A fire eater at a prison sexual health rally Credit: Aaron Leaf

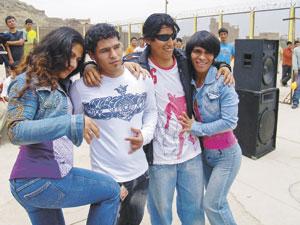

Sexual health volunteer Edber Pisango, left, and his friends outside an Iquitos nightclub. Credit: Aaron Leaf

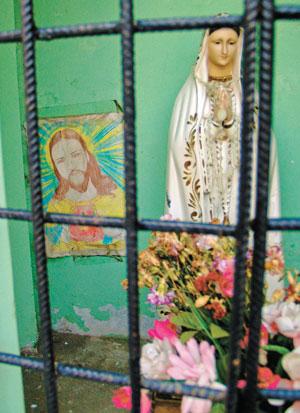

A shrine outside the Lurigancho prison HIV clinic. Credit: Aaron Leaf

The Lurigancho prison dance team. Credit: Aaron Leaf

Peruvian human rights activist Taki Robles is late for our meeting in the Lima suburb of Miraflores. I chalk it up to Lima’s formidable rush hour, which lasts until well past sundown, but as I learn later, that’s not the case.

Robles had been looking for a cab. When one finally stopped and Robles got in, the driver told her, “Sorry, but I was confused.”

“Why? I need a ride,” Robles said.

“No, I thought you were one of your friends offering me services.”

In Peru, says Robles, who is transitioning from male to female, being trans is so closely associated with sex work it is a constant struggle just to get around.

By her estimation, 90 percent of the trans community in Peru are sex workers. “Not because we want to do it,” she stresses, “but because we have to, to survive.” Consequently, her work to improve the lot of Peru’s trans community is about promoting economic independence, improving access to healthcare and building self-esteem among her peers. Ending discrimination, she believes, relies on all these things.

Robles, who is HIV-positive, is tall with long black hair and an energy befitting her reputation as a tireless organizer. It’s hard to believe that just six years ago she was on death’s door, weighing 35 kilograms and with a CD4 protein count of seven (a person without the virus, by comparison, might have around 800). Her first organization, Friends Forever, was formed 12 years ago, after she was diagnosed with HIV. At the time she didn’t know much about the disease other than that it was deadly and that the drugs to fight it cause horrific side effects.

“I had lots of questions and no answers, so I started looking for info and realized I wasn’t the only one. There were many of us that had the same problem, but we didn’t have the means to communicate,” Robles says. Low literacy levels and social isolation can hinder access to information, and her group, formed initially for emotional support, became an important tool for sharing knowledge.

At the time, access to drugs was difficult. It was as she fought to get treatment, while watching close friends die, that Robles had an awakening about human rights. “Because we already live excluded, we should not exclude ourselves,” she says. When the community is forced underground even things like homemade breast implants become life threatening. She’s been lobbying the government to go beyond ending anti-trans discrimination in healthcare and to enforce Peruvian law that says the state is “required to provide integral care (including treatment) to all people living with HIV/AIDS.”

At 0.4 percent, Peru has an HIV rate roughly equivalent to Canada’s, but among men who have sex with men the prevalence is 13.7 percent and rising, accounting for more than 55 percent of total incidences of the infection. Among trans sex workers, the prevalence rockets to an estimated rate between 32 and 45 percent. Combating HIV in Peru is, at its core, about reaching out to populations on the margin.

In her outreach, Robles has found that many in the trans community avoid public transportation because of fear of discrimination. The result, says Robles, is that they don’t move around much.

“There’s no social life because you don’t go out, so you just generate your own spaces and your own groups. So we started trying to locate these groups so we could reach out.” There are now eight committees in the Lima region. Through them, her organization distributes information about health and human rights.

On Nov 12, she opened a community centre dedicated to the trans community: “I want to give my colleagues the space where they can find information but also say what they think and feel, not only creating an association but an ideology of change.” Change, Robles believes, is about building self-esteem and fostering personal responsibility. “You have to go to the hospital,” she tells her members. “If you don’t go to the hospital because you think you will be discriminated against, it’s also your fault.”

Her work lobbying the Ministry of Health landed her a role in Peru’s Country Coordinating Mechanism, a body designed to assign funding from the Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria to the groups that need it. The Global Fund has funnelled more than $62 million toward fighting AIDS in Peru since 2003. Robles’ role is to make sure vulnerable communities don’t get left out of the funding.

***

Before landing in Peru I had imagined it as a tradition-bound Catholic country full of swaggering machismo. But my first week there I formed a more complex picture. Without going out of my way, I was meeting trans people on a daily basis. From Merilyn, a tuberculosis survivor who volunteers with the non-governmental organization Prisma, training tuberculosis sufferers in sustainable farming, to trans prisoners at Lurigancho prison, dancing to raise awareness about sexual health.

It seemed to me, at first glance, that trans people are part of Peruvian society in a way that one doesn’t see in many countries, including Canada. The most striking example is a popular TV host, a larger-than-life drag queen in billowing peasant dresses named La Chola Chabuca who has a dedicated following among indigenous Peruvians. But Robles tells me that this openness is deceiving and that on a larger level these issues are not discussed. For example, the man who plays La Chola Chabuca, Ernesto Pimentel, despite being open about his HIV status “hasn’t come out to say he’s trans. She’s just a character on TV. It’s a commercial character constructed for TV and not a real transsexual.” There are other characters on Peruvian TV, says Robles, that are far more vicious, “using transvestites to portray us as freaky and stupid.”

***

Flying into Iquitos is a reminder that Peru is covered in vast tropical forests. Up to 60 percent of the country lies east of the Andes in the Amazonian region. In this bustling regional city is an exuberant and open queer community with a handful of clubs and an open trans population. It feels worlds away from dour, pollution-choked Lima.

In front of A Chelear nightclub, people are preparing for a night of partying. A parked car blasts bass-heavy cumbia, and across the street people sit at plastic tables drinking Cusquena beer in the warm night air. I meet Celeste Torres and Edber Pisango, volunteers with the organization Selva Amazónica, who are gearing up for a night of sexual-health awareness-raising in and around Iquitos’ queer party spots.

Torres, who is trans, credits the open and tolerant atmosphere in Iquitos to the hard human rights work the community has done over the years.

“In Lima you have very specialized groups: you have lesbians on one side; you have men who have sex with men; you have trans. Here we all come together. We organize ourselves and we work on the issues together. That’s what makes us different from Lima.”

According to Pisango, who is gay, the queer community in Iquitos is remarkably integrated. There are numerous queer-friendly bars and clubs spread throughout different neighbourhoods, and people he knows stay close to their families. “The Catholic church,” he says, “is never going to share the ideas that we have. That’s not going to change.” He, however, attends church regularly and has never been excluded from practising his religion.

The two chat and joke around with patrons outside the bar, but when it comes to discussing health they get serious. The patrons seem to take it seriously, too, eagerly asking questions and taking free condoms. Later, our mototaxi driver, who we hired in front of the hotel, gets his own private session with Torres.

“Five years ago before we had these programs,” says Torres, “I had many friends who died. Gays and transvestites now go and get tested. Yes, there is progress.” But for all this feeling of inclusion, says Pisango, they have a hard time reaching lesbians. “In Iquitos, lesbians aren’t visible,” he says. “We invite them . . . but they’re ashamed. They don’t come out. It’s a very small minority that attends meetings.”

***

Back in Lima, in Lurigancho, Peru’s largest and most notorious prison, I tour a new clinic where tuberculosis patients give testimonials about their recoveries. I lag behind the group. A brass band marches past. I follow a man carrying dozens of balloons, and suddenly I’m in a football-field-sized prison yard surrounded by thousands of prisoners and talking to a giant penis. His name is José Luis and he is in the prison yard to raise awareness about spreading HIV and other sexual infections. The bottom half of his penis costume is decorated with hand-painted illustrations of infected genitalia.

HIV, he says, is spread in prison through syringes and shaving. When I press him, he admits, “Yes, sex too. Sometimes female prostitutes are allowed in here.”

And men having sex with men?

He admits, “That’s very common, too.”

He tells me there’s no discrimination against inmates who have sex with each other. HIV-positive people, however, are “segregated” to prevent the spread of the disease.

That’s a misconception, says prison doctor José Best Romero. There’s a clinic where people with HIV go to get medical attention, but it’s not segregation. Once a prisoner is getting treatment he is released back into the chaos of the general population. The HIV infection rate in Lurigancho is 2.7 percent. Of those, 17 percent also develop TB.

“[I] cannot deny there’s a lot of sex going on,” says Best Romero.

But information is hard to gather. The statistics available state that when there is intercourse, inmates will use a condom 33 percent of the time. That’s a huge step up from years past when there were no condoms in prison.

It’s a political issue, he says. The church puts a lot of pressure on authorities not to invest in condoms. “They’re delivering condoms to criminals” is the message.

Back in the yard, a prisoner dance team is giving a reggaeton-backed performance of hip-hop dancing. Two trans prisoners are grinding suggestively with their partners and breaking away into synchronized booty shaking. The crowd loves it. The prisoners are eventually shepherded inside for blood tests.

***

Ten days is too short a time for an outsider to really understand the forces that shape a community, but it does give context to one’s own culture. Besides gaining a new awareness of how invisible trans issues are in Canada, meeting Taki Robles was an experience that made me reevaluate what it means to fight for something.

For both Robles and the activists in Iquitos, there’s a clear correlation between the work they’ve put in and the progress they’ve made. And when the mission is so personal, success as an activist is closely linked to personal growth. Almost everyone I spoke with told me how their work has affected their own lives in transformative ways.

Robles has, for years, been pressured to leave for a more comfortable life outside Peru. Her family emigrated long ago and have been encouraging her to follow. It would mean stability and better access to sexual reassignment surgery. “This would be easy,” she says, “but I can’t leave here only to abandon everything I’ve done, and everything I need to do still. My community needs me.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra