Cis or trans, as human beings, our bodies are laboratories, experimental terrains, perpetual works in progress always in need of an adjustment.

It’s not only our external appearances. Your internal self—your personality, who you want to be and how you want to live in the world—is also a work in progress. Growing up, I wanted to be a veterinarian, then an English teacher, then a researcher; now I’m going to law school. I’ve been a hundred different people in my short lifetime, and I will surely be a hundred more. Everything I want and everything I am was once a phase, and one day it will be over. And that’s okay. We can’t know what our lives would or should become, because we cannot predict the future. Everything is subject to change; we are always, in some form, in transition.

Recognizing that everyone changes their bodies and appearances, and that these changes are deeply connected with their internal and social identities, I wonder why it is so aberrant, so outrageous, for trans and non-binary people to demand similar bodily autonomy? Our desires transition; we should be free to as well.

I am writing this about a week since my two-year tranniversary, marking two years of medical transition. I love the way I look and feel. I still experience dysphoria, but it’s been acquainted with another, newer feeling: Confidence. Something feels right in a way I can’t quite explain. I wouldn’t trade that feeling for anything.

Over the past few weeks, with my anniversary approaching, I’ve had several conversations with friends and strangers about their own transitions. “I’ve been considering it, but I just don’t know if this is right for me,” is a common refrain. I get it: As a non-binary person, my own journey down the road to quote-unquote “feminization” has been rocky and meandering. I wanted it, but I didn’t think I had earned it. Who was I to call myself trans? Who was I to insist upon myself—in my case, to live recklessly between butch womanhood and gay effeminacy and claim both experiences?

“Cis or trans, our bodies are laboratories, experimental terrains, perpetual works in progress always in need of an adjustment”

But here I am. The process worked. And it will continue to work, so long as I suspend my disbelief. Once I stopped worrying about what it “meant” to transition—whether it was “right,” or “fair” or if I was in any way “representative”—then the idea of actually living in this body became something joyful rather than anxious. I had to divest myself of a binarized, precipitous view of transition as a one-and-done event. In truth, transitioning is exactly that—a transition. It is a gradual, gentle movement, like honey dripping off a spoon. Everything comes with time.

When I first started transitioning, I was convinced that I had made a horrible mistake. Everything I saw and everything I did reinforced the seemingly endless gap between the person in the mirror and the imaginary woman at the other side of the endocrinological rainbow. I didn’t know what I wanted, and the experience was either moving way too slowly or way too quickly. The hormones gave me mood swings and breasts. I was horrified.

I stopped taking hormones after just three months, and didn’t touch them again for another six months. In that time, I allowed myself to be selfish. I thought about what I wanted from my life: What parts of my body did I love? What did I want to change? What made me feel sexy, confident or powerful, and what made me feel insecure? What kind of people did I want to date, and what kind of things did they find attractive? What kind of clothes did I want to wear, and how did I want them to fit? When I went to the corner store to buy flowers or a lighter, did I want the guy at the cash register to call me “miss” or “brother”? What could I compromise on, and what could I not do without?

There are some people for whom these answers come naturally; others can just fake it. I think most people fall into the latter category. Though it is certainly true that many trans people always identified as their genders, for many of us, our bodies and our self-identities have melted and solidified at various points over time. There is no generalizable narrative that applies to all trans people when it comes to transition, how we articulate our identities or how we relate to our bodies. As much as we are often required to explain ourselves or justify our experiences, everyone’s story is their own, and it is changing every day.

Rather than seeing this variation and flux as a sign of your identity’s inherent instability, or a symptom of transness as merely a “phase,” we ought to use it to give ourselves permission to fully embrace the complexity and strangeness of human embodiment. Transness, as American writer and critic Andrea Long Chu writes, is less about identity and more about desire. Instead of thinking about categories, think about goals: What do I want, and how can I get it?

This process and those questions have proved to be incredibly useful for me. When I started taking hormones again, I did so without worrying about whether or not I was “trans enough,” or if I had the chops to work my way up to an ideal of femininity that remained out of reach. Instead, I treated transitioning as exactly that: Transition. I am in a process of gradual change, a daily commitment to becoming myself. I can stop when I want to. I can start when I want to. This is my body, and these are my choices.

“As a culture, we still don’t quite know how to make sense of the desire to change your body or sex outside of the vocabulary of medicalized monstrosity”

There is a popular narrative among conservatives (and even some so-called progressives) that people are being “pressured” into transition. In fact, the truth is the exact opposite: On social media, in popular movies, in music and in school, transition is taboo—no one knows what it does or how it works, only that it is supposedly mutilating. Ask the average cis person about transitioning, and they will inevitably ask about “sex change” surgery, with a giggle or a grimace. Trans people are seen as scientific experiments, aberrations, freaks of nature, or else as bad drag performers, the butt of the joke of gender, lying to everyone by appropriating femininity or masculinity, trying to be something we could never truly be. These messages are everywhere, criticizing us pesky transsexuals or trans-trenders as faddish fakers or else stereotypic stooges, suckers for anti-feminist normalcy.

Sadly, there will always be reasons not to transition, and there will always be people who think you shouldn’t—parents, peers, partners and politicians, to name a few. As a culture, we still don’t quite know how to make sense of the desire to change your body or sex outside of the vocabulary of medicalized monstrosity—except for cis people, who have greater freedom to modify their bodies without being made to account for themselves and their “identities.” If you are trans, though, this process is policed. It is harshly patrolled and endlessly examined. If you want to change your body, you must prove that you deserve to, and that means following a very specific script, where any deviation qualifies as freakishness.

Transition is often cast as a bogeyman. It is as though all our problems ought to be cured through “self-love” or “best practices” or “resistance,” vaguely defined. The idea that embodiment might factor into such an arrangement is off the table. These narratives stick; as a young trans person—and perhaps especially as a young non-binary person—transition felt like an impossible task, a political failure, a project that I was unprepared to take on. I didn’t know who or what I wanted to be, and information was hard to come by either way. Better to just avoid it entirely, said a voice in my head. This way, I can’t be disappointed.

I am glad I didn’t listen to it. But I imagine that such a voice is more common than many of us let on. I am often reminded of an excerpt from American writer Daniel M. Lavery’s new book, Something That May Shock and Discredit You, shared in The New Inquiry. In it, Lavery recounts a parodic but uncomfortably familiar monologue centred on a refusal to start hormones, or rather, to accept that he wants them. “It’s simple math, really: only trans people take hormones, and I’m not trans, because trans people are on hormones, and I’m not on hormones, so if I were to go on hormones it would likely cause some sort of paradox,” writes Lavery. “Of course if I had it to do all over again, I’d take them. Who wouldn’t? It would be the best thing imaginable for me. The trick is not to imagine it, and not to want anything.”

This is the scary part: Wanting to change your body, your sex, the way you move through the world, feels like an ugly thing to say aloud. Trans people, my friend, the poet Gwen Benaway, says, are not supposed to want things; we are supposed to be inspiring, glamorous, sympathetic, easy to work with. To want something, let alone to insist upon it, is ugly. It transforms you into a “trans activist,” someone with an “agenda,” a threat to children and women everywhere—chaotic, irrational.

But desire is an inextricable part of transness, and as selfish as it seems, there’s nothing inherently wrong with wanting your body to be a certain way. It doesn’t make you a sellout or an assimilationist or vain or petty; it makes you a human being. The difference is that there is a possibility of actually arriving at your destination. So I am suggesting, politely, that you consider it with kindness and seriousness: Be selfish. Do what you want.

“Desire is an inextricable part of transness, and as selfish as it seems, there’s nothing inherently wrong with wanting your body to be a certain way”

To be sure, hormone replacement therapy is not the ideal path for everyone. Hormones affect the human body in varied and complex ways, so some people fare better on them than others. In an ideal world, we could have these conversations freely and comfortably with informed medical professionals. But of course, transphobia makes this difficult; few doctors are competent when it comes to transgender healthcare. An ongoing history of gatekeeping in the medical field has also limited the vocabulary available to trans people in articulating what we want, how we feel and who we are. This is in part why certain narratives about what it “means” to be trans rise and fall in prominence over time—the most common (and commonly criticized) being the narrative of someone “born in the wrong body.”

None of this should be discounted; there are real barriers that prevent our access not only to transition but also to essential knowledge about what it means and how it works. Narratives about transition, however, are not the same as transition itself, and just because gender is often imagined as binary doesn’t mean yours has to be. You don’t have to medically transition in order to “be” trans (whatever that means), and there are countless ways to live and express yourself outside of hormones or surgery. You are not wrong for not being interested in transition, and your choice to pursue it or not pursue it does not in itself make you any more or less trans than anyone else. All that said, though, I believe that there is a reason why so many trans people do choose to medically transition, and why those who love us and hate us see it as central in the fight for our status in society. Hormones don’t make you trans, but they are important tools available to you in actualizing yourself, on your own terms, in your own body.

That’s the point of transitioning, the anxiety and the joy of it: Becoming yourself. Writing about their transitions, writer and scholar Esther Nikbin describes their discomfort with the stereotypical hyper-femininity often projected onto trans women, and their personal satisfaction with butch androgyny. “I realized I didn’t want the after of a conventionally successful timeline; I wanted myself, a later I could only find by constructing it on my own,” they write. “I would never be the girl pulled out of the hat in a brilliant white wedding dress, and that was okay, because I no longer wanted to be.”

“You don’t have to have all the answers. The point is to give yourself permission to experiment”

Figuring out what it means to live in a gendered body and navigating that embodiment is an ongoing process. I will never be comfortable being perceived as a man. Understanding myself as non-binary and as a woman has been helpful in articulating what I want and with whom I am in community, even if the words we use to describe ourselves aren’t always the same. But I know that however I present and however I explain my identity, I am in good company. The trans women and non-binary people I know, from whom I’ve drawn strength and support, are complex people with similarly complex ways of actualizing their ideal selves. Many of them have changed their hormone regimens, styles of dress, preferred pronouns, identity labels and even their physical anatomy to fit their evolving relationships with gender and sexuality.

In time, I am sure that I will as well. All of this is part of my journey, and I am no longer afraid of its uncertainty. It is incredibly, almost boringly normal to not know exactly what you want to do and who you want to be. You don’t have to have all the answers. The point is to give yourself permission to experiment. Everything, absolutely everything, is a phase. Instead of running from this fact, I want you to try embracing it. Your body is a work in progress, and it is yours every step of the way. Go ahead, transition.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra